Our epilogue follows the lives and fates of the various “players” in the Arbuckle case. There are a few happy endings. Zey Prevost got married and lived an uneventful life. But most are rather tragic. Alice Blake died in a car wreck. Al Semnacher’s career was effectively over and he died of a heart attack a year after the trial. He was followed by Rappe’s “Uncle Joe” Hardebeck, who locked himself in his bathroom and shot himself. Maude Delmont lived as a recluse in Southern California under her maiden name. And so on.

There is almost an Arbuckle curse. But most of the epilogue is a survey of Arbuckle’s life after he was acquitted and it begins with this novel way of looking at the abortive attempt to reinstate the comedian and an “exposé” that was very much believable in regard to Arbuckle’s conduct.

Most books about the Arbuckle case—and those that devote chapters to it, like William J. Mann’s Tinseltown—seem to treat the resistance to Arbuckle’ return with disdain, as if they were nothing but “church ladies” to use Mann’s term for a very diverse group of women. Such writers assume that the majority of Americans wanted to see Arbuckle on screen again. What is more evident is that they didn’t care. They didn’t miss him. And one has to consider, in all fairness, that letting Arbuckle out of his box required real denial.

On December 20, 1922, Will H. Hays, while in Los Angeles, issued a statement in the Yuletide spirit. He intended to pardon the comedian, reinstate him as a film actor, and eventually lift the ban on his films. Arbuckle welcomed the news and expressed his gratitude. Naturally, he felt he deserved such Christian charity and, as yet, no one had noticed that for all those weeks and months since September 1921, no one observed him “darken the door” of any congregation. He had long ago maintained the separation of church and stage.

The blowback from clergymen was swift. They felt Hays should have consulted them. The Women’s Club of Hollywood, the National Committee for Better Films and the National Federation of Women’s Clubs demanded that Hays to take his Christmas gift back. The Rev. Dr. Wilbur Crafts surely knew of this outrage. But his voice was silenced by his untimely death “after a shockingly brief illness,” according to one Washington newspaper mourning his loss to the cause of the suppression of immorality.

The mayor of Los Angeles, who understood the lingering “disgust” for the debauchery revealed in People vs. Arbuckle, telegrammed Hays as he distanced himself from the controversy, en route to his home in Sullivan, Indiana. By the time he arrived, he had stacks of such wires from other mayors and every kind of prominent citizen. He now had to deal with the fact that Arbuckle’s innocence was never wholly accepted in Hollywood and his preexisting reputation never went away, even in the film colony, many of whom saw the comedian as liability.

Indeed, Hays proved to be remarkably tone-deaf to the real situation, made all the more real by the inopportune federal indictment in Los Angeles of one Ed Roberts a few days before Hays arrived on December 13, waxing with bonhomie and compassion for such artists as Wallace Reid and Roscoe Arbuckle.

Roberts, who managed such two film magazines, it and the Motion Picture Magazine of Joy, was also a spokesperson for the Affiliated Motion Picture Interests. This organization, which included the late William Desmond Taylor on its board, represented not only producers but rank-and-file actors, workers, and other employees of the motion picture industry and flourished until it ceded its mission—to disassociate its members from the industry’s black sheep—to Hays and the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America. Roberts was also a political activist in Los Angeles. He headed the Tenants Protective Association and sought the arrest of landlords whom he considered “rent-profiteers” and backed a citywide rent strike. He also organized the resistance to evict the so-called “squatter” families on Terminal Island and ran an unsuccessful campaign for city council on platform against blue laws and censorship. In other words, he wasn’t afraid of being controversial or contradictory.

Before the third Arbuckle trial began in March and before Hays took the reins of the MPPDA, Roberts put the finishing touches on The Sins of Hollywood, an eighty-page pamphlet published anonymously in May. In his introduction, piquantly dated April 1, 1922, Roberts stated, “Eight months before the crash that culminated in the Arbuckle cataclysm, they knew the kind of parties Roscoe was giving—and some of them were glad to participate in them—”

In October 1921, weeks before the first Arbuckle trial, Matthew Brady had come to Los Angeles on a fact-finding mission to learn first-hand about such gatherings. That he may have spoken to Roberts or those who could vouch for his veracity is unknown. But ultimately Brady agreed with Gavin McNab not to resort to such character defamation and thus tied a hand behind the prosecution’s back.

Copies of The Sins of Hollywood were scarce and it never saw anything like a national distribution. Even so, a deputy U.S. attorney in Los Angeles branded the book as “scurrilous” and the city’s chief post office inspector promised to ban the book from the mails as well as find and prosecute the author. In any event, someone with influence, someone in the motion picture industry, saw the book, saw that it sent the wrong message with Will Hays in place, and complained—perhaps all the way up to Hays himself.

Roberts was hardly graphic. But he was a good writer and knew how to be shamelessly suggestive in describing the party and sex subculture of Hollywood. His real offense was that he made it very easy to guess the names of the actors and actresses whose names he barely disguised along with their transgressions. “Jack” was Mack Sennett. “Molly” was Mabel Normand. The 1916 love triangle between her, Sennett, and Mae Busch and the “battle royale” between the two actresses wasn’t hard to miss. “Walter,” the dope fiend, was Wallace Reid. “Adolpho” was obviously Rudolph Valentino and “Rostrand” was Roscoe Arbuckle.

Recall that Virginia Rappe said, before she took the elevator up to twelfth floor of the St. Francis Hotel, that she hoped Arbuckle’s party wasn’t a “bloomer”—a disappointment. Did she expect something like the following entertainment, the arousal, the bad taste? “Not so long ago a certain popular young actress returned from a trip,” Roberts began.

She had been away for ten days. Her friends felt that their ought to be a special welcome awaiting her. Rostrand, a famous comedian; decided to stage another of his unusual affairs. He rented ten rooms on the top floor of a large exclusive hotel and only guests who had the proper invitations were admitted.

After all of the guests—male and female—were seated, a female dog was led out into the middle of the largest room. Then a male dog was brought in. A dignified man in clerical garb stepped forward and with all due solemnity performed a marriage ceremony for the dogs.

It was a decided hit. The guests laughed and applauded heartily and the comedian was called a genius. Which fact pleased him immensely. But the “best” was yet to come.

The dogs were unleashed. There before the assembled and unblushing young girls and their male escorts was enacted an unspeakable scene. Even truth cannot justify the publication of such details. (p. 74)

In late July, Hays traveled to Los Angeles and couldn’t avoid The Sins of Hollywood, with its lurid red Mephistopheles and his camera on a startled flapper and her beau. A respected Los Angeles minister handed him a copy at the behest of the author. Hays was appalled but he didn’t change his message before an enormous crowd that filled the new Hollywood Bowl. Hays had cover for the motion picture industry and declared, “The one bad influence in Hollywood is talk. And for the life of me I cannot see the horrors of Hollywood.”

In mid-December, Ed Roberts was finally identified as the author and indicted by a federal grand jury for having distributed over 10,000 copies of The Sins of Hollywood. For Hays, who only wanted to play Santa Clause for Arbuckle, an overzealous federal prosecutor had, perhaps, presented him with a very inopportune gift, ill-timed given the Arbuckle pardon. Indeed, the ministers and clubwomen who swore by Roberts would want Hays to act more like a moral policeman.

In the end, two of the latter put up the bail of $5,000—and Roberts said that he could name names and substantiate every one of his salacious claims, such that federal investigators wanted his cooperation in busting a dope ring. With the new year, Robert’ trial was postponed and eventually disappeared from the federal docket.

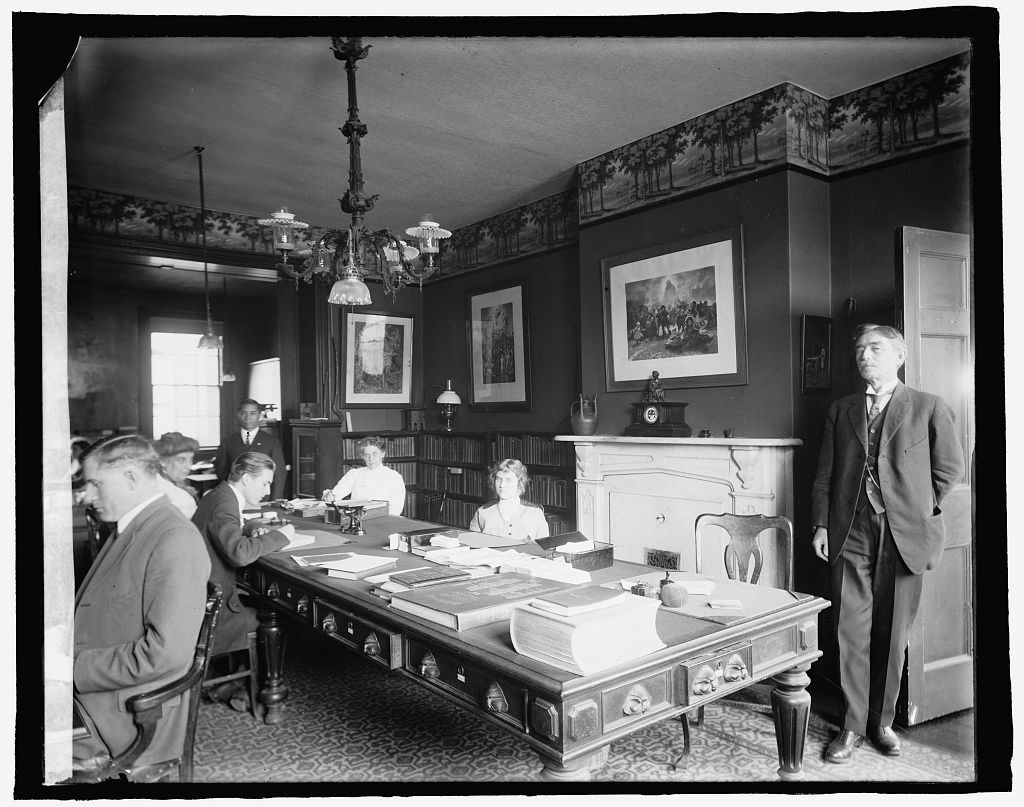

The Rev. Dr. Crafts and the staff of the International Reform Bureau. The African American man in the background ran the organization’s printing press. (Library of Congress)

The Rev. Dr. Crafts and the staff of the International Reform Bureau. The African American man in the background ran the organization’s printing press. (Library of Congress)