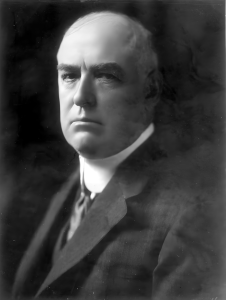

In defending the indefensible, so to speak, a plausible explanation had to be invented for Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle’s wearing silk pajamas and a purple bathrobe as he greeted female guests in his suite at the St. Francis Hotel on Labor Day 1921. After all, two assistant district attorneys, in their closing arguments for convicting Arbuckle of manslaughter in the death of Virginia Rappe, had made a special point of making the comedian out to be so debauched, so louche, in still wearing his pajamas after emerging from room 1219 with the fatally injured actress lying on a bed saturated with his perspiration. And for those with less than a longer memory, the journalist Adela Rogers St. John in “Love Confession of a Fat Man,” a feature interview published in the September 1921 issue of Photoplay, devoted some ink to the same or similar pajamas that Arbuckle wore in her presence at the same time of day.

We were lunching together in his bedroom. I shall never be able to estimate just what percentage of effect they had on me—those pongee pajamas. Of course, I had seen men in pajamas before. If you read the ads in the magazines you can’t help but see men in and out of most anything. But I’d never interviewed in them before. And I love pongee pajamas. I suppose it is only fair to my husband to state that the bedroom was a set—on stage three, at the Lasky studio. That the pajamas and the dressing gown and even the bath slippers were only his costume for a scene and that we were almost aggressively chaperoned by seventeen stage carpenters, thirteen electricians, a few stray cameramen, and a troop of studio cats. And Oscar. The colored gentleman that “tends to” Mr. Arbuckle.

Nevertheless, those pongee pajamas were exceedingly—intrigante, if you understand French. That is to say, one really can’t talk to a man in his pajamas without feeling more or less—well, sympathetic and well-acquainted, so I may have taken too lenient a view of his view for a confessor.[1]

The interview is strange in that Arbuckle is not single but rather married. And the interview is conducted in a bedroom. That is even stranger, for it required that Mrs. St. John make up an excuse for the pajamas by saying that the comedian had just been working in front of the camera, which, of course, invites the question: Did Arbuckle’s contract provide for a bedroom rather than a dressing room attached to the set? In any event, he did wear such a costume in Leap Year, the last Arbuckle vehicle to be filmed in the late summer of 1921. He would not make another comedy until a decade later.

That said, the same excuse could not be made for the Labor Day debauch. It took another motion picture magazine piece to explain away the pajamas and bathrobe, this time attributed to the wife who goes unmentioned in the love confessions, Minta Durfee, assisted by Paramount’s publicity department and Arbuckle’s lawyers.

“Not long before the trip to San Francisco, Mr. Arbuckle was accidentally burned with muriatic acid,” Minta disclosed in Movie Weekly in late December 1921, three weeks after the end of the first trial and as many weeks before the start of the second.[2] The injury required that Arbuckle wear thick cotton dressing, which naturally, conflicted with his vanity.

He always had his clothing made rather tightly fitting in order to keep him from looking any fatter than he is, and tight clothing over the burn was anything but comfortable. Whenever he could, he wore loose clothing, and that was why he was dressed in pajamas on the day of the party.[3]

This excuse, or rather alibi, was then put to good use at the second trial. During the cross-examination of two prosecution witnesses, Zey Prevost and Alice Blake, Arbuckle’s chief counsel Gavin McNab made a special point of asking each one if Arbuckle had asked them if he did not request their pardon for being dressed the way he was during the early afternoon of September 5.

Q. Miss Blake, did Mr. Arbuckle make any explanation to you about his reason for receiving young ladies in his room in his dressing gown and pajamas? A. Why, I believe he did mention it, he said something about a burn or something.

Q. What? A. He said something about a burn.

Q. Did he apologize to all of you young ladies and say that the reason that he had to receive you in that way was that he had had a serious accident. A. Yes, sir.

Q. And that he could not be comfortable otherwise than this gown? A. Yes, sir.[4]

Assistant District Attorney Leo Friedman objected on the ground that “this is a collateral matter” and hearsay—and he likely knew better. And there would be no doubt after the long and contentious testimony of Zey Prevost, whose memory failed to the point at which the prosecution wanted to the court to declare her a hostile witness. As Friedman’s colleague, Milton U’Ren pointed out, “She had been under other influences since the last trial.”[5]

When it was Zey’s turn to vouch for Arbuckle’s excuse, Friedman objected once more “on the right of counsel to broach brand new matters in a leading and suggestive manner.”[6] And argument took place over several pages before Zey could answer as desired that Arbuckle made apologies, “that he was sitting in some acid, or something, in a machine [i.e., an automobile], and burned himself, and that he was more comfortable in his pajamas and bathrobe, than he was in his clothes.”[7] What followed, however, was another line of questions that is why we want to close read what Friedman called “a hullaballoo over nothing.”

Q. Miss Prevost, you have had no conversations with counsel for the defense since the district attorney first saw you in the other case, or with any of the defense counsel up to this time, have you? A. No, sir.

[. . .]

Q. You are not under the influence or duress of anybody? A. No, sir.[8]

Of course, while the prosecution could no longer keep Misses Blake and Prevost incommunicado as they had done before the first trial—because they could not be trusted—they had surely been tailed by police detectives and that both women had made contact with Arbuckle’s lawyers and knew what to say so as not to perjure themselves and to no longer be effective witnesses for the prosecution of the comedian.

[1] Adela Rogers St. John, “Love Confessions of a Fat Man,” Photo Play, September 1921, 22.

[2] The excuse seemed to resonate with another—and quite plausible one—for the carbuncle he suffered for months in 1916–’17. Rather than having it treated, he let if fester and relied on morphine injections—and very likely heroin—to dull the pain. The comedian was negotiating and ultimately signing a contract with Paramount Pictures and he could ill afford to be hors de combat—out of action. By the time he arrived in New Yor City in March 1917 for a series of dinners marking his million-dollar deal with Paramount, Arbuckle was on crutches and could barely walk without assistance.

[3] Minta Durfee, “The True Story about My Husband,” Movie Weekly, December 24, 1921.

[4] People vs. Arbuckle, Second Trial, “Testimony of Alice Blake,” p. 882.

[5] Ibid., “Testimony of Zey Prevost, p. 1023.

[6] Ibid., p. 1032.

[7] Ibid., p. 1036.

[8] Ibid., pp. 1036, 1037.