The following passage is from our work-in-progress. It is a preamble to a section titled “Fatty’s in Town” and introduces a person—a caricature really—found in William J. Mann’s bestselling Tinseltown (2014), an entertaining book about the unsolved murder of the actor and director William Desmond Taylor, which occurred two days before the second Arbuckle trial ended in a hung jury. Although Mann misidentifies the Rev. Dr. Wilbur Crafts as the leader of the Lord’s Day Alliance—who, for the record, was Rev. Harry L. Bowlby—Crafts did play a role in the crusade to regulate motion picture content.

In 1895, Crafts and his wife, Sara Jane Crafts, founded the International Reform Bureau in Washington, D.C. as a platform from which to lobby on behalf of Christian values. Over the years, they were primarily concerned with temperance, though also campaigned against smoking, gambling, drugs, divorce, and the Ku Klux Klan. They also lobbied for suffrage and the education of children. Late in his career, after the 21st Amendment (Prohibition) was passed, Dr. Crafts turned his attention to Hollywood.

Mann describes Crafts as Adolph Zukor’s bête noire. That designation gives Crafts too much credit, Zukor, the president of Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount, the biggest studio in Hollywood, wasn’t so easily intimidated, and this self-appointed crusader didn’t have the political muscle to force a change. Crafts’s campaigns against Hollywood did make the news though and Zukor didn’t ignore the message. He sensed that a change would soon be needed to protect the industry from government interference.

Rev. Dr. Wilbur F. Crafts (Library of Congress)

Fatty’s in Town

The Rev. Dr. Wilbur Fisk Crafts, superintendent of the International Reform Bureau, virtually anticipated the arrival of Virginia Rappe and Roscoe Arbuckle. The great man went to San Francisco for its lifestyle and to save people like themselves from themselves.

Dr. Crafts was the veteran of many hard campaigns to establish blue laws throughout the United States and the Volstead Act. Indeed, the old gentleman with his trim gray beard and mustache considered Prohibition a lifetime achievement. Then he embarked on a renewed campaign—to regulate the offensive content of motion pictures, including the posters outside theaters.

Such activism brought in the donations that funded the Reform Bureau and Dr. Crafts now had the time to take on the motion picture industry in earnest. In 1916 he had lobbied the House Committee on Education for a federal censorship of motion pictures. But Mutual and other studios had better lobbyists and Wilbur was frustrated. He also wanted to ban newsreels of boxing matches, not only for their violence but the way they incited race hatred when the bout was between Jack Johnson and a white boxer. Then, between Thanksgiving and Christmas 1920—and in recognition of the tercentennial of the Mayflower landing—the man of faith forced himself to attend one motion picture after another in the theaters of Washington, D.C. and came away appalled by the “criminal and vicious tendencies” he witnessed firsthand, and the “sex thrill” taking the place of the “alcoholic kick.”

The depictions of women and their effect on young people were particularly offensive. “I would rather have my son stand at a bar,” he said, “and drink two glasses of beer than have him see the vampire woman that I saw. He may get over the effects of the beer in a week, but he could not forget that vampire woman until he was eighty years old.”

Dr. Crafts promised to rescue “rescue the motion pictures from the Devil and 500 un-Chrisitan Jews.” Then he came to many of the latter in the motion picture capital of the world, Los Angeles, in April 1921. There, he would speak to studio executives about the need “to reform and uplift the character of film productions” and to sell his idea of an interstate motion picture commission, which entailed hiring devoted men and women like himself. But he only met with one producer, Benjamin B. Hampton, whose westerns didn’t have any vamps. Then Crafts boarded a train for San Francisco.

He had two objectives. First, to protest the showing of a new film, Fate (1921). Its ingenue star, Clara Smith Hamon, was seen as exploiting the story of her life as the teenage mistress of the late Jake Hamon, the Oklahoma oilman—and friend of President Warren Harding—whom she had killed in self-defense, a plea her lawyers cleverly used to beat a murder charge. Second, Dr. Crafts intended to establish a branch of the Anti-Saloon League in the “wickedest and wettest” city in the nation and launch a campaign to “clean up” San Francisco to be launched in the fall of 1921. And here Dr. Crafts met his real match—modern women—a “pernicious evil.”

“Women of today have only two objects in life,” he said to the San Francisco Examiner,

to vamp and be vamped. We intend to change that [. . .] The only way to keep the girls of today straight is to make them fear the consequences of wrongdoing. There is no such thing as a prodigal daughter, and there shouldn’t be.

He went on. A certain leniency toward the “fallen woman” was not just a grave mistake, it was criminal. Crafts didn’t like “movie queens,” the “chic” and “baby doll” type on the cover of so many magazines and now everywhere in every American city. He preferred the pert breasts and arm freedom of the Venus de Milo—this even though the man of the cloth a month earlier decried a nude statue by Charles Cary Ramsey in New York for not being draped enough). But many clubwomen were no less appalled by his obvious misogyny and the mischaracterization of their city.

“Contempt is the proper spirit in which to treat such utterances as Crafts is quote as making,” said Mrs. Frank G. Laws, president of the California Civic League. Mrs. Carrie Hoyt, a Berkeley feminist and political worker, was more vocal. I think it is a crime for a man to make such statements as he is quoted as saying,” she said in the Oakland Tribune.

What he needs is a deputation of California women to demonstrate to him that they neither have time nor inclination to “vamp or be vamped.” He needs to be shown what manner of women we of the west are. [. . .] A man has no right to come and advertise to the world that San Francisco is the wickedest city of the nation. We are not so wicked as many other cities. What vice we have is not hid. Our women may go anywhere they please and if the go right, they are not insulted.

There was no deputation. Dr. Crafts initiative against motion pictures, pretty young women, and San Francisco faded away. The Zeitgeist that made the city such an attractive destination for sinners, especially the sinners of the film colony in Los Angeles, who opened their arms to him, or so he thought, were glad to see their gadfly gone. Dr. Crafts spoiled no one’s fun for the time being and the prodigal daughters of San Francisco awaited.

* * *

Arbuckle and his companions, the director Fred Fishback and the actor Lowell Sherman, set out from Los Angeles on Friday, September 2, [to be continued ]

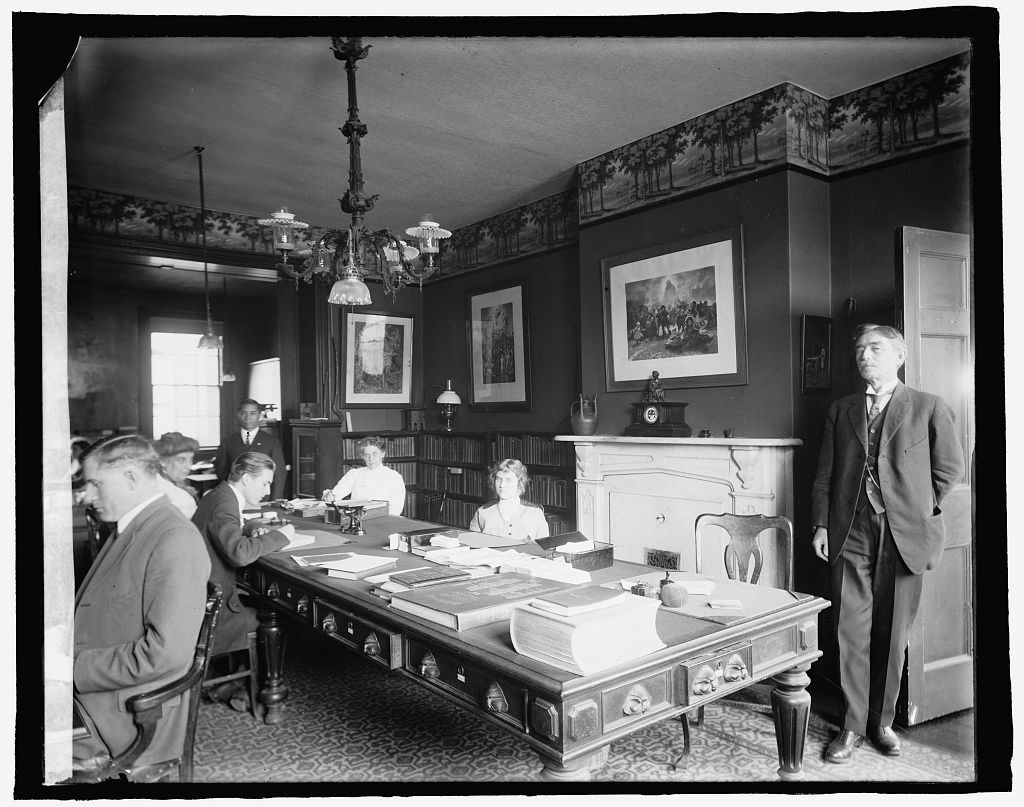

The Rev. Dr. Crafts and the staff of the International Reform Bureau. The African American man in the background ran the organization’s printing press. (Library of Congress)

The Rev. Dr. Crafts and the staff of the International Reform Bureau. The African American man in the background ran the organization’s printing press. (Library of Congress)