The narrative of the second trial will not have the same blow-by-blow detail as the first in Spite Work. The second trial, which could be called the “medical trial,” saw more emphasis on the medical expert evidence (rather than the “moral” evidence of the third), for both sides had more time to digest the report of the court-appointed committee of three pathologists who examined specimens taken from Virginia Rappe’s preserved bladder under a microscope. This is why the second trial begins with the testimony of those physicians. They found no pathological cause for a reptured bladder. They did find chronic cystitis at its base (i.e., the trigone region). Technically, legally, the bladder was “diseased,” but not in any that could have contributed to a rupture, spontaneous or with the application of external force. The three pathologists testified one after the other on at the second trial. They were followed by Dr. Arthur Beardslee, the St. Francis Hotel physician discussed in an earlier blog, who treated Virginia and was the first to suspect that her bladder had ruptured. His testimony at the preliminary investigation and the first trial surely fascinated jurors because there was the remote chance that she might have been saved. They also had to wonder just what kind of people were making decisions for her welfare that prevented timely, even heroic surgery. One might think her death was a group effort.

During the second trial, Dr. Beardslee had to explain once more a term that only he used, “surgical abdomen.” That is, prompt surgical intervention to treat underlying pathologies such as infections, perforations, as well as obstructions. He reasoned that

The symptoms and signs were those of a—that referred to the bladder, and as I said, were classical of a ruptured bladder. The only—one thought would be to get a case like that to the hospital, to get it into the operating room, and open the abdomen, and sew up the bladder or do whatever was necessary.[1]

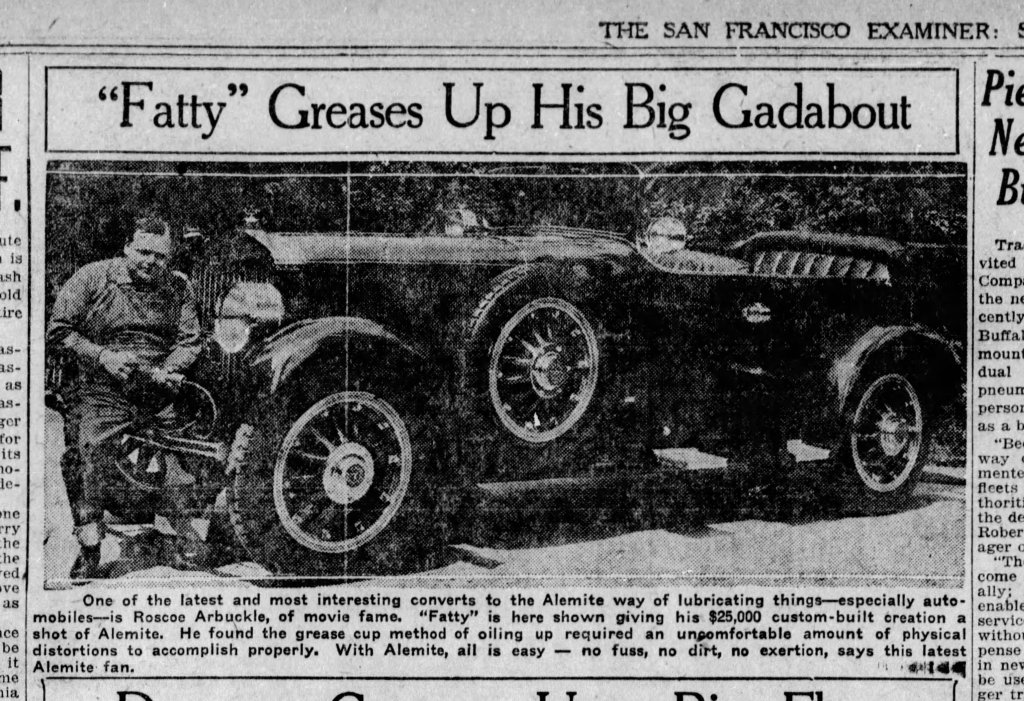

As the lawyers led Dr. Beardslee through his examination and cross-examination, he was not allowed to repeat conversations with Virginia, her companion Maude Delmont, or the “people,” on the twelfth floor of the hotel, who undoubtedly were informed that surgery was a real opition. “Whatever was necessary,” however, risked notoriety, police, reporters. Those people, who would have included Roscoe Arbuckle, the actor Lowell Sherman, the comedy director Fred Fishback, and the person who became the comedian’s minder during the Labor Day party, Mae Taube (Bebe Daniels’ bestie for lack of a better designation), all of them, likely had a say. They all surely ignored Dr. Beardslee’s suggestion.

Gavin McNab

We can only guess what the hotel physician said through Mrs. Delmont, who acted as an intermediary between rooms 1227 and 1220. Dr. Beardslee’s delivery likely lacked any melodramatic urgency. A certan deference was afforded to celebrity guests as well as discretion. Arbuckle’s lawyers, however, wanted to hear about another conversation that Dr. Beardslee heard. Gavin McNab, the comedian’s lead counsel, made an impassioned speech about being allowed to cross-examine Beardslee on this point as an offer of proof. As you read the following, there is no mystery in his delivery. McNab had a pronounced Highland accent that tended to leave jurors and reporters awestruck in 1921.

If the court please, as part of the very history of this case, this witness, the State’s witness, the medical assistant sent for this young girl in distress, he calls there, under the most solemn and sacred circumstances, under circumstances in which she would reveal to him, or this person for her, in her presence, would reveal her condition, and this being necessary question to the history of the case, did she ask her if anybody injured her, so he himself therefore could apply the remedies that would cure this girl; that was, under these solemn circumstances, the heart of the case, the history of the case; it was one of the most solemn pieces of testimony, one of the most direct pieces of testimony, and one of the most convincing pieces of testimony, the statement of the girl herself, or somebody for her, given at that time, which can be presented to this jury.[2]

The rhetorical investment here is impressive and served a purpose: to get Arbuckle acquitted as cleanly and efficiently as possible. This was a trump card flashed early and the prosecutors knew the reason. Their witness, Dr. Beardslee, had been compromised into saying that he had asked Virginia Rappe directly and to the effect, “Did someone hurt you?” This would have destroyed the case against Arbuckle then and there. To obviate McNab’s offer of proof, the prosecutors objected on the grounds that “hearing from the girl herself” would be hearsay. But if McNab wanted to present such a conversation, he could resort to calling Mrs. Delmont to the stand. She was not a State’s witness. The prosecutors deliberately kept her off the witness stand, save for the earliest venues (the Grand Jury, the Coroner’s Jury). Spite Work examines the reasons for doing so, even though Mrs. Delmont signed the murder complaint against Arbuckle. Let’s just say for now that she would have added a certain complexity to the case that would cause both sides a lot of problems, like exposing the conversations Dr. Beardslee had with Arbuckle and his people through the woman in the middle. The evidence, which any jury, whether now or a century ago, would have to be struggled through to arrive on a verdict. So the K.I.S.S. principle of case design had to be employed.

In any event, the prosecutors defused McNab’s offer by reminding him that Mrs. Delmont was “available to him.”

[1] People vs. Arbuckle, Second Trial, “Testimony of Dr. Arthur Beardslee,” p. 793.

[2] Ibid., 799.

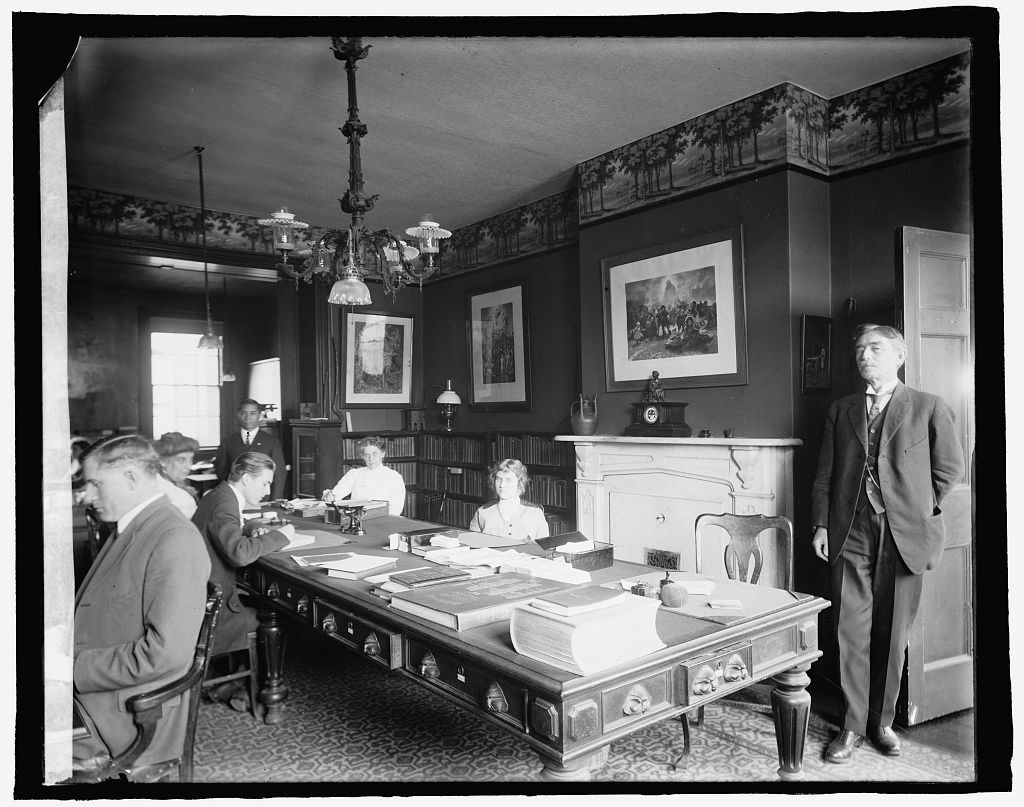

The Rev. Dr. Crafts and the staff of the International Reform Bureau. The African American man in the background ran the organization’s printing press. (Library of Congress)

The Rev. Dr. Crafts and the staff of the International Reform Bureau. The African American man in the background ran the organization’s printing press. (Library of Congress)