Al Semnacher’s inland route north took the recently completed California Highway 4, the precursor of U.S. Route 99 and present-day Interstate 5. By the late summer of 1921, the road was concrete-paved and designed for the top speeds of trucks and automobiles.

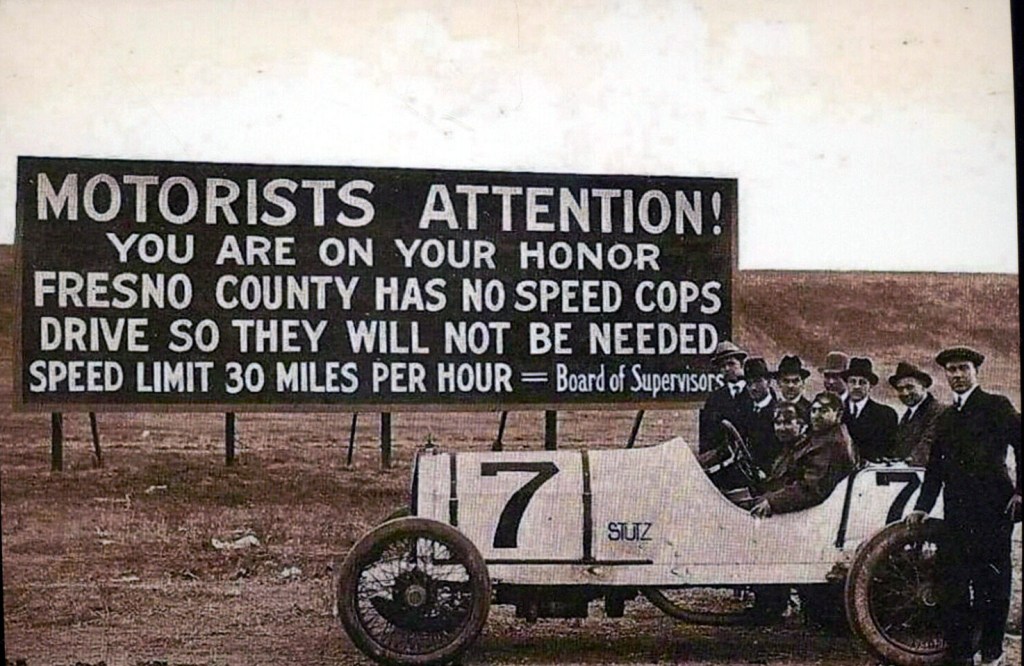

Highway 4 burrowed through the Newhall Tunnel and then up into the mountains past old Fort Tejon and then on to the oil fields and farmland of Kern County before riding along the majestic Castaic-Tejon Ridge and then twisting down to the first major town, Bakersfield. The rest of the way to Fresno traversed the so-called “Garden of the Sun” of California’s prime, irrigated farmland, the San Joaquin Valley, where, to either side of the road, were miles and miles of croplands, producing raisins, grapes, peaches, figs, nuts, olives, oranges, and other crops. The distance between Selma and Los Angeles is a little over 200 miles or almost halfway to San Francisco via Route 5 out of Stockton. The traffic would have been light in the morning, with occasional trucks and horse-drawn wagons, which Semnacher could easily pass in his Stutz motorcar, which shared the same engine with the two-seater Bearcat. Even though the first rains of the dry California summer had recently fallen, the weekend weather was expected to be fair with temperatures in the upper 70s.

Maude Delmont had a friend in Selma, Mrs. Anna L. Portnell, a divorcée, who was well-known in Fresno County society as a prominent member of the Woman’s Relief Corps and a celebrated bridge player. She later testified at the second Arbuckle trial in January 1922 under the name “Annie Portwell.” As a witness for the defense, she acknowledged that Delmont, Rappe, and Semnacher visited her ranch outside of town and that she took them sight-seeing in her car. During the excursion, Rappe allegedly begged, “Please stop the car if you do not want me to die.” Then Rappe left the car doubled up and drank “a quantity of dark colored liquid from a gin bottle. She said it was an herb tea.”[1]

Mrs. Portnell kept the bottle and produced it for the court. That she had kept such a souvenir of Rappe’s visit for nearly five months aroused no incredulity, at least none that was reported in the press. The purpose of having Mrs. Portnell testify was to further pile on that Rappe, despite being made sick by alcohol, drank it nevertheless. For that reason, as Arbuckle’s lawyers insisted, her getting sick at his Labor Day party was nothing unusual for this woman. Gavin McNab and his colleagues, however, must have had to choose between Rappe’s alcoholism or another of their theories, that she suffered from cystitis. Herbal teas were often prescribed to treat the disease before antibiotics. Alcoholism, of course, was more compelling. (Maude Delmont admitted to bringing a bottle of whiskey with her. She also testified that Rappe and Semnacher didn’t partake.)

Semnacher and Delmont never described what they and Rappe did in Selma, even though it was their only destination and the original plan was to return to Los Angeles. Perhaps they played bridge, since Mrs. Portnell made four and Rappe was herself a skilled player. That changed on Sunday morning, September 4, when Semnacher and his two passengers departed Selma for the long drive to San Francisco. He testified that the new itinerary was Rappe’s idea.

Before leaving Selma, Rappe dropped a postcard in a mailbox informing her “Aunt” Kate Hardebeck that she was having a “lovely time” and that she wasn’t coming home yet.

On Sunday evening, Semnacher and his party checked into the Palace Hotel. He took two adjacent rooms with a connecting door. Rappe and Delmont were to sleep in one room and Semnacher in the other. In the morning they would dress and have breakfast.

Meanwhile, Arbuckle and his party were already ensconced in a corner suite of the St. Francis, rooms 1219–1221, the same suite he occupied in June, with a view of the city that gave him pause. “I’d like to spend the rest of my life just looking out at Geary and Powell streets,” he said then to a reporter. “I’d have to give up a lot of palm trees and flower gardens to do it—but it would be well worth while.”[2]

[1] “Selma Woman Testifies at Actor’s Trial: Mrs. Anne Portwell Tells of a Visit of Party During Trip,” Fresno Morning Republican, 26 January 1922, 1.

[2] “Parade Honors Fete Beauties Today,” San Francisco Examiner, 18 June 1921, 13.

In another post you make it seem like there was some kind of ulterior motive for Delmont accompanying Semnacher on this journey. Delmont even going so far as to ask if Rappe was “friendly people.”

What do you think that motive was? Whose idea was the trip originally? Semnacher and Delmont’s? Or were Semnacher and Rappe planning to go, then Delmont just tagged on?

LikeLike

The journey to Selma, as described by Maude Delmont and Al Semnacher in testimony, was a layover. Semnacher was a businessman and likely a part-time procurer or, to use the dated term, “white slaver.” As a talent agent, his job was to find bodies to put in front of a camera and any consequent situations as a matter of course and, again, “business.”

Delmont was certainly an extra who provided benefits when there was no other way to make ends meet. One of my hypotheses is that she was a spotter for Semnacher, a trusted source for finding the right people for the camera and for the milieu behind it and in front. She was on a first name basis with Arbuckle. She really was rather loyal to him until he left San Francisco and a dying girl under her care without any money.

“Friendly people” in the context of old Hollywood, on the street, that meant people she could trust, people who drank lquor and, if not, wouldn’t object to her doing so. “Friendly people” wouldn’t object to her conduct at a gathering where there might be drinking, dancing, and consummation in the side rooms and even the bath-. “Friendly people” meant women who might engage in what could happen, whether by consent or peer pressure or rude force (a “rough” situation, to use her word). She didn’t want to meet strangers, “good girls,” so to speak, who might not understand.

That said, I don’t think anyone at the Labor Day party were new to each other. They belonged to the same demimonde that cut across film colony class boundaries. They all knew one or more of the partygoers and there was an element of trust—that word again. Delmont and those in room 1220 knew that special, in-group rules applied to their Jazz Age symposium, and this was especially true for the Jazz Age hetaerae who provided the entertainment. (I don’t think Rappe was one—yet—having lived as the girlfriend of a “high-status” individual until Lehrman’s studio failed. Her role model was really her mother without the drug addiction.) There had to be trust should such a gathering result in a misadventure that brought on “notoriety” as the partygoers understood it, especially for their host and his stakeholders.

As for Maude Delmont’s motivations, she was an extra who lived on the fringe of Los Angeles in the 1910s and ‘20s. She wasn’t smart enough to be an extortionist. Whatever Frank Dominguez had on her was bluffing. Being an extortionist requires a certain work ethic, a certain cleverness. Delmont lived too much on the fly, out of a suitcase. She was where Rappe might have gone with her life had she survived the Labor Day party. She didn’t want to be a fallen “kept” woman like her new friend, the wife of one Albert Royal Delmont, Maude’s “Cincinnati millionaire.” (Incidentally, he ended up here toward the end of his life and is buried in the same cemetery where my grandparents are interred.) At her age, her motivations were to maintain a certain subsistence level, from one day to the next, in a dry LA (it was dry before Prohibition), with no fixed address, save for the aunt who took her in, and keep it there until something better came around, a drinking companion with some family money, say, a dentist’s son.

The book goes into much detail. So, let’s wait for that. But loaded questions are always good practice should I ever get on the Dick Cavett Show (oh, wait . . .).

LikeLike

Thank you for the detailed reply. Sorry can I just clarify something – do you think San Francisco was always the goal for the trip, with Delmont just lying about the reason?

LikeLike

If you mean the conversation between her and Semnacher outside the Pig ‘N Whistle, she had to be chary about saying too much about the meet-up in SF As I have it, Semnachervery likely intended to go to SF with Rappe, Helen Hanson, and Maude Delmont. He wasn’t making this investment in time, money, and talent just to spend the night in Selma and then drive back on a Sunday. I think he had the long weekend ahead and intended to conduct business (which is a ductile term in Hollywood since it mixes pleasure). There was no real reason to be in SF for one afternoon. I posit some ideas for coordination and the very good reasons not to speak of it–which Delmont didn’t do.

The journey was a circle, too. Semnacher let on that he wanted to leave in time to drive on to Del Monte for the evening of September 5. There was something to see there: the state golf championship (Pebble Beach). Two of Rappe’s girlfriends were throwing a party that night, too.

But then Arbuckle let on something too, at the third trial, which I need to check against the transcript but shows up in newspaper accounts of his second time on the stand. While he previously said that he intended to board the SS Harvard on Sept. 6, 1921, at the third trial, while being cross-examined, that he wanted to test a new car and drive on to the golf championship at Del Monte. So, you must be satisfied with that for the present.

LikeLike