A new version of the arguments is being drafted (as I write) delivered before the jury near the end of the first Arbuckle trial of November–December 1921. The first draft had been based on very detailed reportage. The trial transcripts, however, differ markedly from the paraphrased versions in published in newspapers.

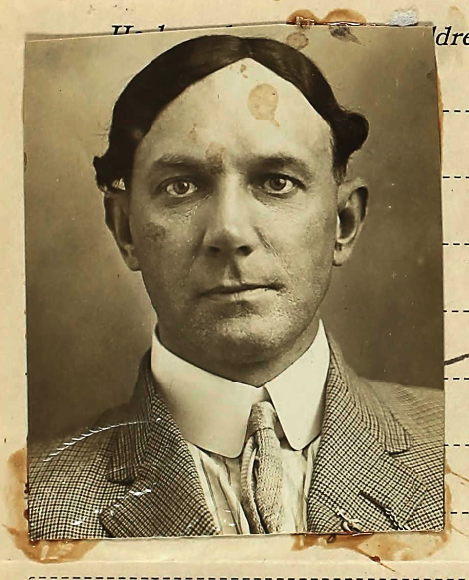

What follows is the end of the section devoted to Gavin McNab’s defense of “Fatty” Arbuckle.[1] Its title is derived from the Rev. James Gordon, the same Rev. Gordon whom Sidi Spreckels called to Virginia Rappe’s bedside. The clergyman, writing in his new column, described McNab’s speech as a “Celtic prose poem” after McNab’s rich Highland accent, which made him sound as much like a Presbyterian divine as a lawyer.[2] The man who followed McNab, with closing argument for the People, Milton U’Ren, was not as sanguine. To him the Good Samaritan described below was a “moral leper” and inspired another kind of outburst of faith: “Thank God, he will never make the world laugh again.”[3]

Had it not been for Maude Delmont being an unreliable witness, there would be no reliance on Zey Prevost or Alice Blake. All three women, for men who remembered the Preparedness Day bombing, always posed the risk of blowing up the People’s case. Every one of the district attorneys had a hand in planting those bombs in their own case, most of all Isadore Golden, who had come up with the compromise “hurt.” Still, that is what those showgirls undersigned. And, lest anyone forget, the “unfortunate circumstances,” the “wine party” as McNab put it, that event still resulted in murder to the prosecutors. They just needed to bide their time for a little longer and weather the dated lawyerly magniloquence of the 1800s autodidact showing off for the jury.

McNab’s had a working lunch. He met with his colleagues to discuss his performance and to go over the record and what had not been covered. There had been no mention of Jesse Norgaard, whose testimony suggested that Arbuckle had been obsessed with Virginia and that he disrespected her as well, and women in general, given whatever joke he intended to play.

Nat Schmulowitz surely and tactfully expressed a concern for the way medical evidence had not been exploited thoroughly. McNab had only burnished the reputations of Dr. Shiels and Collins brighter. And he had yet to draw on the Chicago affidavits, Albert Sabath’s contributions. One had been read into the record—and three doctors the day before certified that Miss Rappe was diseased. She had cystitis, which, to these conferees who had been holding back on leaving her reputation alone, was virtually a junior venereal disease in keeping with the late junior vamp.

And so, when the trial resumed at 1:45 p.m., McNab linked the medical commission’s report to “the testimony of Dr. Rosenberg of Chicago.” This evidence revealed that the defense had been right in contending that the young woman’s bladder had “defects,” that it was not the “perfect organ” the prosecution contended. Even that realization elicited another opportunity to preach to the jury as if it were the choir. “It would be an assurance trespassing on the domain of Divine Providence for any lawyer to intrude into the mysteries of nature and say what caused that rupture,” McNab intoned.

But the disease for which we have contended had been established. Whether that contributed materially to the disorder, we do now know, nor have any of the medical men on either side who have appeared before you pretended to tell you what did. All they could say to you was that many things might have done so. This leaves it with you of any direct testimony, outside of the medical and of the surgical demonstrations, to determine what probably brought about this young woman’s demise.

McNab, of course, did not want jurors to glance knowingly at Arbuckle’s girth—the District Attorney’s murder weapon that had been turned against the comedian. And so jurors who had already made up their minds, the reporters, as well as Arbuckle and Minta who knew better, now heard McNab deliver a paean, a panegyric devoted to the exercise of impartial judgement. “We do not ask you to give him any consideration because he is a great artist,” McNab said, without being ironic again, “or because he had brought joy into the world, or because he has made a success of his life. [. . .] This man without any disfigurement in this case, because there was not the slightest testimony reflecting on his character.”

The prosecution’s case, McNab reasoned, was based entirely on “conjecture.” As for the Arbuckle’s version of events, in response to all that had been made up about him, McNab made it a special point that his side made no objections during “two hours and twenty minutes of crucial cross-examination.” That was unheard of. That only proved Arbuckle’s candidness before the people of San Francisco and the nation. Then McNab waxed into a Cross of Gold speech made of diamonds.

That is the story. And you heard the story in its simplicity of how he tried to help this woman in the distress that had come upon her, and which was a common experience in her life, as is established without a contradiction, and how actuated by the spirit of mercy, you see this picture of this man crucified before you as a wicked character, in speech but not in evidence, carrying the limp body of this injured girl down the corridor of the hotel, staggering with her weight. Was this an unkind man? Doesn’t that tell the story, open for the world there to look at what went on behind the closed but not locked doors? [. . .] And he has told you in simple words what happened, and it exactly corresponds with this great, big, warm-hearted man, this rough diamond, perhaps, but still a diamond, carrying that injured girl down thru the hall; a more pathetic and a more beautiful picture than he ever put on the screen.

“There is to my mind a beautiful thought in connection with this thought,” McNab said in afterthought, that counsel had “not asked about the pictures that this man produced, but has anybody ever suggested that anybody ever saw an unclean picture of Roscoe Arbuckle? I think sometimes that the instincts of childhood is the most accurate of all instincts of the human race.” And yes, McNab really did impress upon the jurors the notion that Arbuckle himself was a juvenile. That gave his lawyer a fitting way to end of his Celtic sermon. “I always am impressed,” McNab said sagaciously,

with that beautiful spiritual suggestion of the Savior, “Suffer little children to come unto me.” And the childhood of the world, the instinct of childhood, had been accurate from that day to this, and this man who has sweetened human existence by the laughter of millions and millions of innocent children comes before you with a story of a frank, open-heated, big American, and submits the facts of this case in your hands.

To this a bored Leo Friedman, speaking for the People, asked McNab if he were done.

[1] People vs. Arbuckle, First Trial, “Argument of Mr. McNab, on Behalf of the Defendant,” 2188ff.

[2] James Gordon, “Minister Tells Highlights in ‘Fatty’ Case,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, December 1, 1921.

[3] People vs. Arbuckle, “First Trial, Closing Argument for the People, by Mr. U’Ren,” 2269ff.