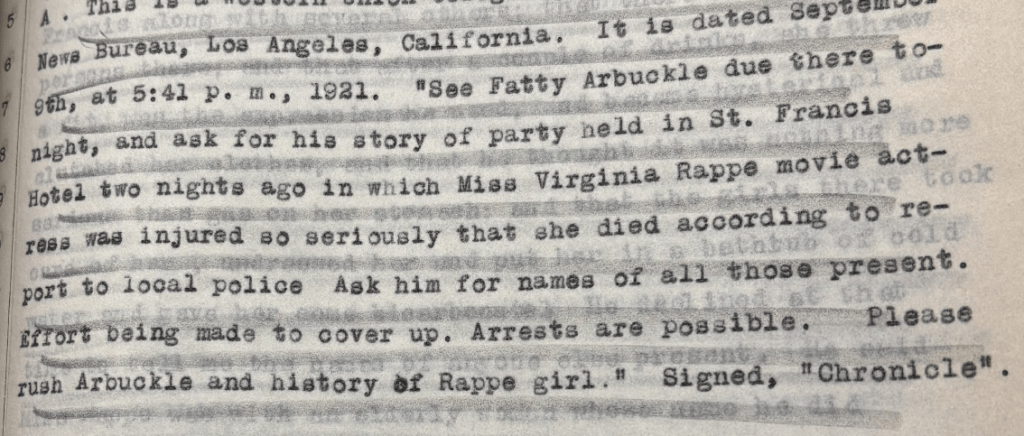

Last week, I worked on the Arbuckle trial transcripts at the San Francisco Public Library, filling in the gaps from my December 2024 visit. My familiarity with the course of all three trials, including every participant and their background, has served me well. It’s a kind of meta-understanding that makes everything in the transcripts intelligible, which you cannot get reading them cold. But that doesn’t mean I’m not surprised at the latest revelations.

In my book, two people are on trial for rape, although it is called “manslaughter”: Roscoe Arbuckle and Virginia Rappe. And they must be presented in a way that is dualistic. Arbuckle is still the famous, smiling comedian, suitable for the children in the audience. He is also a man with an appetite, not only for food and liquor, but female company. His reason for being in San Francisco on Labor Day 1921 was for casual sex with an escort, a “call girl.” He does play a part in his own misadventure. So, too, Virginia Rappe. She got her telephone call in the Garden Court of the Palace Hotel.

I don’t think she misunderstood what was expected of her—and she did not live up to expectations. I see her trying to frustrate them, buying for time as she engages in conversation with Arbuckle—keeping him talking and joking. So, too, Rappe’s wanting a piano when it came time to dance. Arbuckle said no one knew how to play. Rappe did. She played a good “party piano.” But he overruled her and ordered up a victrola from the front desk of the St. Francis Hotel. She would have no excuse not to be a dance partner as the midafternoon approached and well before she could be—what?—extracted by her manager for the 130-mile road trip to Del Monte before nightfall. Then she had to use the bathroom in room 1219 and was cornered.

Then she had to be either a “good fellow,” as Maude Delmont, the companion provided for her by her manager (who may very well have pimped his women to get them work and his percentage). Or Rappe could choose not to be so “good.” My working hypothesis is that Rappe had learned to keep a certain distance from men so as not to be sexually exploited or abused. The defense mechanism had been imprinted in her youth. Nevertheless, she still wanted the benefits, so to speak, of the comedian’s good will. The risk was worth taking. After all, there were other women at the party when sex raised its ugly head.

Such a hypothesis requires as much background as possible about Rappe and that begins with her childhood and who served as her earliest influences. She had a grandmother who served as “Mama” to both her and the adult sister who was, in fact, her birth mother. The grandmother wasn’t related to either of them. She had interceded in some way. So, what kind of family breakdown or tragedy led to this arrangement? And how did that affect the course of Virginia Rappe’s life? We get so close here in the following extract from the third trial. But it has nothing to do with the res gestae.

Milton Cohen, one of Arbuckle’s lawyers, is very methodically and respectfully cross-examining Kate Hardebeck, Rappe’s adoptive “Aunt Kittie.” Here he is trying to get at the mystery of Rappe’s origins in order to present to the jury anything dubious about her character, something that will exonerate Arbuckle and redirect the blame. There is nothing new in that. It is perfectly lawyerly. But there is more context. This trial takes place in the heyday of social Darwinism, when considerable emphasis was placed on genetic factors as well as environment in determining one’s morality or lack thereof.

Alert to the possibility of seeing the victim pushed from her pedestal, the prosecutor, Milton U’Ren, waits for the right moment to object.

Q. Do you remember how you happened to meet Virginia’s grandmother, or I mean Mrs. Virginia Rap[p]?

A. I knew the grandmother some years before and her mother, Mabel Rap[p], and I had lost track of them, and I had friend who had met them in the meantime, A Mrs. Tomlee, who had known me for years, and she took me their home again.

Q. How did her grandmother pronounce her name, Rap[p]?

A. Rap[p]?

MR. U’REN. Of course, if your Honor please, this family history is very interesting but I think it is entirely immaterial, irrelevant and not proper cross-examination.

MR. COHEN. They have gone back, if your Honor please, to the history—

MR. U’REN. No, we have just gone back to the acquaintance of this witness with Virginia Rappe, in regard to her health, and while it may be very interesting to find out the family branches of all the witnesses that appear upon the stand, I do not think that it can add anything to the knowledge of the jury as to how Virginia Rappe came to her death.