We first became aware of Gouverneur Morris’s interest in the Arbuckle case in Greg Merritt’s Room 1219 (p. 208). He refers to the following “open letter.” Our take is this: the letter was likely written before Gouverneur Morris began to turn in his editorials about the Arbuckle case and trial to the San Francisco Call (see Document Dump #5). These pieces were intended to be daily and were syndicated by the editor of Screenland, Myron Zobel.[1] He appears to be the “recipient” of this letter. For such copy to be published in time for the November 1921 issue of Screenland, where it appears on page nine next to a drawing of Mary Pickford, Morris would have been commissioned in late September or October—weeks before the actual trial, which isn’t referenced in this letter. The murder charge, which Brady sought in September 1921, is the giveaway here as to when this letter was actually composed. And one can see this as well by reviewing Morris’s copy for the Call. In the piece published on November 14, 1921, the first day of jury selection, Morris once more endorsed Matthew Brady, calling the district attorney “honest and big hearted, who has a greater faith in probation than prison.” The other pieces that Morris turned in are soberly written and don’t really take sides. Indeed, the writing for the Call differs so much from the Screenland letter that what you will read here was likely ghost-written by someone else with a different agenda.

An open letter to the Editor of Screenland

By Gouverneur Morris

In presenting Mr. Morris’ letter, the Editors of Screenland are thoroughly cognizant of the prudish caution that would argue suppression of such a daringly frank arraignment. Mr. Morris, however, is not only one of the leaders of American contemporary fiction, but he is a student of criminology, as expressed in many of his fiction works. This distinguishes Mr. Morris’ contribution from any mere morbid analysis of the Arbuckle case and removes any hesitancy Screenland might feel in presenting such a discussion before its readers.

Editor, Screenland Magazine

Hollywood, California

Dear Sir—[2]

In the Arbuckle matter Los Angeles seems to have butchered herself pretty thoroughly to make a San Francisco holiday. That the church should lead in howling down a man innocent of any crime in the eyes of the law has to have been expected, but that experienced editors and the man in the street, and the man in the studios should have so lost their heads, and their Americanism, is deplorable and a little surprising.

Los Angeles has a big chance to be big, open-minded and just. Instead, she listened to the pleading of a San Francisco district attorney and went crazy. Even a Mayor, in a frenzy of righteousness agreed that it is deplorable to raise people from the “lower orders” and make millionaires of them.[3] What does the Mayor of an American city mean by the “lower orders”? And what is American for if it is not to furnish equal opportunities to all men? And men are not raised. They raise themselves. And God knows it is finer to rise upon the love and laughter of children, as Arbuckle rose, than upon the back of any mercenary campaign—even if one rises all the way up from the “lower orders,” whatever they are.

It looks to me as if the Prosecution aspired to raise itself from whatever order is theirs, to positions of prominence in California, and believes that a hanged Arbuckle (guilty or not guilty) would be of immense political advantage to them. They will be able to “point with pride,” etc., etc.

Before jumping so hard on Arbuckle, decent-minded people not carried away by hysteria would like to know a little more about the woman who is said to be the victim of his crime, and of the drunken woman who alleges that the crime was committed.

It may be that Virginia Rappe was afflicted before she went to the famous part, and that Arbuckle is no more responsible for her death than the policeman who arrested him.

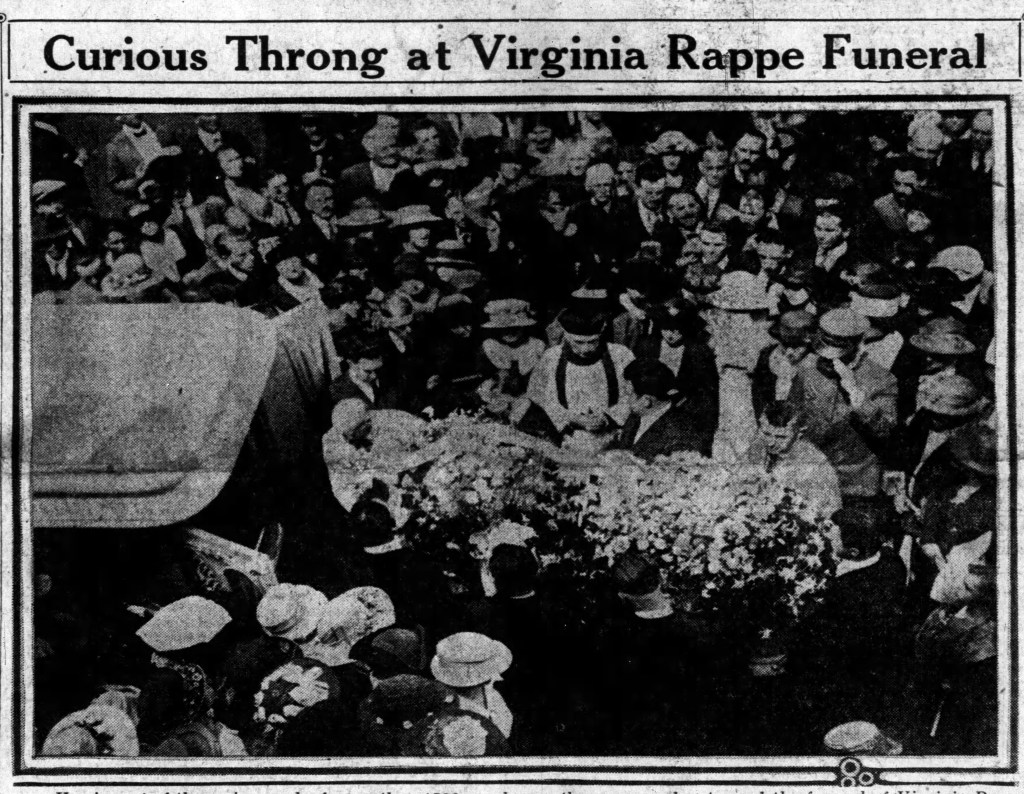

I for one would like to know more about her “sacred” love affair with this fellow whose bombastic telegrams and excruciatingly vulgar funeral arrangements have been the most sickening part of the whole business.[4]

And what sort of person is our chief witness for the prosecution? Is Delmonte her real name? If not, what is? What has been her vocation or avocation? How drunk was she? And after she has sobered up does she remember well what has happened while she was in liquor?

But it is not too late for the Los Angeles [people] to demand fair play for the victim of the San Francisco cabala and to accord it. Suppose we remember how much the kiddies love “Fatty” and give him the benefit of every doubt, and ask to have his pictures shown on Broadway, until there is no doubt of his guilt and well—and tell those in San Francisco to go to the Devil, and behave like regular men and women.

I do know Arbuckle, but, because of the laughs he has given my kiddies and me, I am his friend until there are better reasons (than now exist) for believing that no man should be his friend.[5] And surely it can’t be so bad as that.

Gouverneur Morris

[1] Not to be confused the other Myron “Global” Zobel, the travelogue filmmaker.

[2] I.e., Myron Zobel

[3] I.e., George E. Cryer,

[4] I.e., Henry Lehrman.

[5] Morris had two teenage daughters.