The following passage from our work-in-progress. Here we end our discussion of Virginia Rappe’s mother, Mabel Rapp and segue from her involvement with a wealthy young Chicago black sheep and check forger to her untimely death. Like other parts of the book, here we correct the mistakes made by other authors and disprove the myth that Mabel’s daughter, Virginia Rappe, appended the lowercase e to Rapp.

Such a revelation hasn’t been picked up yet by Wikipedia. We would rather someone else take the honor. FamilySearch.com is a valid source. You must search for “Rappi.”

The passage below also corrects her daughter’s middle name. It wasn’t “Caroline.” That can be corroborated by the 1910 Census.

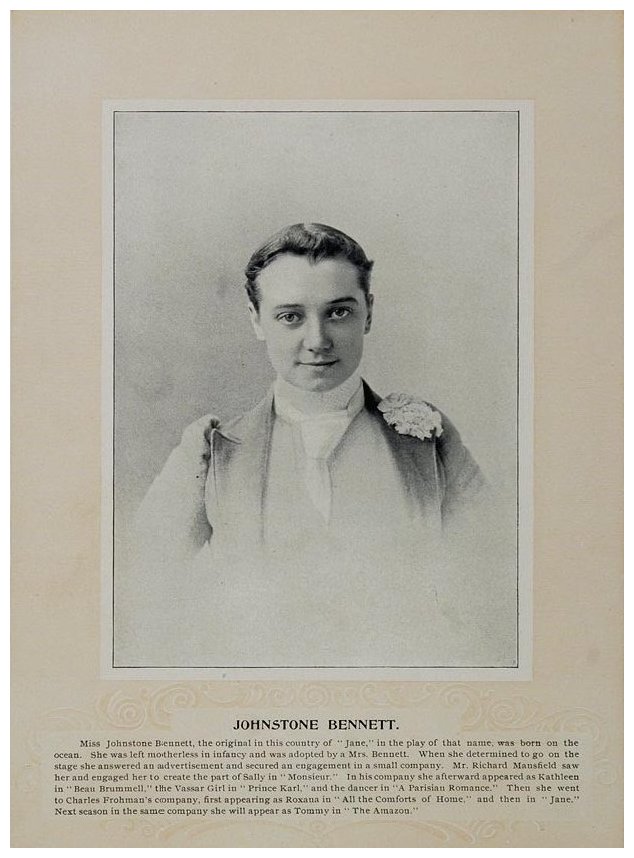

While this may seem pedantic, such facts have a deleterious effect on the factoids told by others. Ultimately, we present a victimology and a revisionary history of the Arbuckle trials. Incidentally, we are still conducting research for certain voids. This includes finding an image of Mabel Rapp (and even a very young Virginia Rappe} from the 1890s. We know that Mabel resembled the actress Johnstone Bennett, who also died of a similar form of tuberculosis in 1906.

Frank Parker and members of his gang, some of whom belonged to other wealthy Chicago families, were eventually released from jail for lack of evidence. Augustus Parker was reunited with his errant son who took up residence at the Auditorium Hotel and regained his listing in the Chicago Blue Book of 1900. During the last two years of his life, the elder Parker saw his investment of money, love, and tolerance pay off as his son joined the family firm and began to work his way back to Chicago from the Omaha office. Frank Parker lived in a succession of boarding houses, married in 1914, and died at the age of 49 in January 1918.

Mabel Rapp’s life—and that of the daughter seemingly absent from her life—also changed with her separation from Parker. But where he had the means to reform himself back in Chicago, Mabel had far fewer. She relocated to New York City to start a new life with her daughter in tow. There was likely little choice given the notoriety she had attracted in Chicago and the possibility of fame in the other city’s vaudeville circuit. The syndicated columnist Marjorie Wilson, during the weeks after Virginia Rappe’s death, interviewed individuals who knew of Mabel in New York in the early 1900s. They claimed that Mabel reinvented herself in the dance halls and theaters around Times Square as a performer who

dazzled admirers with her vivacity, her coquetry, her physical perfection, as she had done in Chicago. She sparkled in the chorus of Lillian Russell’s comic opera company. [. . .] She had little time for mothering the baby Virginia. The two lived at boarding houses and hotels and some of the time in a little flat on the outskirts of Greenwich Village. The baby called her “Mabel.”

Although Wilson refers to Virginia as “a baby,” she was old enough to attend grade school. And her “sister” Mabel was surely not the only one raising or supporting her “kid sister.” The woman who served as grandmother or mother to Virginia, depending on the time, place, and context, was certainly on hand.

Mabel Rapp had also added the extra syllable to her name with an acute French accent. But her reinvention as Mabel Rappé proved short lived and likely worse than maudlin as Wilson continues.

Probably it was to forget the mistake she had made, the place she had lost socially, that Mabel Rapp became a queen of night life in the cafes, drowning bitterness, sorrow, disillusion in waves of sensation, craving the excitement of gay music, the admiration and caresses of men, the tinkling of wine glasses, dulling the pangs of the misery of the past in the superficial pleasure of the moment.

Life in New York was good for a time. Mabel, her “mother,” and her “little sister” lived at 247 W. 50th and, later at 359, just off 8th Avenue in the heart of Hell’s Kitchen not far from the “Tenderloin District,” a neighborhood known for its gambling dens, burlesque halls, and poolrooms—and “creep joints,” the lowest kind of brothel, where patrons were robbed. Mabel, however, more likely provided for her family as she always had seeking out male admirers as a chorus girl in various Broadway productions according to Variety, whose informant, in 1921, also recalled an anecdote about Virginia Rappe. At the time, the automobile was “just coming into vogue” and Mabel and her kid “sister” were often seen being chauffeured to and from their apartment building, chased by street urchins teasing Virginia and calling her “Gasoline Zealine.”

Mabel had made a new life for herself and her family in New York City while her health gradually declined. She coughed. She spit up blood. On December 21, 1904, her condition had worsened to such an extent that she was taken to old St. Luke’s Hospital, near the cathedral of St. John the Divine on Amsterdam Avenue. She lingered over the Christmas holiday and died on January 7, 1905, in the early hours of the morning, attended by a Dr. Capito.

Mabel’s Rapp’s death certificate reveals she died of chronic pulmonary tuberculous and tuberculous adenitis, that is, scrofula. Once called the “king’s evil,” for it was once believed that if the English monarch touched the sufferer’s throat, the disease would cease to spread in its grotesque fashion. Thus, Mabel’s final moments would hardly resemble anything like the romantic notions of consumption found in, say, a popular novel of her day, Camille. Mabel’s fine neck and pretty face were likely disfigured by swellings and ulcers. She would have been unable to swallow.

Her death certificate is the only document that recorded her embellished name at the time. The informant also spelled the deceased woman’s father as Henry Rappé. The informant also knew the maiden name of the first, the real Virginia Rapp, Mabel’s mother. Of course, the woman who succeeded her, who cared for Mabel’s daughter and maintained the charades of mother, daughter, sister could have provided such details that make this document one of the few that seems honest. So, too, could the thirteen-year-old Virginia Z. Rappé.

There was a funeral in Chicago but no obituary in the newspapers. There were likely a few friends present but no family beyond the two who accompanied Mabel’s body back home, the woman who called herself Virginia Rapp and the adolescent Virginia Rappe. As for Mabel’s brother, Earle Rapp had grown up into a respectable young stock broker in the Chicago Exchange with an office in the Rookery building. He had a wife and a baby daughter. His child had been born in wedlock—and a man of his position relied on the trust placed in him. He could hardly risk being associated with his sister’s notoriety—or risk that of his niece seventeen years later.

Adapted from Spite Work, The Trials of Virginia Rappe and “Fatty” Arbuckle: A revisionist history

© James Reidel and Christopher Lewis