The mysterious death of Al Stein in the early hours of October 9, 1921, raised eyebrows a century ago in the weeks leading up to the first Roscoe Arbuckle trial. The following passage is another from our work-in-progress that highlights several “sideshows.” This one, we feel, deserves a sidelong look, so to speak, for the way it calls attention to two Labor Day partygoers: Fred Fishback and Ira Fortlouis.

Their conduct in the Arbuckle case deserves more scrutiny. Hence the detail below that might make the final edit in this or another form.

The day before the Paramount and Famous Players–Lasky brass met to discuss their Arbuckle problem, Universal Pictures and Hollywood’s film colony suffered another casualty attributed to alcohol and a dissolute lifestyle. The dead body of Fred Fishback’s personal assistant, Albert F. Stein, was found in Los Angeles during the early hours of Sunday, October 9, one month after the death of Virginia Rappe. Propped up by two pillows on the floor of his bedroom, his face had turned blue from having choked to death. The only mark on his body was a two-inch scratch on his face. Newspapers described the scene at the Golden Apartments on 1130 West 7th Street as a “liquor orgy,” which began when Stein returned home with three men just before midnight on Saturday, October 8.

Stein, the son of a Jewish bookkeeper and his Mexican American wife, was twenty-seven when he died. During his short life, he had married, fathered a son, and once played professional baseball in the California leagues for a minor league team owned by the Santa Fe Railroad. Although he was good enough to be a prospect for the St. Louis Nationals and the Chicago Cubs, Stein decided against the life of a minor leaguer and instead sought work in motion pictures.

Stein’s real talent wasn’t in front of the camera but behind it. He quickly rose in the ranks at Sunshine Comedies, where he came under the wing of Henry Lehrman and undoubtedly was in almost daily contact with Virginia Rappe between 1919 and 1920 at the Culver City plant—where Stein, too, experienced the frisson of having Roscoe Arbuckle and Buster Keaton working in the neighboring studio.

When Lehrman started his own company in 1920, Stein was promoted to casting director. When his mentor went bankrupt at the end of that year, Stein was quickly picked up by Fred Fishback for Century Film Corporation, where Stein continued to work as an assistant and casting director. Naturally ambitious, Stein served Fishback well and was expected to take charge of one of Century’s units in November.

In a series of articles in September, the New York Daily News tried to make sense of what happened to Arbuckle and Rappe at the St. Francis Hotel by investigating the culture and mores of the film colony. Men in Al Stein’s position were known to take advantage of the opportunities that culture created. “There is a lascivious maxim concerning the gateway to success in the pictures,” that screen tests were a stock joke. “Strict vigilance does not always prevent refractions,” opined the Daily News given the anecdotal evidence. “[N]ot long ago a casting director was discharged after rumors of questionable affairs with women seeking parts in pictures.”

Although Stein wasn’t the man in question, he was no exception and the rigors and pleasures of his motion picture work took a toll on his marriage, more so than the away games of his brief baseball career. When he died, Stein was already divorced and cohabitating with two “studio girls,” a term used for aspiring young actresses who had yet to make a screen debut or still worked as extras and showgirls. The threesome began shortly after he moved into his apartment in September. A blonde, whom he registered as his sister, Mildred Bellwin was followed by her friend, a redhead, Jean Monroe. Both were members of the Pantages Broadway Follies. They were his first responders on the October 9.

According to their statements to the police, they kept to their rooms and did not see Stein and his friends. Their story, told in an “airy” manner, suggested that the gathering was a stag party. When it ended around midnight, however, both young women joined Stein in his bedroom and just “talked” for about an hour. Then the women retired to their shared bedroom and left Stein alone in his.

Another hour passed and Monroe was awakened by a “terrible gaspy, creepy noise of some kind,” as she described it, “a ghastly thing to hear at 2:30.” She woke her roommate. When they found Stein, he was lying half out of bed with his head on the floor and his feet still under his bedclothes. They splashed his face with cold water. But his breathing became more labored, he began to turn blue.

Monroe and Bellwin then called Stein’s older brother Carl, who soon arrived and summoned a doctor—and the police. But it was too late. His brother had already passed.

According to the police, wine and whiskey bottles littered his room and the kitchen. A bottle of “moonshine” was also found—and a pronounced scratch on one of Stein’s heavy cheeks. Asked to explain the scratch, Stein’s roommates said it was self-inflicted two days earlier. He had picked up a nail file in their presence and said, “It’s funny how people hurt themselves with things like this.” Then he proceeded to draw the blade across his cheek. But that wasn’t the only thing that was strange about the scene in Stein’s bedroom.

When police searched his billfold, they found a list of names and telephone numbers that, according to the Los Angeles Times, “indicated that he had a wide field of women acquaintances.” Also found was a telegram addressed to Ira Fortlouis at the Century Film Corporation from District Attorney Matthew Brady dated September 19 that read: “Please report to district attorney’s office, San Francisco, immediately.” On the back in pencil, was a note, presumably the text of wired response to Brady’s request. But it wasn’t from Fortlouis: “Will be at your office tomorrow noon—Fred Fishback. Leaving for San Francisco today.”

Stein’s billfold contained one more mystery. There was a check for $25, made out to Fishback by the director Frank Beal and endorsed by Fishback. On the surface, it seemed as though Fishback delegated some personal business to Stein and used Brady’s telegram like a scrap of paper.

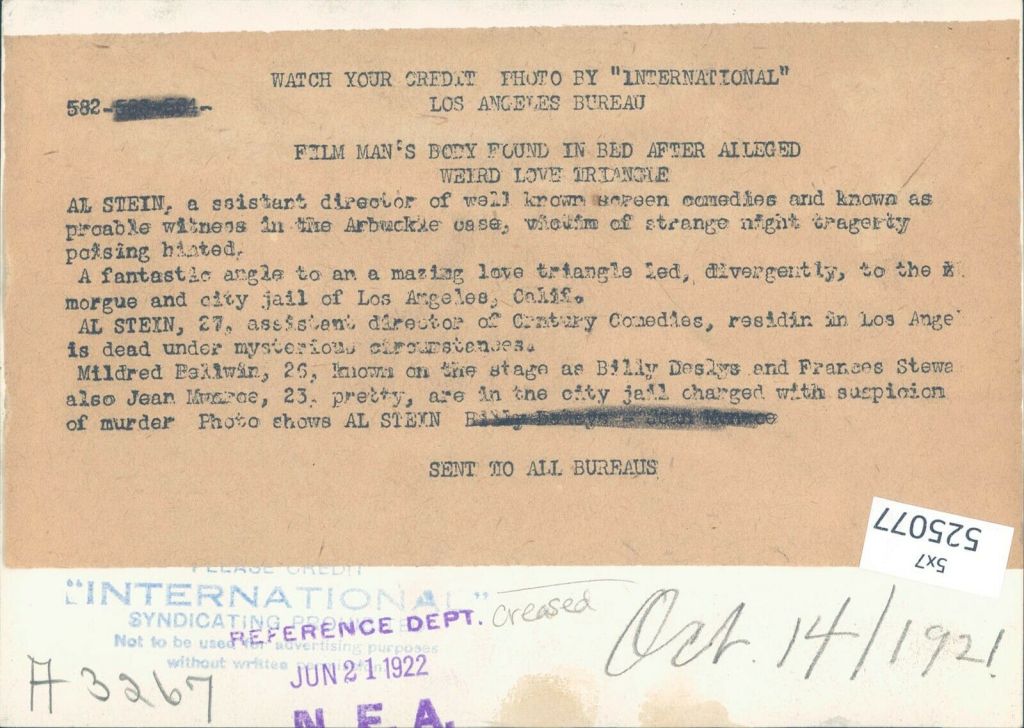

Bellwin and Monroe were subsequently jailed on suspicion of having poisoned Stein—and Fred Fishback again found himself associated with a scandal involving alcohol, showgirls, and death—at least until a better explanation was found for the Brady telegram in Stein’s wallet.

Two Los Angeles police detectives spoke to Fishback. They had a theory that Stein had been summoned to San Francisco as a potential witness for the prosecution. They believed that he could have been murdered since none of his drinking companions had suffered the same ill effects. But what the detectives learned from Fishback provided no further clues and was likely little different from what the director told the Los Angeles Times. “I have known Al Stein for several months,” Fishback said,

and in all my dealings with him he had been sober and industrious. I did not know that he was a drinking man. I was greatly shocked to hear of his death and immediately offered to do what I could. Who the two girls are I do not know. The only time I saw them was last Friday, when I stopped for a moment at Al’s apartment on business. I asked him then if both the girls were living there in the same apartment and he explained that he merely occupied the front room while they occupied the rest.

When no poison was found in Stein’s stomach, the coroner determined that he had died of acute alcoholism. There was no foul play. Stein’s brother Carl, for his part, knew nothing of an alleged drinking problem. He said his brother Al was subject to heart attacks and suffered choking fits.

In the end, Stein’s roommates were only charged with “vagrancy” and released. Fishback made the funeral arrangements and the case quickly faded before Matthew Brady arrived to conduct his “open house” in Los Angeles. There was no curiosity on his part. His deputy, Milton U’Ren, only said that Stein didn’t “figure in any important connection in the case against Roscoe Arbuckle”—nor could he address why Stein had in his possession a telegram intended for Ira Fortlouis.

Al Stein (Newspaper Enterprise Agency, private collection)

Reverse.