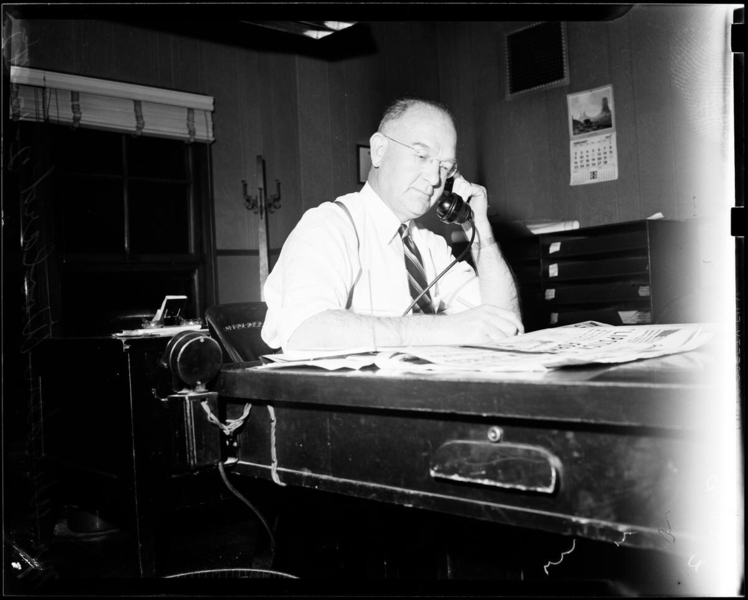

During the second Arbuckle trial of January 1922, the District Attorney of San Francisco, Matthew Brady, subpoenaed a witness who shed light on the comedian’s conduct in the immediate aftermath of Virginia Rappe’s during the early afternoon of September 9, 1921. This was Warden Woolard, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times. His purpose was to contradict Arbuckle’s testimony from the first trial in November on two points: (1) whether he had been alone in his hotel bedroom with Rappe; and (2) whether he had locked the doors. Although Woolard no longer had his notes, he had a good memory and was on the stand with much to tell.

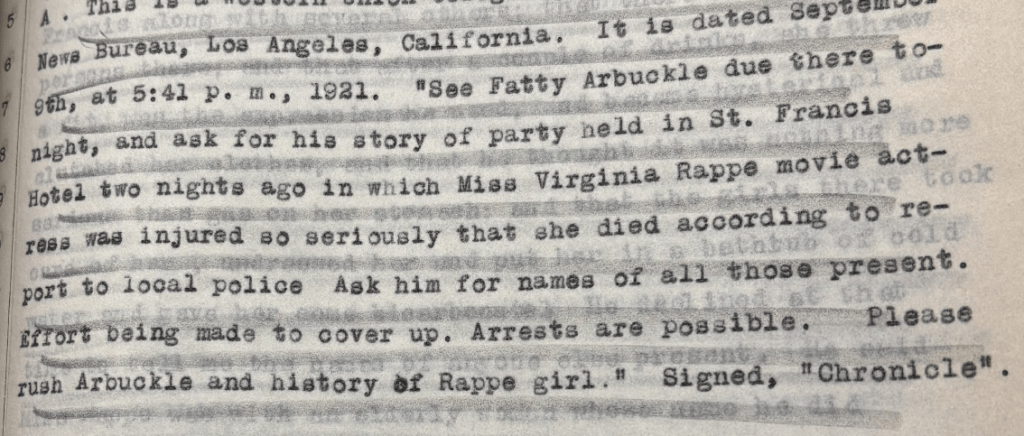

He was prompted to meet Arbuckle by a telegram from the San Francisco Chronicle. It was hard not to ignore its urgency—and both newspapers would sell plenty of copies by sharing information. The Chronicle wanted answers from Roscoe Arbuckle about his Labor Day party of September 5.

The Times sent Woolard to Arbuckle’s Tudoresque mansion on W. Adams Street. The reporter arrived arrived just after 7:00 in the evening. He rang the bell and was met at the front door by an attractive woman who identified herself as Arbuckle’s secretary. This was Catherine Fitzgerald (see “Arbuckle’s housekeeper, secretary and escort: Catherine Fitzgerald”). He gave her his card and she told him to wait outside.

If you are familiar with The Day the Laughter Stopped (1976) by David Yallop, who claimed to have used the trial transcripts to write his book, he describes a rather different scene on p. 132 that was surely intended for a screenplay that any assiduous research would have spoiled.

At 10:30 p.m. that Friday evening, Roscoe Arbuckle sat quietly studying the script for his next picture. The doorbell rang and his butler opened the door. Two dozen reporters charged past the butler, knocking him over. They poured all over the house, taking photographs and looking for Roscoe. Surrounding him, they began to fire questions based on the statements that had already been made in San Francisco by Maude and Alice. [. . .] “Is it true that you screwed five women during the afternoon?”

That is not how it went. According to Woolard, Arbuckle soon appeared. The comedian asked Woolard to follow him away from the house, so that they could talk in private. Arbuckle did not need to be told about what happened in San Francisco earlier in the day. Friends had informed him of Rappe’s death.* And, as their conversation began in earnest, the actor Lowell Sherman joined the two men on the sidewalk. He had apparently come from a back door. Arbuckle denied hurting Rappe. He had only pushed her down on a bed to keep her quiet. And so on. This is in Wallop, all taken from Woolard’s reportage the next day, September 10, as well as that of George Hyde of the Chronicle.

Arbuckle wasn’t “studying” the script for a silent film. Instead, Lowell and other partygoers were getting on the same page and had been getting on that page during the afternoon of September 9. And this continued into the night, when Woolard attended a meeting held in the office of Grauman’s Million Dollar Theater. What Woolard curiously omitted from his testimony was the presence of Arbuckle’s first lawyer, Frank Dominguez. The first thing he did was school Arbuckle with the understanding that anything he said needed to be made only with the advice and consent of counsel. So, I will attempt to square this in the work-in-progress. It may have simply been a courtesy extended by the journalist to one of the most important criminal defense lawyers in Los Angeles during the 1910s and ’20s, the kind of man you heard when he said, “I’m not here,” and you wanted to keep your job.

Warden Woolard did. He went on to enjoy a long and storied career, including assigning reporters to the Black Dahlia case. George Hyde, who likely wired the Times for the initial scoop and wrote the first columns about the Arbuckle case for the Chronicle, either resigned or was released soon after. He went on to testify at the third trial. But offered very little in substance. He came and went from the stand in minutes. His career took another direction. For a time, he worked for various newspapers in Los Angeles, including the Times. But he was never assigned to anything like the death of Virginia Rappe again. For a time he the publicity agent for the evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson. Eventually, he returned to San Francisco, where he poisoned himself in July 1932, “in a fit of despondency,” after a long period of unemployment.

*This was really one “friend,” Rappe’s manager Al Semnacher. He may have monitored her decline, which provided more lead time for damage control. The problem for Arbuckle was his own hubris and the absence of his personal lawyer, Milton Cohen, Dominguez’s law partner, who was en route from New York during this critical time.