One of the preconceived notions that we had to shed—at least temporarily and more than once—was that Virginia Rappe was heterosexual. We left her sexuality open for discussion for the present and beyond if there is a future interest in the hoary notions that surround this mysterious woman whose death ended the career of Roscoe Arbuckle.

Previous Arbuckle case narratives, even Kenneth Anger’s gay eye, see Rappe as “straight” and that she slept with the comedy director Henry Lehrman during her years in Hollywood from 1916 to 1921. That was, of course, enough time for her to marry him or move on to someone better, hypergamy being Hollywood’s way then as now. But something about her being with just the one man raised our eyebrows. Was it love or something else? Then we took a hard look at the way Rappe referred to him, as “Mr. Lehrman.” While it seems like nothing, here she implied a certain professional distance, that she was just one of his performers, an employee. Only after her death was he seen as her “sweetheart,” that they were to marry. In reality, when Rappe accepted Roscoe Arbuckle’s invitation to a party in the St. Francis Hotel suite on September 5, Labor Day 1921, she had long since parted ways with Lehrman. Rumors in the film colony suggested Lehrman had even encouraged her to attend the party. Could there have been a less obvious dynamic to their relationship? Did Arbuckle test or cross a boundary that had been in place for Lehrman as well?

Lastly, we took another hard look at her female friends. Some seemed to be “beards” of another species. The friendships seemed same sex so as to fool the opposite.

Virginia Rappe was raised by women. There was her birth mother, Mabel Rapp, considered a beauty but also a “tough girl” in Chicago’s South Side during the 1890s, variously called the “Queen of the Night” and the “Queen of Chinatown.” But her daughter had been raised believing Mabel was her older sister. Both had the same guardian, an older woman with a heavy Irish accent, who went by Virginia Rapp. Her real surname was Gallagher and she wasn’t related to either Virginia or Mabel and her taking the name Rapp was likely to explain away the strange family dynamics before anyone asked questions given the mores of the 1890s.

When Mabel died on January 7, 1905, her New York City death certificate had been informed with the name she used in her last years—Mabel Rappé—and the names of her real parents. Yet another rabbit hole for the curious to explore. Another notice—more about her absence from Chicago than her passing—appeared a few months later in The Club-Fellow: The Society Journal of New York and Chicago. The author of the spicy “Audacities” column recalled Mabel working a Wisconsin lake resort’s ballroom like a proper courtesan of the Gay Nineties.

It is only a few years ago that the Johnstone Bennett-like Mabel Rapp (who was supposed by many to be the daughter of Partridge of dry goods fame) used to frequent a certain Chinese laundry on State street near Sixteenth street kept by a Celestial known as “Chollie,” and there forget all troubles in the “long draw” [a hit off an opium pipe]. Mabel has disappeared from State street and “Chollie” has also vanished and returned to the land of flowers and hop [opium].

The last time the fair Mabel was seen was at a German [formal dance] at Fox Lake, when several of the men made up a pool to see whom the lady would favor. George Holyoke (who, by the way, married Mrs. Elmer Flagg of Thursday Club recollection after she had lowered Elmer to half-mast), George, who was a forty-to-one shot, got the prize. Several of the married men present were much perturbed for fear the identity of Mabel might become known and cause friction in the domestic circle. “Billy” Lyford, was conspicuous by his absence, and most the “papas” sough the veranda, it being too warm to dance.[1]

The names mentioned above belonged to subaltern society people who belonged to various social clubs in Chicago. The men, whether single, married, or divorced, knew Mabel had a reputation for fun . She made herself available as a dance partner to the well-heeled gents of Chicago and opened the way to other forbidden pleasures, such as opium and a dalliance with a beautiful woman from across the tracks, a real habitué of the South Side demimonde.

What is interesting, however, is the comparison made to Johnstone Bennett. Bennett who was a well-known stage actress and male impersonator hardly resembled a fallen Gibson Girl as Mabel had been made to be as she cruised Fox Lake.

Johnstone Bennett had an unusual past. Her name was derived from the two women who raised her. She started playing “tough girl” roles early and was considered the epitome of the New Woman by the novelist Willa Cather, especially in regard to her dress on- and offstage. Bennett in the photographs found at the New York Public Library’s special collection was boyish in appearance, which may have actually made her more risqué to her male admirers as much as she appealed to women who preferred same-sex relationships with a more “butch” partner.

Johnstone Bennett (New York Public Library)

Bennett’s career flourished in the 1880s and 1890s and could have served as role model for Mabel, who had more than one opportunity to study Bennett on the stage in plays such as The Amazons, a comedy that was a great success in Chicago in 1894.[2]

Three years after Mabel Rapp’s death, her daughter first came to the public’s attention in the Chicago Tribune as a kind of sleeping beauty, with the potential to be

one of the world’s famous models after the years have mellowed her and taken from her posing the sight touch of childish gaucherie which still remains. [. . .] She is a simple little girl of 15 years who looks out on the world with the clear, dewy eyes of a child just awakened from sleep.[3]

The “tough girl” mask wasn’t right for Virginia Rappe though, her style and path were closer to that of an ambitious ingenue. By 1908, Rappe was being mentored by a woman she first knew as “Dot” Nelson but whose married name was Catherine Fox. She saw Rappe’s potential as an artist’s model and as an entertainer. Mrs. Fox paid for dance lessons and likely pushed Rappe toward the theater and vaudeville stage. Both vocations—model and performer—were seen as morally risky for a young woman still in her teens. The prettiest ones attracted a male following. Lovers, however, were discouraged. Traveling vaudeville and theater companies made women sign contracts that forbade them from seeing men without being chaperoned. This protected their employers from losing girls to marriage, an unintended pregnancies, and like pitfalls of being intimate with men, such as venereal disease, drug addiction, alcoholism, and the various forms of duress attributed to rejection.

Rappe undoubtedly understood that appearing virginal if not an actual virgin protected her career and her person. This meant having established boundaries with any male companions.

Rappe’s only known long-term courtship in Chicago was with a real estate broker named Harry Barker, but whether this included a sexual element is questionable. Any suitors were screened by her putative grandmother and the former neighbors who acted as de facto guardians: Mrs. Fox and Kate Hardebeck. Both witnessed Rappe refusing an engagement offer from Barker after what had to have been a frustrating crush–courtship. But he and Rappe remained friends during her lifetime.

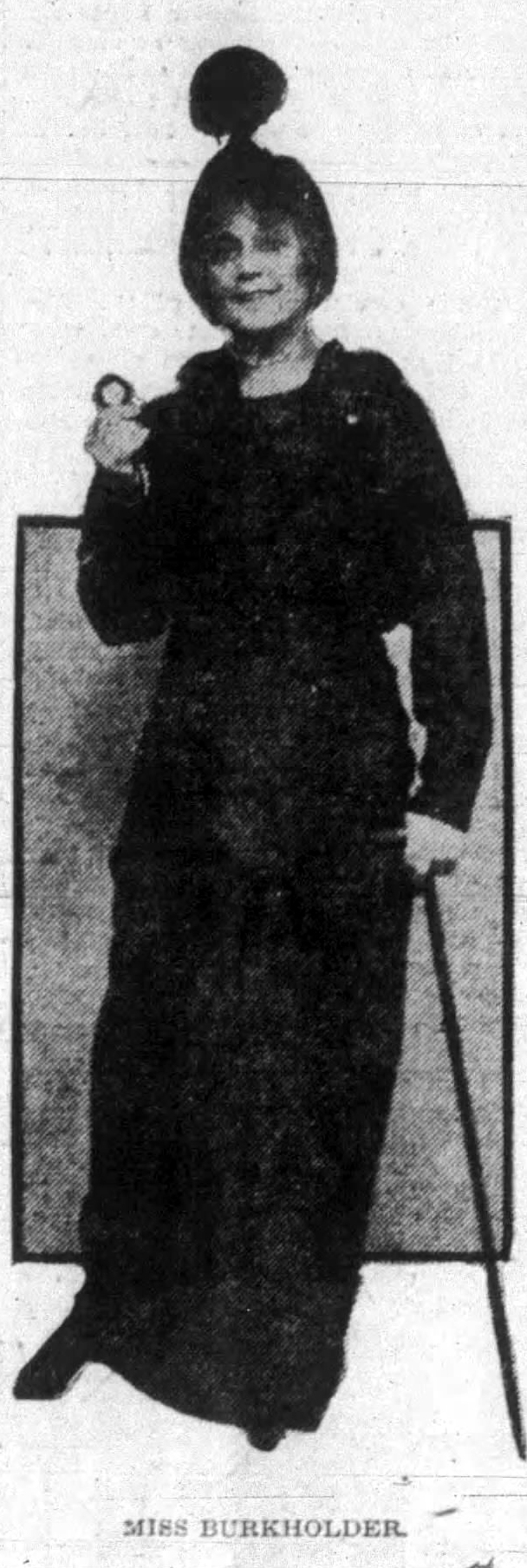

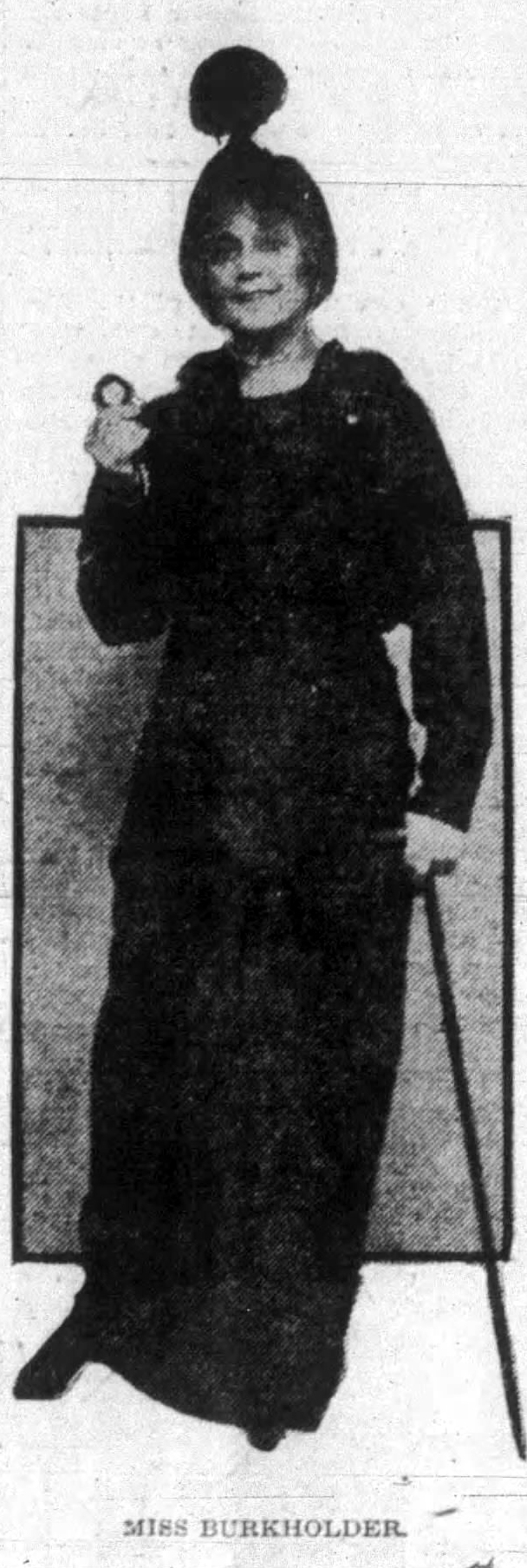

Other than Barker, Rappe was most often reported in the company of women her own age. Winifred Burkholder, the owner of an early modeling agency, was an exception.

Burkholder met Rappe first as a model, after the latter had set aside any stage ambitions, and later as a fellow student at the Art Institute of Chicago between 1908 and 1911.

Like Rappe’s guardians, Fox and Hardebeck, Burkholder was also married. But she had left her husband and son in rural Wisconsin to pursue a career in fashion design. And to avoid any indelicate questions about her marital status, she claimed to be a widow or unmarried.

In late 1912 Rappe and two sisters from Chicago, with whom she shared a hotel room on a trip to New York, made the news when they announced they had made a pact never to marry.

While the sisters eventually broke their promise, Rappe kept hers and joined Burkholder’s traveling Promenade des Toilettes of 1913—a fall fashion revue that toured department stores in the Midwest and South, which also featured six other young women billed as the “Troupe of the Wonder Models of Fashion.”

Burkholder was an imposing figure shepherding her models from city to city. She sported a monocle and a cane—and, as a model herself, wore matronly outfits to appeal to the older, more demure customers.

Winifred Mills Burkholder in Omaha, cane and monocle, September 1913 (Newspapers.com)

Rappe’s role in the review was to promote the “tango dress,” Daring because the skirt showed glimpses of her ankles and calves up to her knees, the dress was also intended to titillate men more than to appeal to the conservative tastes of the American heartland. When interviewed about the show for the Atlanta Constitution, Rappe teased about her disappointment in the men of Atlanta.

“When it comes to speed,” spoke Virginia, “this town is on the ‘Fritz!’ See? ‘F-R-I-T-Z!’ The combined speed of the whole of it would put ginger into a grasshopper. We’ve been here three days—think of it–and the only entertainment we’ve had the entire time had been . . . I hate to mention it, but you girls remember that little taxi ride we paid for out of our own dear, hard-earned bank accounts?

“True, we gave a tango party to ourselves. The management stopped it. Even locked up the ballroom. Did you ever? Shameful? No! Certainly not! Outrageous!”[4]

When one of the other models decried the lack of attentive male company—who might be willing to entertain them—Rappe chimed in, “Search me, they haven’t been around here.”

To Mrs. Burkholder this was the desired outcome, that the women got attention with their sassiness yet kept to themselves.

The Troupe of the Wonder Models of Fashion, October 1913 (from the Atlanta Constitution accessed in Newspapers.com). Rappe lies supine in the front. Mrs. Burkholder is on the left.

Following the Promenade des Toilettes, and with the money they had earned during the tour, Rappe and another model, Helen Patterson, sailed to Europe to spend most of December in Paris and New Year’s Eve in England before departing from Liverpool.

On their return journey, the friends made an impression on the first-class passengers and crew of the RMS Baltic, dancing the tango together and wearing their bloomers exposed at the ankles, making for “four pink puffs” as they walked arm in arm on the promenade deck. Photographs of the pair were printed in newspapers in January and February 1914. The woman made an impression with the “tango bloomers,” their appearances in the ballroom, and as partners during the shipboard bridge games.

None of this conduct—either in Atlanta or aboard the Baltic, would have raised an eyebrow in the early twentieth century, no more so than in a cotillion at a boarding school for girls. But the tango was seen as an erotic dance, a courtship dance—and the pairing of Rappe and her girlfriend, nevertheless, made for body language that discouraged men from making advances.

Helen Patterson and Virginia Rappe, January 1914 (Newspapers.com)

If one puts out of mind the testimony of the two Chicago abortionists and a bordello physician who claimed Rappe had bore a child, indeed, more than one, a case could be made that Rappe might still be a virgin and remained “intact” into 1915, when, at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, she was briefly touted in the press as being engaged to an Argentinian diplomat Don Alberto M. d’Alkaine, vice consul and secretary to the commissioner of his country’s exhibit.

Virginia Rappe, 1915 (Newspapers.com)

Most Arbuckle case narratives accept this engagement as authentic because it was newsworthy in 1915. But the San Francisco Call attributed Rappe as the source of the rumor in late July. Soon after newspapers from coast to coast picked up on the romance and included a photograph of Rappe in profile, wearing the hat of a pajama suit that she likely designed and repurposed in this photograph to make it seem more bridal.

A month later, the Examiner reported that the couple had parted ways, noting that when the engagement was announced neither party denied it. Don d’Alkaine returned to Buenos Aires and a long diplomatic career. Rappe returned to Chicago and didn’t stay long at all.[5]

Like the pronunciation and spelling of Rappe’s surname—variously Rapp, Rappé, Rappi, Rappe, or even Rappee as it was heard and spelled in Atlanta—her sexuality lacks fixity. While leaning toward a preference for the company of men, when the question of marriage and conjugal relations became a reality, Rappe seemed to have baulked again.

It’s possible that up to that time Rappe had had no real or lasting relationship with a man that was consummated.

While newspapers from Green Bay to Muskogee to Shreveport to Omaha printed fashion photos of her and framed her as a kind of ur-influencer of women’s wear, not one photograph showed her with Don d’Alkaine. He only appears in group photographs of various dignitaries and it is hard to tell what he looked like.

Nor did she ever appear in a photograph with the next man in her life, Henry Lehrman.

As we have it in our work-in-progress, Lehrman could have met Rappe during the second half of 1915. Both had worked for Mack Sennett and belonged to the same circle of friends around a San Francisco power couple, Jack and Sidi Spreckels.

In the early spring of 1916 at a fashion parade around a Los Angeles racetrack for the Actors’ Fund Memorial Day benefit. Rappe drove a FIAT representing Lehrman’s L-KO Kompany.

At the time, Rappe was living at the Hollywood Hotel, a popular residence among those in the motion picture industry. Indeed, the perfect setting for an aspiring young woman who had “gone West” to become a movie star. But according to another resident, Anita Loos, who befriended Rappe, the latter lacked the ambition of the other young women who would do anything to get into pictures—including sleeping around. Instead, her focus was on getting Lehrman to pay more attention to her.

What Rappe did to pay for her room and board at that time remains a mystery. She likely had savings from her modeling career and allegedly had been hired for a few film roles though so small as to be uncredited. Instead, Rappe positioned herself to play another kind of role, one that was off-screen, that of a sophisticated “society girl” and as such found her way into the film colony. But where her mother had balanced multiple companions over the years, Rappe had become attached to just one man, one dance partner.

Prior to Rappe, Lehrman was thought to prefer visiting prostitutes so her presence probably gave him an air of respectability around the men who bankrolled his films, such as William Fox, who funded his new company, Sunshine Comedies. Not only did two-reeler comedies have to be “clean,” so did the men and women who made them—and Lehrman was entrusted with million-dollar budgets. Thus, Rappe served to make Lehrman more respectable and less of a workaholic and loner, as he was made out to be in the Los Angeles Times, however, the “couple” went virtually unnoticed in the press until September 1921.

My, my, how these satellites do blaze for a time! Now it’s a certain Henry Lehrman, who is cultivating the smart set. He looks like one of those suave gentlemen you’ve read about in French novels—quite an objet d’art, as it were. And he wears his little waxed mustache just so, and his hair bandolined[7] so tight and his feet in such snug pumps and himself in steinblochian[8] attire and with a Miss Rappe, who’s quite the season’s best-looking New Yorker. This Mr. Lehrman is occasionally seen at the Alexandria or at Vernon, and people who know him say he’s quite exclusive. Perhaps so; he’s quite often alone.[9]

Rappe was still living in the Hollywood Hotel in the fall of 1917 when Roscoe Arbuckle, having separated from his wife, actress Minta Durfee, lived there and lorded over the dining room with his entourage and practical jokes played on various unsuspecting fellow guests. By that time, Rappe had received a credit in just one film, Paradise Garden (1917), in which she played a “junior vamp” alongside Harold Lockwood. If the script was true to the best-selling novel on which it was based, Rappe’s character, the wealthy Marcia Van Wyck, also had a female companion, described as a poor relation who didn’t like men.

Although she took the part as a lark, the result of visiting the set one day with friends, Lehrman probably had some influence in her being cast. He knew the director, Fred J. Balshofer, from the time when both had learned their trade at the Biograph Company in New York.

Balshofer cast Rappe again in 1918 with newcomer Rudolph Valentino, pairing both as conspirators and lovers in a vehicle starring female impersonator Julian Eltinge. What footage survives shows that both had rapport in this propaganda picture set in occupied France and Germany during the First World War. But their characters suffered the vicissitudes of three different recuts and as many titles: Over the Rhine (1918), The Adventuress (1920), and The Isle of Love (1922).

Virginia Rappe with Rudolph Valentino (Margaret Herrick Library)

Rappe’s being cast in Paradise Garden was evidence that she had the looks and presence to get a career going but she seemed to be content being at the side of Henry Lehrman and didn’t seek acting jobs outside of bit parts she did for him.

Zaza in The Adventuress/Vanette in The Isle of Love (YouTube.com)

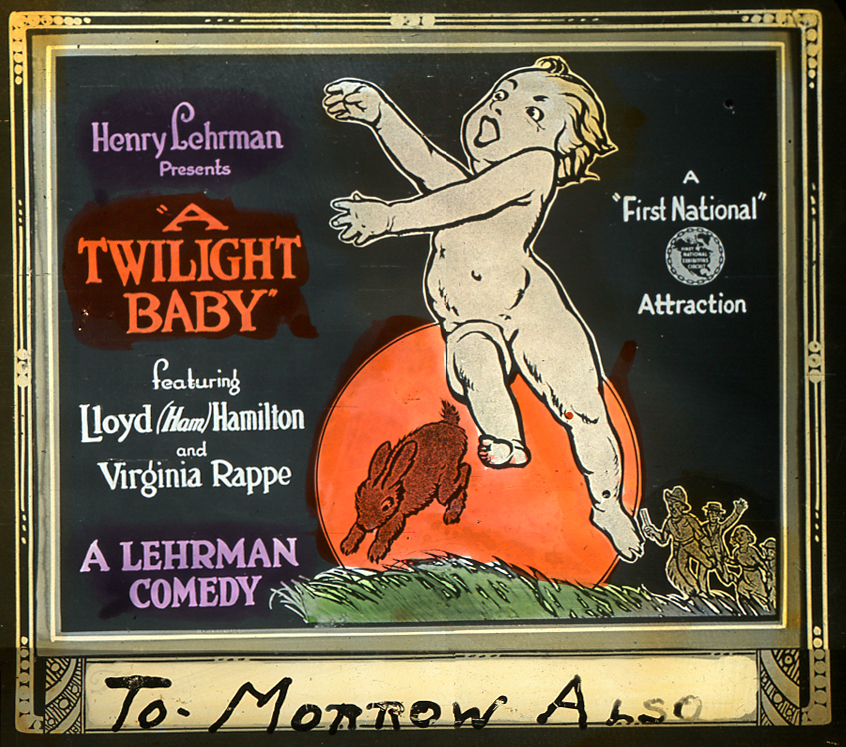

Lehrman produced comedies and, whatever his intentions were, he could save money by casting Rappe in his own films though she had none of the experience or training for comedy. Lehrman just needed her to be an appealing face. In one of her first roles, as the love interest for the film comedian Lloyd Hamilton in His Musical Sneeze (1919), she was given little to work with besides tired gags.

Lehrman continued to miscast Rappe at the Culver City studio, which he built in 1919 and shared with Arbuckle during the summer and fall of that year. By then Rappe was also Lehrman’s tenant—a sort of “rent girl” in his home at 6717 Franklin Avenue, where she was simply listed as a “boarder” in January 1920 according to census data.

There Lehrman provided her with a car and driver and his servants. Members of the film colony assumed that they were a couple but appearances can be deceiving—even to the jaded eyes of Hollywood people. If Rappe had to provide Lehrman with “benefits,” she was certainly inhibited from doing so by cystitis. Indeed, coitus for Virginia Rappe was likely uncomfortable if not painful. She would have known, too, that having sex with a man who also had had multiple partners would probably not aggravate her condition and probably give her something worse.

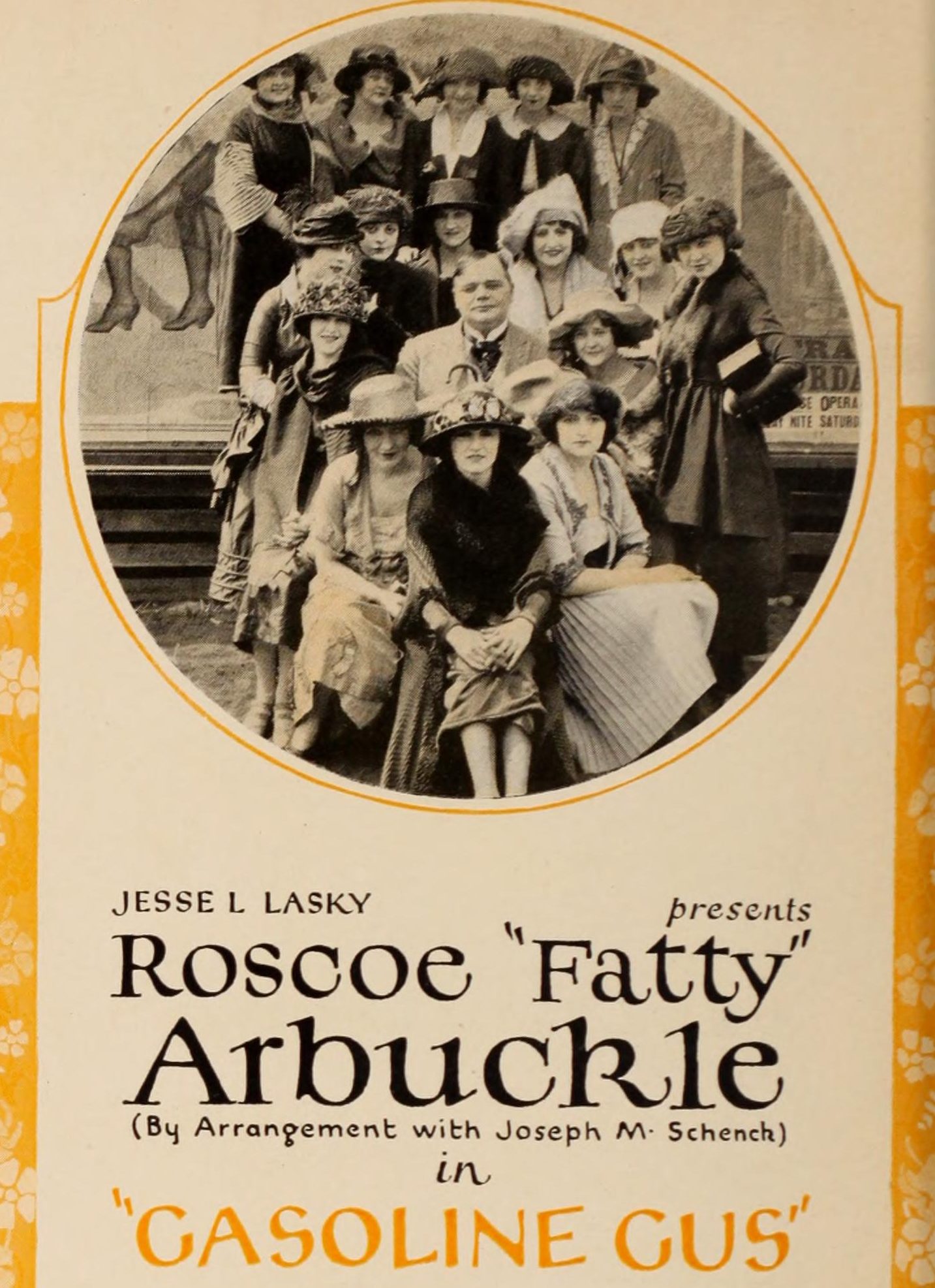

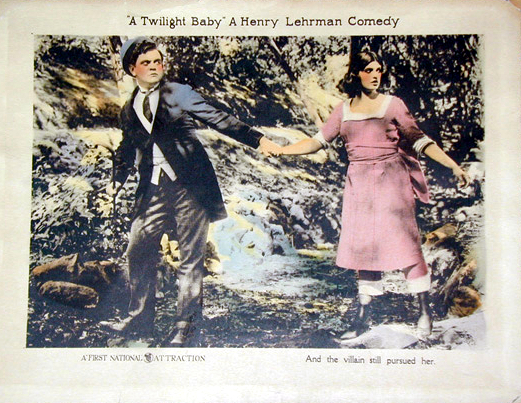

The relationship between Lehrman and Rappe was not so simple as boyfriend and girlfriend, she seemed to be obligated to pay him back with a number of motion picture appearances. The most prominent of these was in a role as a wholesome country girl in A Twilight Baby (1919), another vehicle for Lloyd Hamilton.

There was little news of Rappe following A Twilight Baby save that she wanted more serious roles. She and Lehrman seemed not to appear in public. In July, she was in San Francisco during the week of the Democratic National Convention. While she was listed as a guest in two hotels, Lehrman was making a film elsewhere. When he hosted a dinner for the Democratic candidate for president, James M. Cox, in Los Angeles in September, Rappe wasn’t present. Although she had a few more roles that only demanded she smile or bat her eyes, by the end of 1920 she and Lehrman split up. He was having financial difficulties. A creditor had filed lien on his house. As for Rappe, she had already moved out by midsummer. We know this because her telephone number, which she published in a July classified advertisement for her lost brindle bull terrier, was used by the landlady and boarders at 1946 Ivar Avenue. That is the address she used for her entry in the 1921 Los Angeles City Directory.

While living on Ivar, Rappe, in need of income, had taken on the management of a few rental homes on Canyon Drive, including one owned by actor Francis X. Bushman. This makes for a rather tangental episode in our work in progress and certainly speaks to the resolve and independence of Rappe.

That Rappe had an unusual arrangement with Lehrman doesn’t eliminate the possibility that they once loved each other. It can’t be ignored though that it would have been convenient for Lehrman to romanticize their relationship following Rappe’s death. He didn’t deny that he was her fiancé. To abandon her post-mortem would have made him appear to be a heel. Fortunately, he still had a photograph of her to show in his New York City apartment and helped the public imagine a loving couple suddenly destroyed by tragedy. What he didn’t admit to was the presence of a new girlfriend in his life, Jocelyn Leigh, a Ziegfeld Follies girl who was more ambitious and probably more willing to give him an escort in Manhattan if he would open doors for her in Hollywood (which didn’t turn out well for her).

For Arbuckle’s lawyers, his chances of acquittal rested on their narrative that Rappe was promiscuous and possibly a prostitute so they had to discount any evidence that she was a faithful partner, a frigid woman, or anything close to a lesbian.

During the comedian’s three trials, they made an issue of Rappe’s Chicago past. Prominent among them—and the only lawyer not to sit at the counsel table, was Albert Sabath, a personal friend and business associate Rappe’s alleged sweetheart, Harry Barker. Sabath deposed on two midwives and abortionists as well as a brothel physician to show that Rappe had suffered from bladder disease that could be attributed to being a promiscuous teenager and giving birth to at least two illegitimate children.

What was missing in the witness testimony—and Barker was one of those witnesses for Arbuckle—was any parallel conduct on Rappe’s part in Hollywood. Instead, these witnesses only saw Rappe have a few drinks that resulted in episodes of hysteria, including disrobing and tearing at her clothes.

These episodes resembled what Arbuckle and his other Labor Day guests saw when Rappe was discovered on his bed, writhing in pain. Naturally, we were suspicious that a person would have somehow made a routine of such extreme behavior. Arbuckle’s prosecutors were also incredulous. But it’s unlikely the witnesses would have repeatedly committed perjury with little to gain so it’s likely there was a kernel of truth in their stories. Though they were indeed defense witnesses so a little bit of exaggeration would not have been surprising.

One hypothesis we considered was that Rappe’s episodes—her acting “crazy” as Arbuckle called it—were a defense mechanism, indeed, a very ancient one that is still used to counsel women to prevent sexual assault and rape: “You may be able to turn the attacker off with bizarre behavior such as throwing up, acting crazy”—that is, behaviors that will depress sexual arousal.

What is so ancient about that? By feigning madness, of being touched by the gods or demons, superstitious rapists of a besieging army might have been more inclined to just pillage a conquered city rather than risk being possessed themselves. So, did Rappe act crazy when she thought she was being sexually threatened? Did Arbuckle encounter this—even when semiconscious as she was going into shock from a ruptured bladder?

That said, according to Lehrman, Rappe did worry about being assaulted, especially on her long walks in the Hollywood Hills. For that reason, she was accompanied by the aforementioned brindle bull terrier named “Jeff” over which she had much control. (He was ultimately found, by the way, and enjoyed one more year with his mistress’s companionship.)

Rappe and friends in Picture Show, 1920 (Lantern)

Ultimately, we wouldn’t have meditated this much over a woman who was ostensibly heterosexual and probably avoided being penetrated for hygienic reasons—not frigidity—in addition to the professional contingencies of keeping one’s figure, maintaining the illusion of being desirable and unattached to the movie-going male, and so on. Unlike her mother, Rappe never did anything like the cross-dressing Johnstone Bennett. But Rappe did leave for San Francisco dressed in what was called a “riding habit,” which consisted of riding pants, boots, jacket, and a jaunty cap. This was an outfit she often wore for her long walks.

Rappe’s riding habit and pants that anticipate Katherine Hepburn’s preferences (Authors’ collection)

What made us look twice and thrice thus far at her sexual aspect were the reports of some of the unmarried women who attended her her visitation and funeral on September 18 and 19, 1921, respectively. Mildred Harris was given the special privilege of being allowed to pray alone at the bier of “someone I loved.” This is the same young actress who had divorced Charles Chaplin the year before. Allegedly, the Little Tramp complained that, throughout their three-year marriage, Harris was more often with actress Alla Nazimova and her girlfriends, the so-called “sewing circles.” He allegedly said as much as well in responding to Harris’s accusations of cruelty during their contentious divorce proceedings. The source for this, however, is the notoriously unreliable Hollywood Babylon, in which Harris is made out to be unequivocally bisexual.

Grace Darmond was also present at the Rappe funeral. She was the girlfriend of Rudolph Valentino’s lesbian wife, Jean Acker, who was also close to Nazimova. And if either Nazimova or Acker attended Rappe’s funeral, no one noticed. But only a few weeks earlier, Acker and Darmond were vacationing in the Monterey–Del Monte–Carmel area during the long Labor Day holiday. They were still there on September 9, 1921, They hosted a dinner party at the Blue Bird Café for the actress Truly Shattuck on the day that Rappe died, September 9. Coincidentally Del Monte was where Rappe intended to stop for the night after her one day in San Francisco.

Another person of interest at the funeral was Kathleen Clifford, who accompanied beside Darmond, an actress who had established her early reputation in vaudeville as a male impersonator and was once billed as the “Best Dressed Man on the American Stage.” She was described in the press as a “dear friend” of Rappe’s in newspaper accounts.

Finally there was one other person, never identified by name, who seemed to have some attachment to Rappe. It’s unknown if she was at the funeral but our awareness of her existence is based on the testimony of Eugene Presbrey, a founder of the Screen Writers Guild and a resident at the Hollywood Hotel in 1917 when Rappe was living there. He, too, saw Rappe having a hysterical episode after drinking two cordials. But she was already “an abnormal character and good copy,” he recalled before this.

She traveled about the hotel with a constant companion, he said knowingly, a woman whom he described as “an unattractive ash-blonde.”[10]

N.b. Notice that we provide no convenient links to Rappe. Her Wikipedia page is woefully inaccurate and its minder(s) are welcome to borrow from us to revise and correct it.

[1] “Audacities,” The Club-Fellow, 12 April 1905, 5.

[2] Johnstone Bennett was forced to retire at the height of her career in the early 1900s and succumbed to tuberculosis in 1906—the same disease that killed Mabel Rapp.

[3] “Are the Artists’ Models of Chicago More Beautiful Than the Famous Models of Paris?” Chicago Sunday Tribune, 22 November 1908, 7:4–5.

[4] Britt Craig, “Gee, But Young Men of Atlanta Are Slow, Say Pretty Models Who Wanted Good Time,” Atlanta Constitution, 12 October 1913, 5.

[5] See “Argentine Official Wins Girl,” San Francisco Examiner, 29 July 1915, 5; “D’Alkaine Engagement Off,” San Francisco Examiner, 1 September 1915, 8. See also “Art Model Has Exposition Romance—Soon She’ll Be a Bride,” Day Book [Chicago], 7 August 1915, 15, for an example of the wire photo and caption published in various American newspapers.

[6] See “Chicago Best City for Girls,” Chicago American, 3 January 1913, 3; and “New Jobs Await Working Women,” Los Angeles Times, 3 January 1913, 4.

[7] Slicked back with bandoline hair dressing, cf. pomade.

[8] A suit made by Stein-Bloch Company, the maker of “Smart Clothes” for stylish men in the 1910s and ’20s.

[9] The Bishop of Broadway, “Men of the Town,” Los Angeles Time, 13 January 1919, II:2.

[10] Associated Press, “Says Rappe Was ‘Abnormal,’” Los Angeles Evening Express, 31 March 1922, 6.