During the third Arbuckle trial, in early April 1922, the prosecution called a surprise witness to the stand, Lillian Blake, a San Francisco photographer who claimed to have taken a single photograph of Virginia Rappe in September 1914. She testified that Rappe had spent about thirty minutes in her Geary Street studio.

Her purpose was to rebut the testimony of a defense witness, Helen Whitehurst, who claimed that Rappe attended her birthday party in Chicago in October 1914, where she drank an alcoholic beverage and fell ill. Arbuckle’s lawyers hoped to prove that she had a long history of exhibiting such symptoms as abdominal pain, hysterics, and tearing off her clothes, triggered by the effects of alcohol. These were the same symptoms she presented at the comedian’s Labor Day party on September 5, 1921.

Prosecutors contended that Rappe wasn’t in Chicago. Another of their witnesses said she was in New York during the autumn of 1914. A third also said San Francisco. Naturally, Arbuckle’s lawyer, Gavin McNab, used this confusion to his advantage. He asked the jury: How could Rappe be in two places at once? McNab could see the prosecutors were floundering. Their witnesses lacked credibility and the evidence was weak. As further proof that Rappe had been, at least, on the West Coast in late 1914, Blake held up an undated newspaper clipping of her photograph. She didn’t have an original.

We dug deeply for a source for that photo as we began to revise the work-in-progress. The problem was that Rappe wasn’t newsworthy on the west coast in 1914—except when she returned from abroad during the first week of January. She and another model made a splash when they exposed the frills and a good portion of the leggings of their long underwear or “pantalets.” Photographs of the pair aboard the SS Baltic appeared in U.S. newspapers for two months. Then she disappeared, leaving a void that Arbuckle’s lawyers filled with physicians who said they treated her and alleged companions in Chicago whose real lives proved to be, if we could use a contemporary expression, “sketchy.”

In the spring of 1915, however, Rappe’s image was again seen in newspapers across the nation as she began to publicize her new line of clothes. She also appeared in the society pages of some American newspapers in connection to her short-lived engagement to the Argentine diplomat Don Alberto d’Alkaine, who oversaw his nation’s pavilion at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

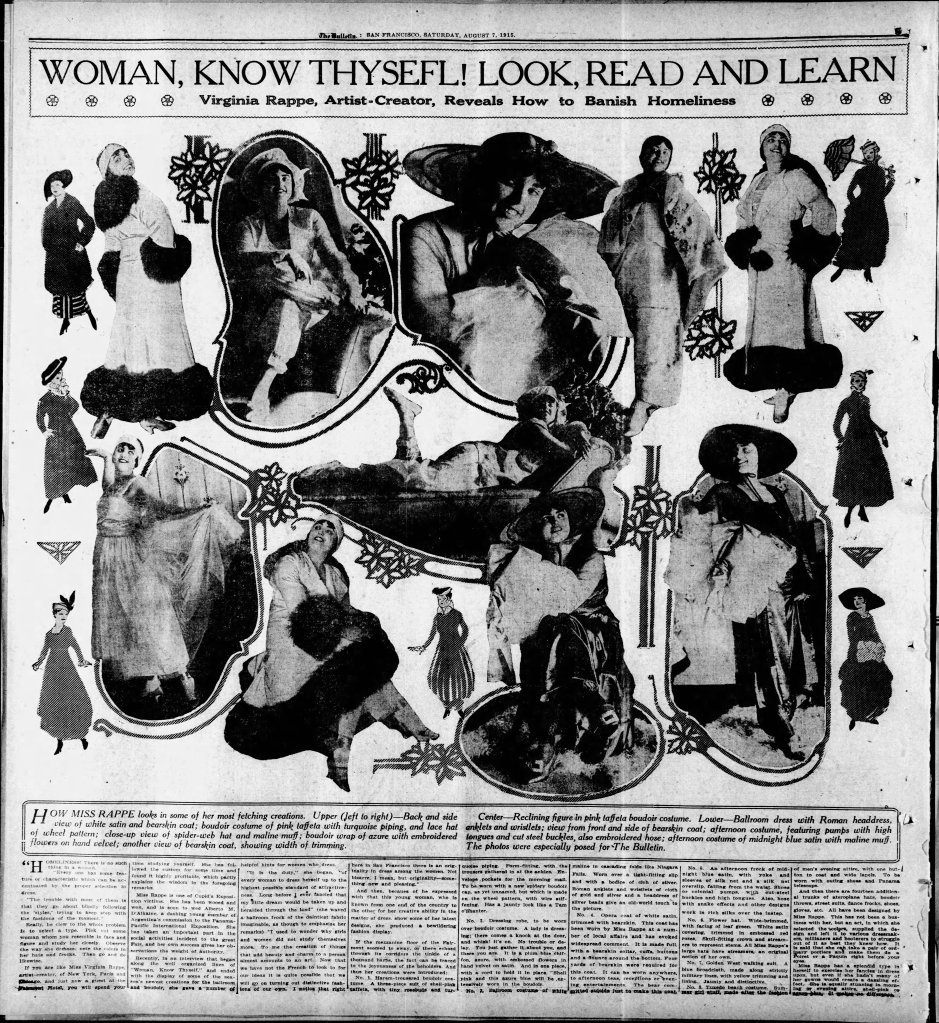

This made us question whether the prosecution co-opted one of these images to convict Arbuckle? We probably won’t ever know. But thanks to having more recently digitized and searchable San Francisco newspapers archives, we did uncover a little more of Rappe’s deeper connection to San Francisco and it does go back to September 1914. We discovered that Rappe’s liaison with d’Alkaine began around that time. The clue is a story in a front-page feature published in the San Francisco Bulletin in late July 1915. A week later, it was followed by a full-page spread devoted to Rappe’s design collection—and fashion advice.

What one can see below is that Rappe was committed to and invested in designing all kinds of outfits for women. So, why did she give it up—as well as d’Alkaine—for a precarious existence as merely the “best-dressed woman in Hollywood”?

Source: Newspapers.com.

Source: Newspapers.com.