(Occasionally, we will provide primary source texts that are related to the Arbuckle case. “Love Confessions of a Fat Man,” an interview with Roscoe Arbuckle conducted by Adela Rogers St. John was published during the second week of September and when Arbuckle was booked for the murder of Virginia Rappe. This is from the work-in-progress and serves as a transition from the second part, Los Angeles, to the third part, San Francisco.)

Intermission

It is very hard either to murder or to be murdered by a fat man.

Roscoe Arbuckle

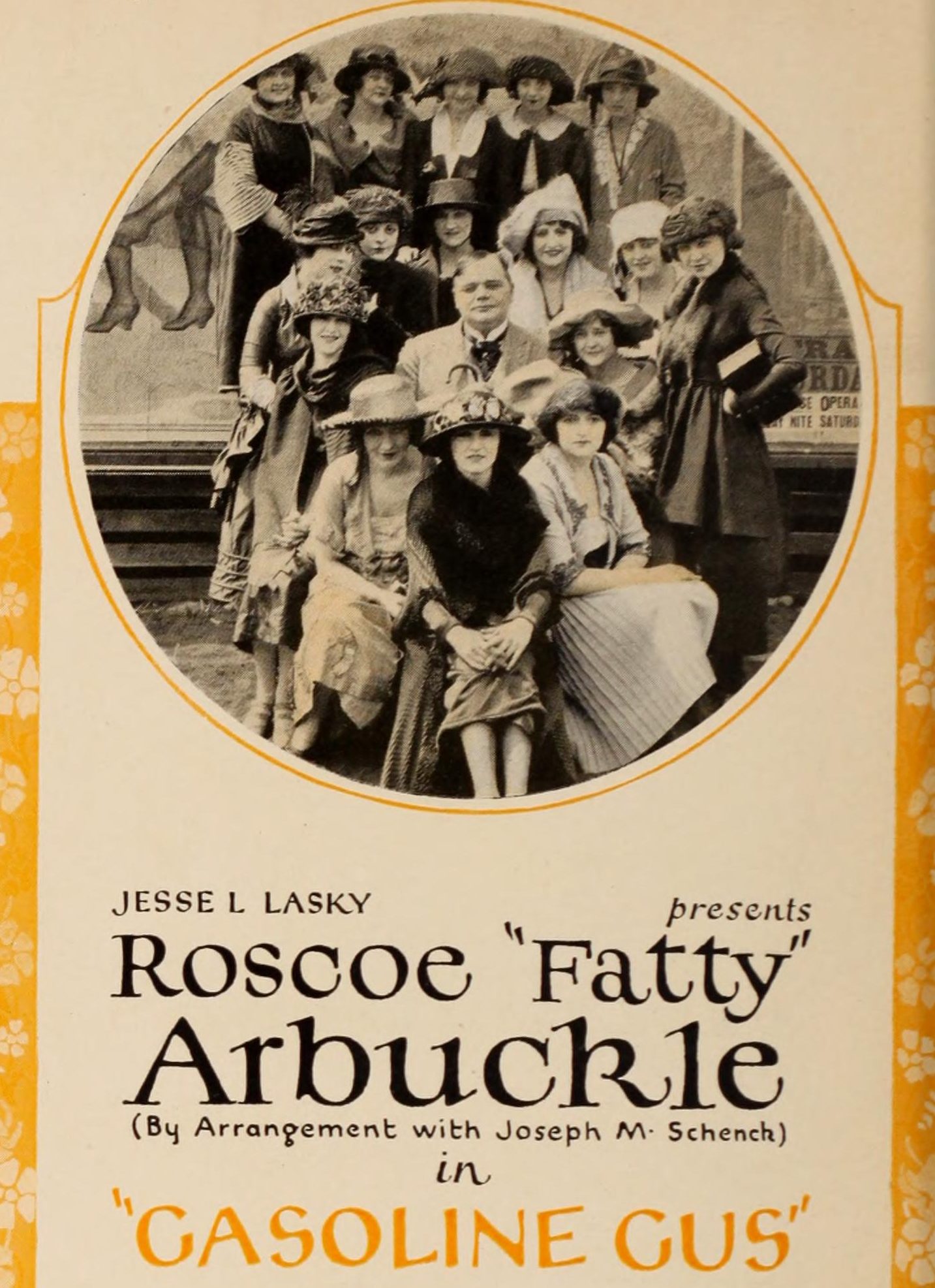

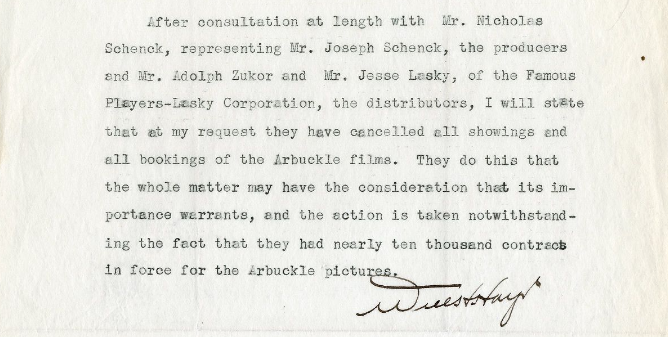

Roscoe Arbuckle was still in production on location from Chicago to Burbank to Los Angeles for his boxcar-bound adventure titled Freight Prepaid (1922) in July and August. At some point in his busy schedule, he sat down with the journalist Adela Rogers St. Johns for a feature interview. “Love Confession of a Fat Man,” published in the September 1921 issue of Photoplay had been timed to appear during Paramount Week, the second week of September, when Arbuckle’s latest comedy, Gasoline Gus (1921) would be released. Lila Lee was his leading lady in that film as well as in Freight Prepaid, which included a scene in which he and Lee would get married before a minister.[1] Marriage, too, had been a theme of another recent production, Should a Man Marry?, which he retitled This Is So Sudden (unreleased). Crazy to Marry (1921) would release at the end of August, premiering at Grauman’s Million Dollar Theater. Such an interview would certainly make good press, in promoting Arbuckle’s trilogy of marriage-themed movies and feeding speculation about his reported marital prospects, but also distract his audience from some recent unwanted attention.

A cloud of opprobrium had gathered over the moral and monetary excesses of movie moguls and the film colony. Four years earlier in March 1917, following a dinner given in Arbuckle’s honor—for having signed his first $1 million contract—at Boston’s Copley Plaza Hotel, Adolph Zukor. Jesse Lasky, Hiram Abrams, and other Paramount executives quit the hotel for the Mishawum Manor, an elegant roadhouse and brothel in the suburb of Woburn, Massachusetts. There, from midnight on, Zukor and his associates ate fried chicken, drank champagne, and bedded the Manor’s pretty young prostitutes. Soon after, the late night frolic was exposed when the husbands of some of the women complained to the Boston DA Nathan Tufts. A meeting between Tufts and the moguls was called and $100,000 in hush money was settled on. The story stayed hushed until July 1921 when a scandal erupted around Tufts over the payoff, a case that ultimately reached the Supreme Court of Massachusetts. Because Zukor and others, with their names and money, fed the prejudices of anti-Semitic readers, who believed such wealthy Jewish men were little more than white slavers, the story was heavily reported in American newspapers in July and August and usually referenced the Arbuckle dinner. At the time, Famous Players-Lasky issued press releases to declare that the comedian had not attended the afterparty event and had no part in the debauch that followed.

Though until that moment Arbuckle had been the avatar of “good clean” comedies for Paramount, he didn’t help himself in Chicago during the third week of July, while filming exteriors for Freight Prepaid. Initial accounts reported that Arbuckle, on July 20, had “engaged” Joe Greenberg, a young bellboy at the Congress Hotel, “to do some work for him but they could not agree on the wage. Words, as is the movie custom, were followed by blows. The bell boy got the worst of it.”[2] Arbuckle had struck Greenberg in the eye and the latter reported the assault to the police. The comedian was charged with disorderly conduct and posted bond for $50 but forfeited it when he failed to appear in court.

Louella Parsons, in her August 8 column, described the altercation as involving a waiter rather than a bellboy. A month later, as incidents from Arbuckle’s past surfaced in the press following the death of Virginia Rappe, the waiter variation was reported in detail. Arbuckle and a small party that included his director for Fast Freight, James Cruze, were having lunch in the Congress Hotel while a waiter named Joe Greenberg served sandwiches. “For the delectation of all, ‘Fatty’ took a club sandwich and flattened it on his [the waiter’s] head.[3] Greenberg responded by saying, “Mr. Arbuckle, you’re the funniest man I ever saw!” Arbuckle, perhaps detecting sarcasm, tossed the sandwich at Greenberg and missed. Then, finally, the comedian tossed a platter of creamed chicken in the waiter’s face. Greenberg, dripping creamed chicken, returned with two Chicago police officers who took Arbuckle to the Clark Street Station.

The Mishawum Manor incident and Arbuckle’s reckless Jekyll-and-Hyde behavior at the Congress Hotel should have been defused by St. Johns’ interview. It was an opportunity to show that he was mature and thoughtful rather than an obese man-child, urbane rather than banal, and the like, anything to come out from under the shadow of his “Fatty” persona. Perhaps most importantly, Arbuckle would emerge decidedly straight. Although he wasn’t a known homosexual, his interview seems intended to create an image of an eligible bachelor for the fawning public, much the way gay actors in that era would allow the studios’ publicity departments to remake their public images to suit broad public tastes.

Unlike the Dorothy Wallace rumor, for which he may have been the source himself, in Photoplay he could telegraph his current or future availability to the right woman. St. Johns too, let Arbuckle’s slough off the persona of “Fatty” a little more. This had been going on for a long time, indeed from childhood when he was the victim of body shaming. In a 1917 interview, the author noted Arbuckle’s body language, that when Arbuckle sat down, “he achieved the apparently impossible

by crossing one leg over the other knee. And every time he got up and sat down, he did it again. Each time I saw the performance beginning I secretly bet with myself that he couldn’t make it, but I always lost. It was an acrobatic triumph. But it was also a side-light on his character. For if there is one thing Roscoe Arbuckle has made up his mind about it is that he won’t be the ordinary fat man. He won’t sit like a fat man. He won’t dress like a fat man. And, above all, he won’t depend on his diameter and phenomenal circumference to make people laugh. When he is out of the movies, he looks like a modern Beau Brummel under a magnifying glass.[4]

Arbuckle was no less body conscious than a Hollywood actress, than Virginia Rappe. But that wasn’t the real point of his “Love Confessions.” He seemed to be imparting that he wasn’t “Fatty” but rather an actor no less a sex object than, say, Lowell Sherman, one of his new friends, and other debonairs of the silent era. The message that Arbuckle and St. Johns conveyed was this: How could any woman in her right mind say no to such a gentle man and gentleman? Especially one single again. There was no mention of a wife, of Minta Durfee.

St. Johns was an insider so likely respected the distance between married performers who are professionally distinct from each other, which kept Durfee out of the picture. But in the public mind, to do so only confirmed what people read in the popular movie magazine Photoplay, in its Questions & Answers column in May and in November issues that Arbuckle “is divorced from Minta Durfee.”[5]

How much of the “Love Confessions” is Arbuckle’s and how much is invented by St. Johns isn’t difficult to discern. If one compares it to other interviews he had given in the past, Arbuckle appears to have been a candid and cooperative subject, in contrast to the silence forced on him by his lawyers just a few weeks later when Virginia Rappe was dead and he stood accused of her murder. Having gone to press, the interview couldn’t be pulled. Surely Photoplay’s publisher, James Quirk, apprehended how Arbuckle’s making himself out to be a lady killer looked in print and with his estranged wife, Minta Durfee, on her way to be at her husband’s side. And St. Johns had to mention the same purple bathrobe, silk pajamas, and impressive bedroom slippers that Arbuckle wore for his interview and wore when he greeted Virginia Rappe in room 1220 of the St. Francis Hotel. The interview, too, takes place during one of Arbuckle’s big catered lunches.

Despite Arbuckle’s careless disregard for himself and the poor timing of this admiring profile, St. Johns became one of Arbuckle’s staunchest defenders—and the most acerbic character assassins of Virginia Rappe. Her memoirs, written a half century later, still suggest a certain malice for the dead woman as though it were her fault that Arbuckle’s openness and candor and the way it had been so lovingly framed, tiptoeing around Minta Durfee, whom St. Johns knew, had been spoiled. “Virginia Rappe,” she wrote, “got some alcohol in her system, stripped off her clothes, and plunged Fatty and Hollywood into our first major scandal.”[6]

Love Confessions of a Fat Man[7]

“Nobody loves a fat man except a temperamental woman.” Thus spake Roscoe in deep and solemn tones—have you ever noticed how much funnier Roscoe is when he’s solemn than he is when he’s funny?—and girded himself about with the folds of a purple velvet dressing gown. One foot, encased in a large but sightly bath slipper (my, how intimate this story is beginning to sound!) actually tapped the floor in emphasis and encouragement.

“Consequently, since women are getting more temperamental every day, I predict—I prophesy—that the fat man is about to have his day. He will be sought, chased, even mobbed, because there will not be enough of him to go round—not individually, but as an institution.

“Like the shrinking violet have we languished for lo, these many years, but we are about to come into our own and maybe a little bit of the other fellow’s. I feel that I was born at the auspicious moment for a fat man.”

Having satisfactorily outlined his policy, Fatty leaned back in his chair and encompassed me with that isn’t-it-a-grand-old-world smile of his.

We were lunching together in his bedroom. I shall never be able to estimate just what percentage of effect they had on me—those pongee pajamas. Of course, I had seen men in pajamas before. If you read the ads in the magazines you can’t help but see men in and out of most anything. But I’d never interviewed in them before.

And I love pongee pajamas. I suppose it is only fair to my husband to state that the bedroom was a set—on stage three, at the Lasky studio. That the pajamas and the dressing gown and even the bath slippers were only his costume for a scene and that we were almost aggressively chaperoned by seventeen stage carpenters, thirteen electricians, a few stray cameramen, and a troop of studio cats.

And Oscar. The colored gentleman that “tends to” Mr. Arbuckle.

Nevertheless, those pongee pajamas were exceedingly—intrigante, if you understand French.

That is to say, one really can’t talk to a man in his pajamas without feeling more or less—well, sympathetic and well-acquainted, so I may have taken too lenient a view of his view for a confessor.

“Woman?” asked Roscoe, when I delicately broached the subject of my visit. “Woman! Lovely woman—in our hours of ease uncertain, coy and hard to please! Somebody certainly wrote that. Well, well, I appreciate the compliment you pay me. I am not an expert on the ladies. I have watched a lot of these he-vamps talk themselves into a love affair—and then talk themselves out. But personally, I am not an expert.

“The only thing a man never regrets saying about a woman is nothing.”

I couldn’t tell him the real reason that I had suddenly decided to be a mother confessor to him and gather all his ideas about women. It was at once too flattering and too unflattering.

Because—by jove, he may be right when he says the fat man is just beginning to come into his own—because Roscoe in the role of a matinee idol had dawned upon my startled senses only two days before. Up to that time I regarded him merely as a comedian. Then I overheard a couple of school girls—of the cut-his-picture-out-and-sleep-with-it-under-the pillow age—discussing motion picture males. After admitting that Wally Reid was undoubtedly the handsomest man in the world and that they were in love with Tommie Meighan—one girl said, “But I just adore Roscoe Arbuckle. Isn’t he sweet? And mother says it’s the wisest thing now to pick out a good-natured man. Everything is so expensive.”

I roared internally. Later I repeated this to a friend of mine—a clever, red-headed young female with as much temperament as a World Series southpaw.

I hope Mr. Arbuckle will understand and forgive me when I say I added something facetious about anybody loving a fat man. You’ve probably heard that yourself.

My red-headed friend gave me a most unfriendly stare. “I’m sure I don’t see anything funny in that,” she said, in a voice that would have opened a can. “I think Roscoe Arbuckle is one of the loveliest men on the screen. Just think how—how restful, and simple, it would be, to be in love with a man like that. He’s the kindest man, too. always doing something for somebody.”

So I began to give Roscoe some consideration. I began thinking of his screen love affairs—they’re the only ones I’m allowed to think of—the charming, obliging, devoted, good-natured creature he had made of his funny, fat lovers. And I trotted around to ask him what he actually thought about it all.

“Where did you get the notion I knew anything about women?” he asked, as Oscar appeared with a large tray of varied viands.

“Well, everybody must have some ideas about everything,” I said.

“Oh, not necessarily,” said Fatty, examining the contents of the tray. “Look at Congress.”

“Haven’t you any ideas about women,” I asked, looking him firmly in the eye.

He grinned. “Some,” he admitted. “Oh, yes, several.”

“Then go on and tell me.”

“Maybe the women won’t like ‘em,” he murmured, stirring the gravy around his roast beef sandwich.

“Are you afraid of women?” I asked lightly. “You bet I am. You just bet I am. So is everybody else that wears pants on the outside in this land of the free and home of the brave. Women are the free and we are the brave. The 19th amendment is only the hors d’oeuvre to the amendments they will pass now they have found out they can. I expect pretty soon the only reason they allow us around will be to prevent race suicide. Doggone, I sure like ‘em but I sure fear ‘em. “Now I want you to understand that anything I may say in the heat of oratory is speculation pure and simple. I don’t know any more about women than an Armenian knows about pate de fois gras.[8] Women alone are sufficiently mysterious to me to make me feel like Watson without the needle—and as for wives, they are a separate race of human.

“I admit I’m wrong before I start, so please don’t let anybody argue with me.

“As I was saying, I am convinced that the fat man as a lover is going to be the best seller on the market for the next few years. He is coming into his kingdom at last. He may never bring as high prices or display as fancy goods as these he-vamps and cavemen and Don Juans, but as a good, reliable, all the year around line of goods, he’s going to have it on them all.

“Temperamental women haven’t enough padding on their own nerves, so they’re going to choose a fellow that they think has enough for both of them.

“Women are getting more temperamental every day. The audiences are bigger, that’s all.

“A woman today has got to have a good natured-husband. Statistics show that there have been more love murders, marriage murders and suicide love pacts in the last few years than ever before in the history of the world.

“It is very hard either to murder or to be murdered by a fat man.

“When you think of the things a woman wants to do nowadays and the things she does not want you to do—the percentage is surprisingly low, seeing there aren’t fat men enough to go around. Women want to smoke cigarettes, bob their hair, drink wood alcohol, have men friends, spend their own and everybody else’s money, cut their skirts off just above the knees, run their own and your business, drive automobiles, go to conventions, elect mayors and presidents and be as independent as the Kaiser thought he was. The only thing she can’t get along without is her lipstick. She’s just got to have a good-natured husband. You can see that for yourself.

“And one that can be a father to her children, because she’s going to be pretty busy and she may not have much time to [be a wife].[9]

“Now a fat man can certainly stand more emotional excitement than most men. It has farther to go before it hits any vulnerable point. Scenes, thrills, bills, and various other manifestations of the genus temperamentus feminus rebound from him with alacrity.

“In fact, it’s all rather good for him. And temperamentalism is not good for most men. It frays their nerves and upsets their digestion and disrupts their business.

“A fat man has no nerves, no digestion and no business. At least, if he has they need fraying, upsetting and disrupting.

“Some people think fat men may be handsome. I shouldn’t like to be quoted on that point.

“But anyway, with all she’s got to look after, woman today cannot be bothered with all the grief and agony and care that comes from having a handsome husband running about. He takes too much looking after. A husband—an ordinary husband, requires as much looking after as a child. A handsome husband is like having twins. So she prefers somebody that, when she tucks him in at night and says, “Don’t stay awake, dearie, I may be late,” won’t sneak out and go sleep-walking around the adjoining roofs. Fat men love to sleep. It’s safe to leave ‘em.

“Nothing is so humiliating to an efficient woman these days as an unfaithful husband. Fat men are inclined to be faithful. It’s often a form of laziness, you know. Woman used to be proud of having a Greek God of her own. But competition is so keen since the war she’d rather accept a good, fat guarantee of fidelity and engrave on her crest the motto ‘Beauty is only skin deep.’

“A smart woman wants a husband that will be a husband and stay a husband without too much protest.

“A fat man is a sentimental idiot as a general thing, filled with old-fashioned ideas about home, honor and marriages made in heaven. And since marriage is a secondary consideration to the woman of today who has equal rights with a man, she will pass up the spinal thrills for untroubled domesticity.

“Ever hear the old line about ‘Love is of man’s life a thing apart, ‘tis woman’s whole existence’?

“Bunk. Absolute bunk. Love isn’t the entire existence of the female of the species in this year A.D.

“But a fat man doesn’t mind that so much. He likes to be let alone a good deal. He can stand a modern wife who has as many interests as he has outside the home. It makes her lot easier to live with if she has something to think about and pick on besides him.

“A fat man is usually brave. He’s had to be. It takes a brave man to marry the modern woman. She knows so much. It takes a brave man to marry at all. You walk into the church because some girl wants you to, and the first thing you know you’re all messed up with posterity and responsible for the sins of your grandchildren.

“However, I believe in marriage. Life cannot be all sunshine.

“But I’m not sure as to love. Marriage would be safer without love.

“If you fall in love, nothing does you any good. It’s fatal. I don ‘t care if you know as much about women as Lew Cody says he does, if you really fall for one of them you’re gone; take your choice between chloroform and the river.

“Why, if you don’t care so awfully much about a girl you show some sense. Instead of treating her nice and jumping around like a trick duck, you can ignore her. Treat her with superb indifference. Display your best traits. But not for her.

“Of course, any man ought to be capable of falling mildly in love with every pretty woman he sees. But be reasonable. Love a little and a little while. Find a happy medium.

“My only requirements for a woman are that she be smart, well-dressed and have a lot of pep. I can get along without the blonde curls if they’re apt to get tangled in her fan belt. She ought to be a good fellow. Never pick on a fellow because he’s a man’s man. If he’s got to wander around when they go out together and smoke and talk, it’s an innocent diversion. There are a lot worse.

“She doesn’t have to be pretty. I can look at the scenery most anywhere from the Hudson to the Golden Gate. And I can contemplate strings of pearls in any jewelry window. If she’s smiling and well dressed, she’s decorative enough for me.

“Every man starts life with a preconceived notion about women. And love and matrimony. Every man, and nine out of ten are cut off the same piece.

“A man’s ideal is most of the things most men want to come home to—slippers, drawn curtains, a bright fire, peace, praise, comfort, and a good, hot dinner. He may take his romance with a dash of bitters, but he wants his matrimonial dreams padded so the sharp corners won’t cut.

“Pretty soon he adjusts that viewpoint. Or some woman adjusts it for him.

“Now a fat man soon finds he needs somebody with a little more pep. He and a girl that’s so full of pep she acts like a dynamo will strike a good average. He needs a stimulant, not a sedative. Whereas most men actually crave a bromide for a wife instead of a riot.

“I wouldn’t marry the most beautiful woman in the world if she asked me. A beautiful wife is like a diamond necklace, nice to have but a lot of bother to take care of.

“You want a woman with pride in herself, who will keep pace with you. A fat man isn’t exacting about details. He doesn’t care whether his wife gets up to breakfast with him or not. I’d rather she didn’t. I don’t want to see anybody at breakfast. I want to be let alone, with my eggs and my paper. I’ll bet you more quarrels start at the breakfast table than any other time.

“If she’ll be up for dinner, bright and fresh and ready to cheer me on, I’ll be satisfied. I like intelligent conversation. Not too highbrow—talking to some women is like trying to fly across the Atlantic in an aeroplane. Ten to one you won’t make it, and if you do you wish you hadn’t.

“The Turkish men are the most particular in the world—they can afford to be. And they prefer fat women.

“That’s why I believe the American women, who are the most particular in the world, are coming to appreciate the advantages of fat men.

“Haven’t you noticed what pretty girls I cop in the pictures?”

He began to shake all over with a big, jolly laugh.

“But you know, I have very high ideals about women. I understand—the best side of them sometimes. I like nice girls.”

I just looked at him. “But you don’t deserve any penance,” I said. “You could confess all that on the porch of the Hollywood Hotel and not be gossiped about. I’ll have to absolve you right away.”

“That,” said he, with a complacent smile, “is because I’m fat.

[1] Edwin Schallert, “Sad Smile Is Comedy’s Style: Lila Lee Uses Hers to Win Gallant Arbuckle,” Los Angeles Times, 31 July 1921, III:1.

[2] “Fatty Blacks a Boy’s Eye,” Boston Post, 21 July 1921, 11.

[3] From “Fatty’s History Is Spectacular,” Los Angeles Examiner, 11 September 1921, https://www.silentera.com/taylorology/issues/Taylor28.txt.

[4] From Literary Digest, 14 July 1917, https://www.silentera.com/taylorology/issues/Taylor28.txt.

[5] “Questions & Answers,” Photoplay, April 1921, 113; Photoplay, November 1921, 107.

[6] Adela Rogers St. Johns, Love, Laughter and Tears: My Hollywood Story (New York: Doubleday, 1978), 59.

[7] Roscoe Arbuckle, “Love Confessions of a Fat Man as told to Adela Rogers St. Johns, Photoplay, September 1921, 22–23, 102.

[8] This tactless joke on the part of Arbuckle alludes to images of starving Armenian refugees, victims of Ottoman Turks during the First World War.

[9] The original article is split between pages 23 and 102. Missing text inferred.