No celluloid will ever show the like of it or scenario tell the equal of it. It is Fatty’s masterpiece.

—Freda Blum

On the morning Roscoe Arbuckle was to testify, November 28, 1921, it was rumored that an unidentified attorney threatened to quit the comedian’s “million-dollar defense” team. According to the Los Angeles Express, this was Milton Cohen, angered over the lead defense attorney, Gavin McNab, mulling the idea that it might be better not to have the defendant testify. Chandler Sprague in the San Francisco Examiner reported one possible reason for McNab’s hesitation: that “certain business interests were adverse” to the comedian testifying, a veiled reference to one man, surely, Adolph Zukor, who was hardly as sanguine about Arbuckle making a comeback as his manager and chief fund raiser for his defense, Joseph Schenck, and the man assigned to watch his clients in Hollywood, Lou Anger.

There was also dissension on the prosecution’s side. Milton U’Ren, a veteran assistant district attorney, had been passed over to lead the cross-examination of Arbuckle. He was angry enough to resign from the case as well, a case that he had largely developed with the approval of District Attorney Matthew Brady. During the noon recess, U’Ren could be heard arguing with Brady in the Hall of Justice because his fellow prosecutor, Leo Friedman, had hardly made a dent in Arbuckle.

Most reporters expected the comedian to do well and eclipse anything thus far said from the witness chair. Otis M. Wiles for the Los Angeles Times used a slapstick term for the comedian’s impending appearance as a “climax stunt.” Early into his cross-examination, Arbuckle impressed most of the reporters who saw and heard him. Who they were rooting for, too, was evident in their copy. According to Bart Haley of Philadelphia’s Evening Public Ledger, Arbuckle

revealed himself in his narrative as the most piteous of fat men, the most tragically used of all good Samaritans, an amiable individual whose rooms were invaded by uninvited guests, who ate his food and borrowed his motorcar, and ran up a big bill on him and got him into a pit of trouble with the hotel management before they finally started him on the way to jail under a charge of murder.[1]

Earl Ennis of the San Francisco Bulletin seemed to applaud Arbuckle as well. But he also touched on what the monitors of the Women’s Vigilant Committee—and Zukor as well—knew would be hard to square. “There was nothing nice about Arbuckle’s story—noting elevating,” Ennis wrote, “It was a ‘booze party,’ pure and simple with jumbled elements involved—salesmen, movie stars, women, all scrambled unconventionally into an afternoon’s entertainment.”[2]

What follows is a revised version of our “provisional” transcript of Arbuckle’s testimony, which is likely the most complete version available since no state transcript has been preserved or discovered. For the most part, it is based on four San Francisco dailies—the Bulletin, Call, Chronicle, and Examiner—which employed their own stenographers.

Most of the reporters covering the trial believed that Arbuckle had secured his acquittal. As it turned out, at least two jurors were unconvinced and saw Arbuckle as an actor playing a role. Indeed, the testimony reads as if it were tailored or, to use the language of the cinema, a recut of previous testimony by other witnesses to fit the image of a gentler Good Samaritan Arbuckle that would befit the public image of “Fatty.” This includes his original statement issued on the night of September 9, 1921, the day Virginia Rappe died, and published the next day in the morning Los Angeles Times. That statement, which was vetted by Arbuckle’s original lead attorney, Frank Dominguez, only states that “After Miss Rappe had a couple of drinks she became hysterical and I called the hotel physician and the manager.” In its place, however, Arbuckle posits a much expanded series of events.

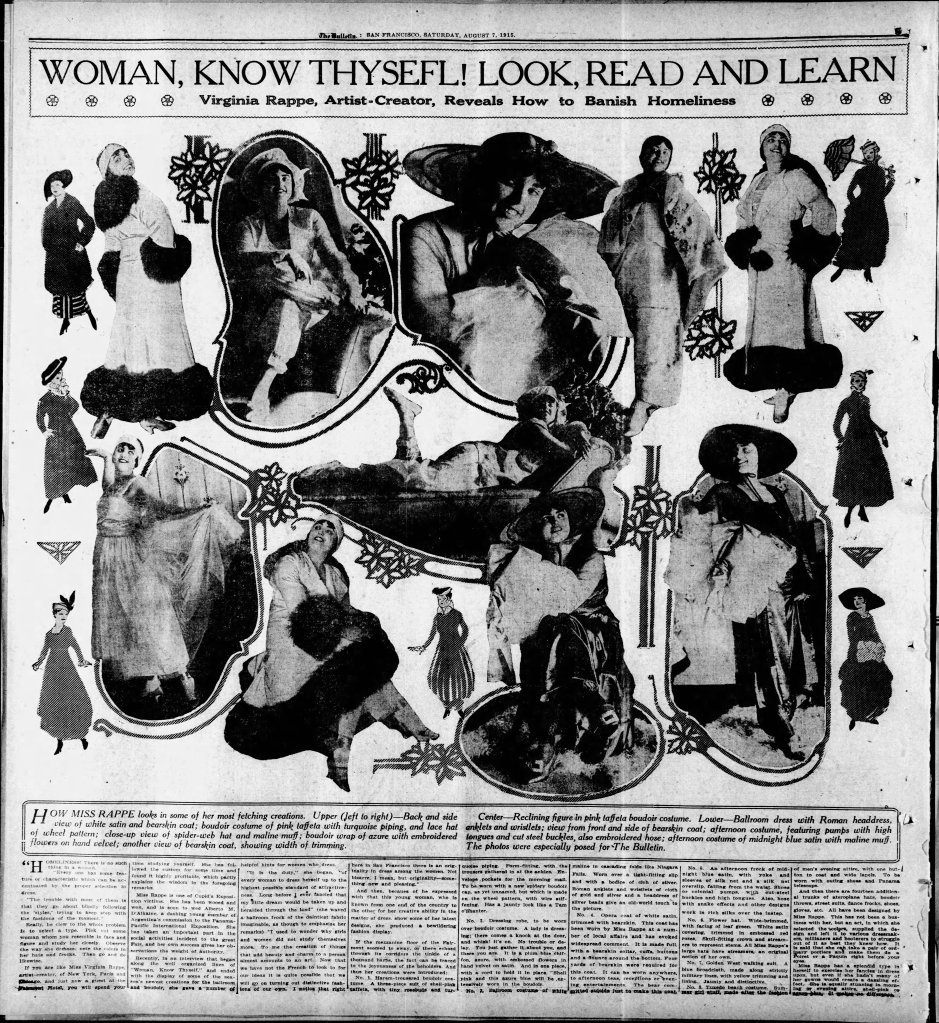

Traces of the real Virginia Rappe emerge here and there in the testimony. There was even a moment of unintended silence just before the noon recess, when Deputy Coroner Jane Walsh entered the courtroom, carrying Rappe’s bladder, preserved in a glass jar and placed on the evidence table. But in Arbuckle’s account of September 5, 1921, Rappe remains a cipher, a poseable doll even before she is found on the bathroom floor. The comedian is very careful to avoid how well he knew Rappe. They had a certain rapport. But here the comedian quite literally turns his back on her the moment she made her way to his bedroom. This way, he can assert that he was unaware that she was there when he entered to get dressed in order to go “riding” with the other woman in his story, Mae Taube.

Though Arbuckle’s testimony is ductile, that fits and twists and conforms to what really happened in room 1219, it suggests to us that the injury that was inflicted on Rappe took place in the bathroom and even has the outlines of sexual imposition. Laws had been on the books for decades in regard to the temptations of hotel and furnished room accommodations as dens of lasciviousness, fornication, and adultery. But for casual sex during a party in a smallish three-room hotel suite, the privacy for such intimacies (and immediacies) could be found in the bathrooms. If there was a sexual encounter that preceded or led to the injury, the bathroom would have provided a space with greater privacy and sound dampening, not to mention conveniently located fixtures such as a sink, a toilet, and towel rods for grab irons, as well as the hard surfaces on which to brace oneself. The brass bedsteads in room 1219, shown in E. O. Heinrich’s photographs, could also serve this purpose. But Arbuckle, much as he was proud to cross his leg, likely could do it Venus observa.

What was termed an “official transcript” lacked much of Arbuckle’s real “voice” dismissing Friedman’s skepticism and often making him Fatty’s straight man. But the seeming frustration and incompetence seen in the youngest member of the prosecution is exaggerated. Friedman’s approach likely relied on the jury’s perception of subtleties in Arbuckle’s testimony that reveal it to be rehearsed, coached, and a piece of fiction. We also see places where Friedman should have probed more deeply, such as Arbuckle’s making his friend and roommate at the St. Francis Hotel, the comedy director Fred Fishback, a patsy for the liquor and inviting Rappe at the behest of his friend, Ira Fortlouis, a San Francisco gown salesman, the latter being mysteriously expelled from the party at the time of Rappe’s crisis.

It was Fortlouis’s sighting of—or rather attraction to—Rappe that resulted in her invitation to Arbuckle’s suite. Did Fortlouis pay so much attention to her that Arbuckle saw a rival to his own attentions to Rappe? And why did Friedman not ask about the vomit? It seems as though Rappe vomited copiously and it’s unlikely all of it would have gone down the toilet, yet that word is absent in all the other testimonies. In the testimony of party guests Zey Prevost and Alice Blake, the back of Arbuckle’s pajamas is visibly wet. The double bed in which Rappe was wet. But nothing was asked about the source of the wetness, as though it were a taboo subject. One must wonder if there was a code among newspaper editors that prevented them from reporting specific details. (Interestingly, the prosecution’s criminologist E. O. Heinrich reported on old semen stains he found on the mattress pads and bedclothes, but these had already gone through the laundry and could have come from other guests. For this reason, Milton U’Ren elected to pursue only the fingerprint evidence and the marks left by the French heels of Maude Delmont’s kicking the door—which Arbuckle said that he didn’t hear.)

The same might be asked about the defense attorneys who failed to subpoena May Taube. She was possibly Arbuckle’s only close friend at the hotel that day. She was seen by other party guests in the early afternoon, as Arbuckle’s testimony states. But in her one statement to the District Attorney, she left because she didn’t know anyone there, which refers to the women and with the implication that they were low by her standards. Friedman does establish that Arbuckle introduced Taube to one of these women, indeed, Virginia Rappe. But that is as far as he takes it, leaving it to the jury and us to see if there was a “woman scorned.”

Taube could have easily corroborated the story Arbuckle tells in the following transcript. She would also have been a perfect character witness. Although she didn’t go “riding” with Arbuckle on Labor Day afternoon, Mrs. Taube spent the night of September 5 dancing with him in the St. Francis ballroom according to her statement to the DA. But she is never called in any of the three Arbuckle trials. That she was that untouchable suggests she held a certain leverage. (See our Taube entry for more information about her.)

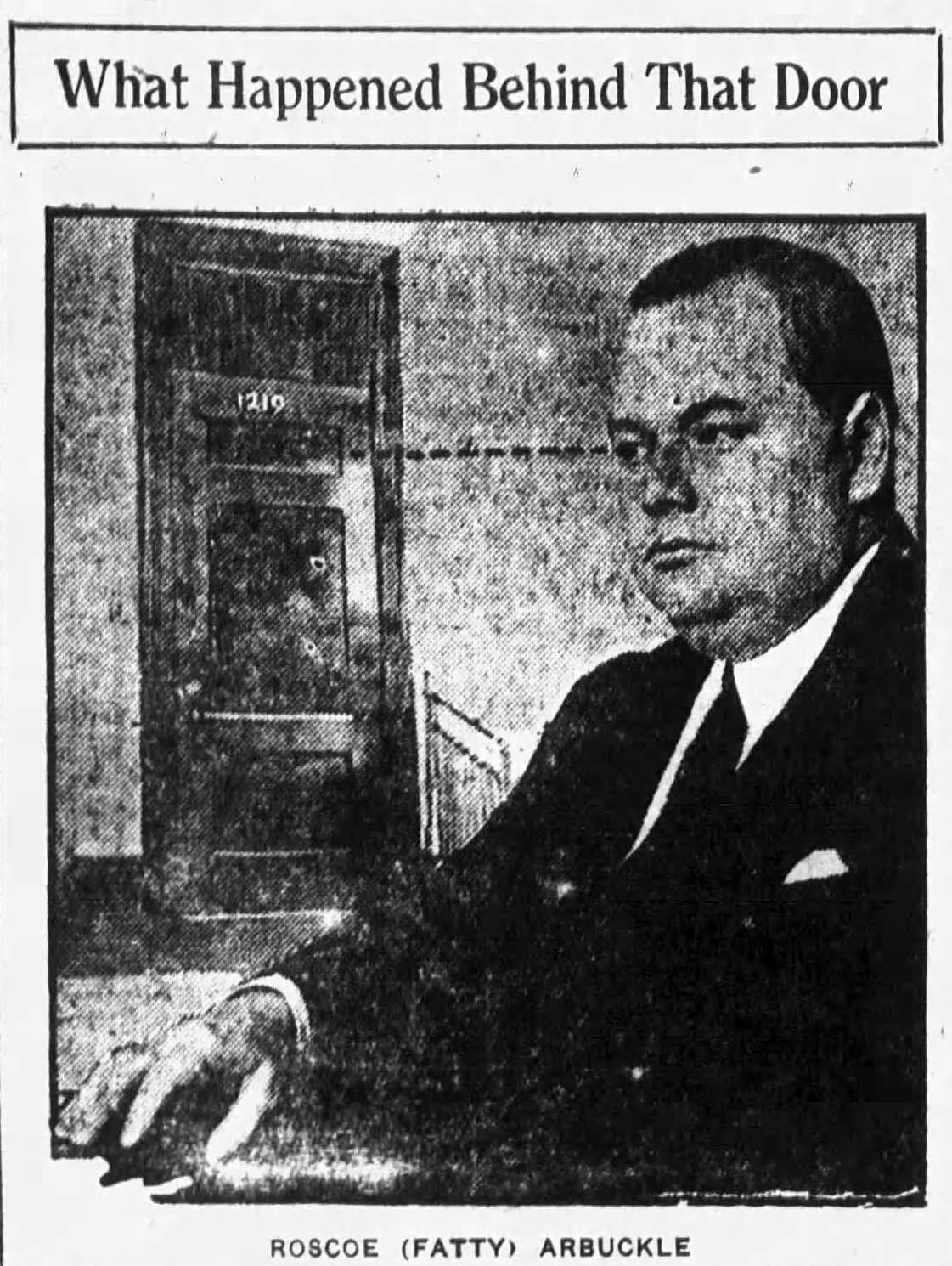

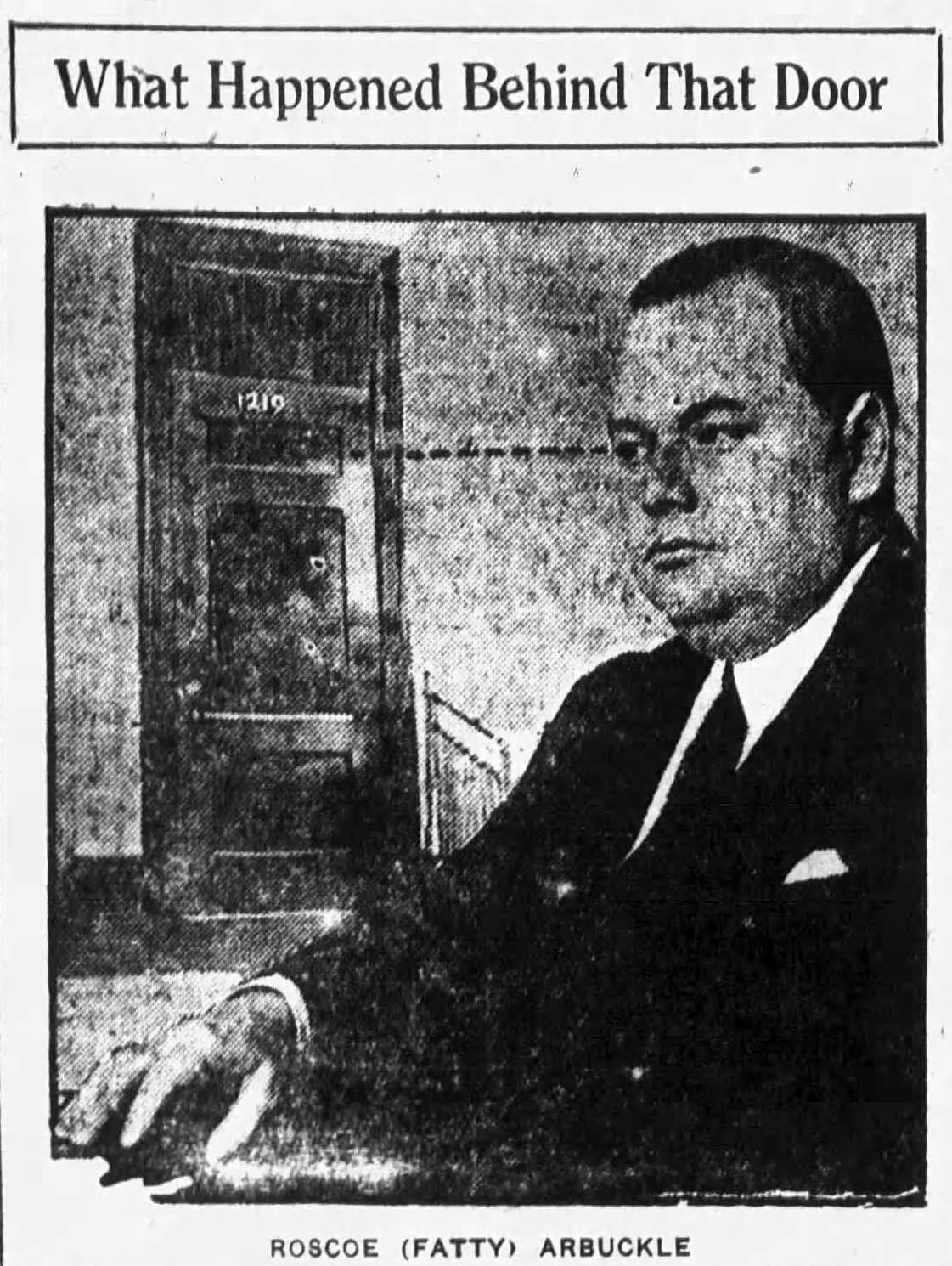

Satirical photograph published in the Modesto Evening News, November 28, 1921 (Newspapers.com)

Satirical photograph published in the Modesto Evening News, November 28, 1921 (Newspapers.com)

[1] Bart Haley, “Fatty, Cool on the Stand, Recites New Version of Miss Rappe’s Hurt,” Evening Public Ledger, 29 November 1921, 1.

[2] Earl Ennis, “Crowded Court Listens Tensely as Actor Tells Details of Tragic Party,” San Francisco Bulletin, 28 November 1921, FS1.

Arbuckle: My name is Roscoe Arbuckle. I am a movie actor. [. . .]

McNab: Mr. Arbuckle, where were you on September 5 of this year?

A: At the St Francis Hotel.

Q: What rooms did you occupy at the St. Francis Hotel?

A. 1219, 1220 and 1221.

Q: Did you see Virginia Rappe on that day.

A: Yes, sir.

Q: At what time, and where?

A: She came into 1220 about 12 o’clock, I should judge.

Q: That is 1220, your room at the St, Francis Hotel?

A: Yes, sir.

Q. Who were there when she came?

A: Mr. Fortlouis, Mr. Sherman, Mr. Fischbach[1] and myself.

Q: Did Miss Rappe come to those rooms by your invitation?

A: No, sir.

Q: Who, if anybody, joined your party?[2]

A. A few minutes —

Q: Joined the company in your rooms?

A: A few minutes after Miss Rappe came in Mrs. Delmont came in.

Q: Dd you know Mrs. Delmont previous to that time?

A: No, sir.

Q: Was Mrs. Delmont there by your invitation?

A: No.

Q: Who else came in, if anybody?

A: Miss Blake came in.

Q: Did Miss Blake come there by your invitation?

A: No, sir.

Q: Anybody else come?

A: Yes, Miss Prevost came later.

Q: Did Miss Prevost come by your invitation?

A: No, sir.

Q: Anybody else come?

A: Mr. Semnacher came in.

Q: Did Mr. Semnacher come by your invitation?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did anybody else come?

A: Yes, sir, Mrs. Taube and another lady.[3]

Q: Did Mrs. Taube come by your invitation?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: How were you dressed on that occasion?

A: I was dressed in pajamas and bathrobe and slippers.

Q: I will ask you if this is the bathrobe that you wore on that occasion (showing bathrobe to witness).

A: Yes, sir, my robe, yes, sir.

Q: I will ask the ladies and gentlemen of the jury to look at this; this has been much commented on in evidence.

Q: Did you at any time during that day see Miss Virginia Rappe in room 1219?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: About what time.

A: Around 3 o’clock.

Q: How do you know it was about 3 o’clock?

A: I looked at the clock; I was going out.

Q: And what fixes—what caused you to look at the clock at that time?

A: I had an engagement with Mrs. Taube, and she came up about 1:30, but I had loaned Mr. Fischbach my car and she said she would wait downstairs until he came back; and he said he was going to the beach and he would come back just as soon as he could, so I figured it was about time for him to come back, so I looked—

Mr. Friedman: Just a moment. We ask that everything after the words “I figured” be stricken out as a conclusion of the witness.

The Court: It goes out.[4]

Mr. McNab: Where, if any place, previous to seeing Miss Rappe in 1219, where last before had you seen her?

Arbuckle: In 1220; I saw her go into 1221.

Q: And when you entered—at what time did you enter 1219?

A: Just about 3 o’clock.

Q: At the time you entered 1219 was or not the door between 1219 and 1220 opened?

A: Yes, sir, it was open.

Q: Did you know at the time you entered 1219 that Miss Rappe was there?

Mr. Friedman: Now, that is objected to as calling for the conclusion of the witness, and as leading and suggestive. And upon the ground that the question has already been asked and answered.

Mr. McNab: I have not asked that, and the question is not leading.

The Court: Objection sustained.

Mr. McNab: Did your honor sustain the objection?

The Court: Sustained the objection.

Mr. McNab: At the time you entered 1219, I understand the door between 1219 and 1220 you state was open?

Arbuckle: Yes, sir.

Q: And where in 1219 did you see Miss Rappe?

A: I did not see her in 1219.

Q: Where did you see her?

A: I found her in the bathroom.

Q: Of what room?

A: Of 1219.

Q: And under what circumstances did you find her in the bathroom?

A: When I walked into 1219, I closed and locked the door, and went straight to the bathroom and found Miss Rappe on the floor holding her stomach and moving around on the floor. She had been vomiting [ill].[5]

Q: What did you do? Explain to the jury all the circumstances which occurred in the bathroom of 1219.

A: When I opened the door the door struck her, and I had to slide in this way (illustrating) to get in, to get by her and get hold of her. Then I closed the door and picked her up. When I picked her up, [I held her, and she was ill again]; I held her under the waist, like that (indicating), and by the forehead, to keep her hair back off her face.

Q: Then what else occurred? Give the jury all the circumstances occurring in the bathroom of 1219.

A: I took a towel and wiped her face, she was still sitting there holding her stomach, evidently in pain, and she asked for a drink of water.

Mr. Friedman: We ask that the words “evidently in pain” be stricken out.

Mr. McNab: It may go out.

Q: She asked for a drink of water, and I gave it to her, and she drank a glass of water, and she asked for another glass, and I gave it to her, and she drank another half a glass of water.

Q: What else happened?

A: I asked her if I could do anything for her. She said no, she would just like to lie down; so I lifted her into 1219 and sat her down on the small bed and she sat on the bed with her head toward the foot of the bed.

Q: What else did you do, if anything?

A: She just expressed a wish that she wanted to lie down; that she had these spells; that she wanted to lie down a while. I lifted her feet off the floor and put them on the bed; she was lying this way, with her feet off the bed, and I went into the bathroom and closed the door.

Q: What else happened when you left, the bathroom and returned to 1219, if anything?

A: I came back into 1219 in about—well, I was in there about two or three minutes, and I found Miss Rappe between the beds, rolling about on the floor, holding her stomach and crying and moaning, and I tried to pick her up, and I couldn’t get hold of her; I couldn’t get alongside of her to pick her up, so I pulled her up into a sitting position, then lifted her on to the large bed and stretched her out on the bed. She turned over on her left side (Arbuckle said Miss Rappe was taken ill again) and started to groan and I immediately went out of 1219 to find Mrs. Delmont.

Q: Whom did you find in 1220 when you went there?

A: Miss Prevost.

Q: Did you advise Miss Prevost of the condition of Miss Rappe?

A: Yes, I just said “Miss Rappe is sick.”

Q: Did Miss Prevost go into 1219 at that time?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: What else happened?

A: Just a few minutes after Mrs. Delmont came—not a few minutes, just may be a few seconds—Mrs. Delmont came out of 1221 and I told her and she went into 1219 and I followed behind her.

Q: What happened in 1219 then?

A: Miss Rappe was sitting up on the edge of the large bed, tearing her clothes in this fashion (illustrating), tearing and frothing at the mouth, like in a terrible temper, or something—

Mr. Friedman: We ask, of course, that the words “like in a terrible temper” be stricken out as a conclusion of the witness.

Mr. McNab: That may go out.

The Court: It goes out.

Mr. McNab: What else? Give the. jury a narrative of what occurred at that time in 1219.

Arbuckle: I say, she was sitting on the bed, tearing her clothes; she pulled her dress up, tore her stockings; she had a black lace garter, and she tore the lace off the garter. And Mr. Fischbach came in about that time and asked the girls to stop her tearing her clothes. And I went over to her, and she was tearing on the sleeve of her dress, and she one bad sleeve just hanging by a few shreds. I don’t know which one it was, and I says “All right, if you want that off I will take it off for you.” And I pulled it off for her; then I went out of the room.

Q: Did you return to the room later?

A: Yes, sir, some time later.

Q: What was occurring in the room at that time, when you returned?

A: Miss Rappe was then on the little bed nude.

Q: What occurred?

A: I went in there and Mrs. Delmont was rubbing her with some ice. She had a lot of ice in a towel or napkin, or something, and had it on the back of her neck, and she had another piece in her hand and was rubbing Miss Rappe with it. massaging her, and there was a piece of ice lying on Miss Rappe’s body. I picked it up and said, “What is this doing here?” She says, “Leave it here; I know how to take care of Virginia,” and I put it back on Miss Rappe when I picked it up and I started to cover Miss Rappe up, to pull the spread down from underneath her so I could cover her with it, and Mrs. Delmont told me to get out of the room and leave her alone, and I told Mrs. Delmont to shut up or I would throw her out of the window, and I went out of the room.

Q: What else occurred? Tell the jury what did you do? Anything further?

A: I went out of the room, and Mrs. Taube came in and I asked Mrs. Taube if she would phone Mr. Boyle, and we went into 1221, and Mrs. Taube picked up the phone and phoned Mr. Boyle and asked him to come up to the room and get a room for Miss Rappe.

Q: What occurred after that?

A. I went back into 1219 and told Mrs. Delmont to get dressed, that the manager was coming up, and she went out to get dressed, and she pulled the spread down underneath—from underneath Miss Rappe, down below, underneath her feet, and put it up over her, and went back into 1221.

Q: What further happened?

A: Mr. Boyle came in; he came to the door of 1221.

Q: What occurred thereafter?

A: I took him in to where Miss Rappe was lying in 1219.

Q: And what was done then?

A: Mrs. Delmont came in and we put a bathrobe on Miss Rappe, Mrs. Delmont and myself.[6]

Q: Where did you get the bathrobe?

A: Out of the closet; it was Mr. Fischbach’s robe.

Q: And what then was done?

A: We took her around through the hall into 1227.

Q: How did you get out of 1219?

A: Took her out of the door leading into the hall.

Q: Who opened the door?

A: Mr. Boyle.

Q: How did you get Miss Rappe around to 1227?

A: I carried her part of the way. She was limp and did not have any life in her body. She kept slipping, and I got about three-quarters of the way and I asked Mr. Boyle—I did not ask him to take her, I asked him to boost her up in the middle so I could get another hold of her, and he just took her right out of my arms and we went into 1227.

Q: Then what occurred in room 1227, if you know?

A: We put her to bed and covered her up, and I asked Mr. Boyle if he would get a doctor; and I walked back to the elevator with him and then I walked on into the room, into 1219.

Q: Was the door between 1219 and the hall unlocked throughout the day?

A: lt was, so far as I know. Mr. Fischbach went out that way.

Q: You saw him go out.

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And when you took Miss Rappe out, the door was open from the bedroom of 1219, was it?

Mr. Friedman: We object to the question as leading.

Mr. McNab: Well I withdraw it. How was the door open from 1219 into the hall?

Arbuckle: Mr. Boyle just walked over and opened it.

Q: Was or was not the window of room 1219 open that day?

A: lt was always open.

Friedman: Just a moment. We ask that the answer “always open” be stricken out.

Court: It goes out.

Arbuckle: lt was open.

McNab: How was the curtain of the window in room 1219?

Arbuckle: I raised the curtain myself in the morning when I arose.

Q: During the time that you were in room 1219, did you ever hear Miss Rappe say, “You hurt me” or “He hurt me”?

A: No, sir. I didn’t hear her say anything that could be understood.[7]

Q: Next day. September 6, or any other time, did you ever have any conversation at all with Mr. Semnacher about any incidents whatever regarding ice on Miss Rappe’s body?

A: Absolutely not.

Q: Did you ever—did you ever at any time, while in room 1219 of the St Francis Hotel, on September 5, 1921, have occasion to place the bottom of your hand over the hand of Miss Rappe, while her hand was resting against the door into the corridor, or did you do so?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did you at any time, while you were in room 1219 of the St. Francis Hotel, on September 5, 1921, come into contact in any way with the door leading into the corridor?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did you ever know a man by the name of Jesse Norgaard?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did you, during the month of August 1919, or at any other time, in Culver City, or at any other place, have the following conversation with Jesse Norgaard: You are supposed to have said to Mr. Norgaard, “Have you the key for Miss Rappe’s room?” and he is supposed to say. “Yes,” and then you are supposed to have said, “Let me have it; I want to play a joke on her.” And then Mr. Norgaard is supposed to have said, “No, sir, you cannot have it.” Then you are supposed to have said, “I will trade you this for the key,” and then you had a bunch of bills in your hand, supposed to have had a bunch of bills in your hand, consisting of two 20s and one 10 and other bills, too. Now, I will ask you if such a conversation, or any conversation like it, happened at the time and place between yourself and Mr. Norgaard?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did any such conversation occur between Mr. Norgaard and yourself, regardless of time and place?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did such a conversation, or anything like it, occur between yours self and any other person at any other time?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did any other circumstance occur in room 1219, of any kind, that you can tell this jury?

A: No, sir.

Q: You have narrated all the circumstances that occurred?

A: Absolutely all of the them.

Mr. McNab: That is all. Cross-examine the witness.

(Twenty-minute recess)

CROSS-EXAMINATION

Mr. Friedman: Now, you stated that you were residing at the St. Francis Hotel on the fifth of September, is that correct?

Arbuckle: Yes, sir.

Q: How many rooms did you have there?

A: Three rooms.

Q: Three, rooms?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And which of those rooms did you occupy?

A: I slept in the small bed in room 1219.

Q: And did anyone else occupy the room

A: Mr. Fischbach—we were there three nights. He occupied the room with me the first two nights.

Q: And the third night he didn’t occupy the room with you, is that correct?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Now, you stated that you never saw Mr. Norgaard at Culver City during August of 1919, or at any other time, is that correct?

A: I stated that I never had any conversation with Mr. Norgaard.

Q: Well, did you see him during the year 1919?

A: I cannot remember him.

Q: Now, where were you employed during August of 1919?

A: I had my own company.

Q: You had your own company, yes, but where?

A: At Culver City.

Q: At Culver City?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And you had a studio there?

A: No, sir.

Q: Were you using a studio?

A: I was renting a studio there.

Q: And from whom were yon renting the studio, if from anyone?

A: I had to work there, because I had to help finish paying for the studio, and that was the only way.

Q: You had to work where?

A: At Mr. Lehrman’s studio.

Q: Yes. then, during August of 1919, you did occupy the study in conjunction with Mr. Henry Lehrman?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And you do not recall whether you saw Mr. Norgaard there or not?

A: I do not remember.

Q: Do you recall of ever seeing Miss Rappe there?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Now, what time did Miss Rappe enter your room on the 5th of September?

A: About 12 o’clock, as near as I could judge.

Q: Twelve noon?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And there was no other lady in the room when she entered?

A: No, sir.

Q: And how long was she there before anyone else arrive?

A: I couldn’t tell you; Mrs. Delmont came up a few minutes afterwards, I think.

Q: You knew Miss Rappe before the 5th of September, did you not?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: How long had you known her?

A: Um-huh, about five or six years.

Q: About five or six years?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And when you say that—withdraw that. Did you know, before Miss Rappe came to your rooms on the 5th of September, did you know that she was coming there?

A: No, sir.

Q: Nobody told you that she was coming there?

A: No, sir.

Q: Mr. Fischbach didn’t say anything to you about her coming there, did he?

A: He said that he was going to phone her.

Q: Do you know whether or not he did phone her?

A: I presume he did.

Q: Do you know whether or not he did phone her?

A: I didn’t hear him phone.

Q: Did he tell you that he had phoned?

A: He said. “I am going to phone her.” He didn’t really say that to me. He said it to Mr. Fortlouis.

Q: He said that to Mr. Fortlouis in your presence?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Did he say in your presence whether she was coming up or not?

A: I don’t remember.

Q: Do you recall whether or not he received any phone calls from the time he phoned Miss Rappe until Miss Rappe came up into your room?

A: I do not recall that.

Q: Then I take it that the first you knew that Miss Rappe was coming up to rooms 1219, 1220 ,and 1221 was when she knocked on the door and came into the room?

A: I just heard Mr. Fischbach say that he was going to phone, and then a short time afterwards she came in.

Q: But from the time that Mr. Fischbach said that he was going to phone nobody had told you that she was coming up to the room and you did not know it until she came into your room?

A: No, sir.

Q: Where were you when she entered the room?

A: I was in 1219.

Q: You were not in room 1220 when she entered?

A: No, sir. but I saw her come in.

Q: How long afterwards did you enter room 1220?

A: Almost immediately.

Q: Almost immediately?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And how long did you remain in room after she arrived?

A: I remained there until I went into room 1219.

Q: And how long was that?

A: Well, from the time that she came in until around 3 o’clock.

Q: You remained there about three hours then?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And you were donned how when Miss Rappe entered room 1220?

A: I was clothed in this bathrobe and pajamas and slippers.

Q: What kind of pajamas were they, silk?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And slippers?

A: Yes, sir, and I had my socks on.

Q: You had your socks on?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And room 1219 was your room, wasn’t it?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Now, how long after Miss Rappe had entered room 1219, how long after that was it that Mrs. Delmont appeared?

A: Mrs. Delmont came in just a few minutes after Miss Rappe came in.

Q: And did you know how Mrs. Delmont happened to come to room 1220?

A: No, I do not know.

Q: You do not know?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did you know Mrs. Delmont before the 5th of September?

A: No, sir.

Q: And the first that you knew that Mrs. Delmont was coming to your rooms was when she knocked on the door and entered?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Nobody ever told you that Mrs. Delmont was corning up to your rooms?

A: No, sir.

Q: You didn’t hear anyone phone downstairs for her?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did you see or hear any one use a telephone in either of these three rooms at the time that Miss Rappe entered room 1220 until Mrs. Delmont entered?

A: Yes, sir, I saw Miss Rappe use the phone.

Q: Which phone did she use?

A: She used the phone in room 1220.

Q: In the same room that you were in?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: You didn’t hear what she said?

A: No, I didn’t hear what she said; I knew to whom she was talking.

Q: In that conversation did she mention the name of Mrs. Delmont?

A: No, sir; not that I recall; she talked to a lady by the name of Mrs. Spreckels.[8]

Q: Did you hear Miss Rappe mention the name of Mrs. Delmont from the time that Miss Rappe entered your room until the time that Mrs. Delmont appeared?

A: No, sir, she. never mentioned the name. She said she had a friend downstairs.

Q: Did she say who that friend was that she had downstairs?

A: No, sir.

Q: She never said that Mrs. Delmont was coming up to the room; never said that Mrs. Delmont was waiting downstairs or never said anything about Mrs. Delmont until she arrived, actually arrived in room 1220?

A: She never mentioned the name.

Q: She didn’t say that she was coming?

A: Not by name.

Q: You don’t recall that?

A: No, sir.

Q: You were in room 1220 when Mrs. Delmont arrived?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: What room did she enter?

A: She came into room 1220.

Q: Came into room 1220?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And you were still clothed as you have testified to?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Did you ever change those clothes from the time Miss Rappe arrived until Miss Rappe went into the bath of room 1219 as you have testified to?

A: No, sir.

Q: Now, who was present when Mrs. Delmont arrived in the room?

A: Miss Rappe, Mr. Sherman, Mr. Fortlouis and myself, and Mr. Fischbach, I think. He was in and out; I do not know whether he was there or not at that time.

Q: And how long after Mrs. Delmont arrived was it before someone else joined the party, if anyone, did join the party?

A: Well, I do not know; they kept coming in all the time.

Q: Well, who was the next person to enter your rooms after Mrs. Delmont arrived?

A: Miss Blake.

Q: Now, had you known Miss Blake prior to her coming to room 1220 on the day in question?

A: Never saw her in my life.

Q: Never saw her in your life before?

A: No, sir.

Q: And how long after Miss Rappe had entered that room was it that Miss Blake arrived?

A: I do not know; they all came in there, and they were all there by 2 o’clock, when Miss Blake left again to go to Tait’s. They all kept stringin’ in.

Q: Now, prior to the time that Miss Blake came into your room, did you know that she was coming?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did you know that any other woman was coming to your room on that day?

A: No, sir.

Q: Then the first you knew that any other woman was going to join the party was when Miss Blake knocked on the door of room 1220 and entered the room?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Nobody informed you that Miss Blake was coming up to your room on that date?

A: No, sir; never heard about it.

Q: You never heard about it?

A: No, sir.

Q: And you were in room 1220 when Miss Blake entered, were you not?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Now, how long after Miss Blake entered these rooms was it before Miss Prevost entered?

A: I couldn’t tell you in minutes.

Q: Well, about how long, approximately?

A: I do not know; she came in after Miss Blake did. I will guess the time if you wish me to. Probably twenty or twenty-five minutes—I don’t know.

Q: You don’t know?

A: No, sir

Q: Had you known Miss Prevost before she entered your rooms on the 5th day of September?

A: No, sir; not that I can remember.

Q: Nobody, prior to the time that Miss Prevost entered your rooms on the 5th day of September, had told you that she was coming up to your rooms?

A: No, sir.

Q: Prior to the time that Miss Prevost did come up on the 5th day of September, you did not know whether or not she was coming up to your rooms?

A: No, sir.

Q: Nobody told you that Miss Prevost or any other lady was coming?

A: No, sir.

Q: And after the entry of Miss Blake and the time that Miss Prevost arrived in your rooms on September 5, you had no idea that anybody else, or any other woman was coming to your rooms on that day?

A: Absolutely not.

Q: Then, sir, I take it from your testimony that you didn’t know at any time until these various parties knocked upon the door of your rooms, whether Miss Rappe, Mrs. Delmont, Miss Blake, or Miss Prevost was coming to your room. Is that correct?

A: No, sir, I did not.

Q: And all this time, while each of the ladies was arriving, you were still clothed, as you have testified, in your bathrobe and pajamas and slippers. Is that correct?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Now, what were you doing when Miss Prevost entered room 1220?

A: I was sitting in a chair,

Q: Well, what were you doing?

A: Talking to Miss Rappe and the rest of the people.

Q: What else were you doing?

A: Having some breakfast. I think, or lunch.

Q: Well, was it breakfast or lunch?

A: Well, it was lunch for some and breakfast for the others.

Q: Well, so far as you personally were concerned, what was it?

A: Breakfast.

Q: It was your breakfast?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: What time had you arisen that morning?

A: Between 10 and 11 o’clock, I guess.

Q: You had arisen between 10 and 11?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And you were then having breakfast?

A: Yes, sir, I had a cup of coffee.

Q: What did you have to drink with your breakfast?

A: I had coffee.

Q: Was there anything else to drink there?

A: On another table, yes, sir.

Q: And what was there upon that other table?

A: Scotch whisky, gin and orange juice?

Q: What else?

A: White Rock.

Q: And what else?

A: That is all.

Q: And how much whisky was there?

A: A bottle or two.

Q: And how much gin?

A: A bottle.

Q: And how much orange juice?

A: Two quart bottles.

Q: And how long had that been there?

A: They had been brought up.

Q: Well, how long before?

A: Well, sometime between the time that Miss Rappe came in and the time that Miss Prevost came in.

Q: They were not in the room prior to that time?

A: The whisky and gin was in the closet in room 1221. The water and orange juice was brought up by a waiter.

Q: Oh, the whisky and gin was there in a closet?

A: Yes, sir. |

Q: And who brought the whisky and gin out of the closet into room 1220?

A: Mr. Fischbach; he had the key.

Q: Now, what was said at that time?

A: Nothing said; he just set it down

Q: Well, did anybody suggest that the drink be served?

A: They kind of helped themselves is all.

Q: Who said that?

A: He said probably “help yourselves.“

Q: Yes, who said that?

A: Mr. Fischbach, I suppose. He brought it in.

Q: Did you say anything else about a drink before this time when this whisky and gin was brought in?

A: Did I say anything about it?

Q: Yes.

A: I don’t remember.

Q: And who was the first person to mention a drink?

A: I do not know that anybody mentioned it; he just brought it in.

Q: And Mr. Fischbach brought it in?

A: Fischbach brought it in; I do not remember just what time be brought it in, but I know that he brought it in. I know it was there all morning.

Q: Was it there before Miss Rappe arrived?

A: No, sir. I do not think so. I think he brought it in about that time.

Q: All right: what I wanted to know is when he brought it in, was there anything said about a drink by anybody there, by Miss Rappe, Miss Pryvon [sic],[9] Miss Blake, Mr. Sherman or Mr. Fortlouis?

A: No, sir, he just brought it in, that is all.

Q: He brought it in without saying a word?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: What did you say, or what did he say?

A: He set it down—probably, “There it is; help yourselves.”

Q: Well, tell us the words?

A: His exact words I do not know.

Q: Did you hear him say anything?

A: I cannot recall.

Q: Did you hear anybody say anything?

A: About this liquor being brought in?

Q: Yes.

A: Not that I ran remember particularly.

Q: Now, when did Mr. Semnacher come up to your room?

A: He came up after Mrs. Delmont.

Q: Well, how long after Mrs. Delmont arrived?

A: I couldn’t say exactly.

Q: Had you known Mr. Semnacher before his coming up to your room on the 5th of September?

A: I had known Mr. Semnacher several years.[10]

Q: You had known Mr. Semnacher for several years?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Did you know he was coming up to your rooms on this day?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did you know at any time, even for a minute before he entered your rooms on that day, that, he was coming up to your rooms on that day.

A: No, sir.

Q: Nobody mentioned the fact that he was coming up?

A: Not that I remember of.

Q: Now, from the time that Miss Pryvon entered room 1220, and you saw Miss Rappe go into room 1221, as you have testified to, what was being done in these rooms?

A: Well, people were eating, drinking, the Victrola was brought up and that is about all; just a general conversation.

Q: Well, who suggested that the Victrola—who, if any one, suggested that the Victrola be brought up?

A: Miss Rappe.

Q: Miss Rappe suggested that?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And whom did she suggest that to?

A: To me.

Q: And what did you say?

A: She suggested that we get a piano and I said. “Who can play it?” Nobody. Then I said “Get a Victrola.”

A: And who, if anyone, sent for a Victrola?

A: I telephoned for it.

Q: You phoned for it?

A: Yes, sir.

A: And you say the parties had been drinking up to this time. Had you indulged in anything?

A: I was eating my breakfast.

Q: You didn’t drink anything?

A: Yes, sir; after breakfast.

Q: And what were you drinking, gin or whisky?

A: I was drinking highballs.

Q: And after the phonograph was brought into the room, or the Victrola, what was done then by the people in room 1220?

A: Well, they danced.

Q: Did you dance?

A: Um, um.

Q: And how long did this dancing and drinking keep up?

A: All afternoon until I left, and some after that, I guess.

Q: All afternoon long?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: What time did you leave the room?

A: I went downstairs about 8 o’clock in the evening.

Q: Eight o’clock at night?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Where did you go to?

A: Down in the ballroom.

Q: Down in the ballroom of the hotel?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And were they still dancing when you came back to your room?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And what time did you return to your room?

A: Around 12 o’clock, I guess.

Q: And from the time you left your room until you came back you were down in the ballroom of the St. Francis; is that correct?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Now, you did know that one young lady was coming to your room that day, did you not?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And that young lady was coming at your invitation?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And what time was she to be there?

A: No special time; she just said that she would come there.

Q: No special time?

A: No, we were just going riding.

Q: Yes.

A: You had made this appointment the preceding day?

A: The preceding evening.

Q: The preceding evening, that would be the night of the 4th?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And no particular time was set, she was just coming over, and you were going riding?

A: Yes, sir, she said that she would call up or come over.

Q: What time did Mr. Fischbach, leave your rooms, do you know?

A: He left sometime between 1:30 and a quarter to 2?

Q: He left between 1:30 and a quarter to 2?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And had you had any conversation with him prior to his leaving?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: You knew he was leaving, did you not?

A: Yes, sir, he borrowed my car.

Q: Oh, he borrowed your car?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And did he tell you where he was going in your car?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And what did you say?

A: I said, “All right, go ahead.”

Q: Yes. When did you next see Mr. Fischbach?

A: When he came into room 1219.

Q: Well, how long after he had left your room was that?

A: Probably an hour and a half, and maybe a little less, or maybe a little more, I couldn’t say.

Q: What time did ho leave your room, did you say?

A: Between half past one and a quarter to two.

Q: Did Mr. Fischbach tell you where he was going when he left your rooms and you loaned him your car?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And did he tell you who he was going with?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did he tell you he was going to call on anyone?

A: No; he just told me he was going out to the beach with some friend of his; was going to take him out there to look at some seals; he thought—this fellow thought maybe he could use them in a picture.

Q: Now, after this Victrola was brought up, did Miss Rappe dance?

A: No, sir; I didn’t see her dance.

Q: You didn’t see her dance. And what did she say when she suggested that a piano be brought up? Just give the conversation at that time?

A: She says, “Can’t we get music or a piano, or something?’” I says, “Who can play it?”

Q: Did she say what she wanted the piano for?

A: Just said she wanted some music.

Q: When it was decided nobody could play it, who suggested the Victrola?

A: I did.

Q: And what did you say? Just give the conversation about the Victrola.

A: The conversation?

Q: Yes, the conversation.

A: I don’t know the conversation. I says, “I will get a Victrola—I will see if I can get a Victrola.”

Q: Did you say what you were going to get a Victrola for?

A: What I was going to get a Victrola for? We wanted music—she wanted music.

Q: Up to the time that the Victrola was brought into the room was anything said about dancing?

A: No, sir.

Q: Miss Rappe never mentioned dancing?

A: No, sir; not to me.

Q: Miss Rappe did not say to you, “Let us have some music so we can dance”?

A: Not to me.

Q: Did you hear her say it to anyone else?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did you hear anyone say it?

A: No, sir.

Q: You say that you danced after the music was brought?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Did you dance with Miss Rappe?

A: No, sir.

Q: Who did you dance with?

A: Miss Blake.

Q: Did Mr. Sherman dance?

A: I can’t recall whether he did or not.

Q: Did Mr. Fischbach dance?

A: Mr. Fischbach was not there at that time.

Q: Who else was there? What other men were there?

A: Mr. Sherman, Mr. Fortlouis, and Mr. Semnacher—I can’t keep track of him, he was in and out, all day.

Q: Did Mr. Semnacher dance at any time?

A: No.[11]

Q: Did you see Mr. Fortlouis dance?

A: No, I didn’t see Mr. Fortlouis.

Q: Did Mr. Sherman dance?

A: Yes, he danced once in a while.

Q: Whom did he dance with?

A: I suppose with Miss Pryvon or Miss Blake.

Q: Do you know—did you see him dancing with anybody?

A: At that time I don’t recollect whether he did or not; I know later on he did.

Q: Whom did he dance with later on?

A: There was a couple of girls came up later on, about 4 o’clock.

Q: That was about 4. Then you never saw Miss Rappe dance at any time in your room?

A: Not that I can remember. I did not dance with her.

Q: You did not dance with her?

A: No, sir.

Q: And yet she was the one that asked for the music?

A: She asked for the music, yes, sir.

Q: You have seen Miss Rappe on other occasions, have you not, when there has been music?

A: I have never been with her only once.

Q: You have seen her on other occasions?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Where there has been music?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Have you ever seen her dance?

A: Certainly I have seen her dance.

Q: Now, did you, at any time up to 3 o’clock in the afternoon of the 5th of September, tell anyone in your rooms that they would have to leave your rooms?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Yes. Whom did you tell they would have to leave?

A: I did not tell that party they would have to leave; I asked Mr. Sherman to ask them.

Q: You asked Mr. Sherman to ask whom?

A: Mr. Fortlouis.

Q: Is that the only person you asked to leave your rooms?

A: Yes, sir, in the afternoon.

Q: Well, at any time, I am speaking now of any time from 12 to 3 o’clock, did you tell anybody in your rooms outside of this Mr. Fortlouis that you have mentioned, that they would have to leave your rooms in the St. Francis Hotel?

A: I did not say they would have to leave; I was stalling to get him out. I said there was some press—some newspaper people coming up, to get him out.

Q: I am saying, with the exception of Mr. Fortlouis, did you suggest to any one that they would have to leave your rooms?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did you ask anyone to leave your rooms?

A: No, sir.

Q: What time did Mrs. Taube—is that the name, Mrs. Taube?

A: Mrs. Taube.

Q: Yes, what time did she enter your rooms?

A: The first time?

Q: On the 5th of September?

A: The first time she entered the room was, I guess, between, somewhere around 1:30. I guess, probably a little before.

Q: And she entered your rooms ai 1:30. How long did she remain there?

A: Five or ten minutes.

Q: Five or ten minutes. And she left?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Was there any conversation between you and Mrs. Taube as to her returning?

A: She said she would call later. I told her that we would go riding I says, “I loaned Mr. Fischbach my car for a few moments; he is going to use my car and when he returns with it we will go out.”

Q: And what time did you tell her to return?

A: I didn’t tell her to return. She said she would call back.

Q: She said she would call back?

A: Later on in the afternoon.

Q: Was there anything else said about what you were going to do, between you and Mrs. Taube?

A: She asked me who all these people were, and I told her. “You can search me. I don’t know.” I tried to introduce her; I couldn’t remember their names. I introduced her to Miss Rappe, I think.

Q: She stayed there for how long?

A: Just a few moments.

Q: And then she left?

A: Yes.

Q: Do you know why?

A: Yes, I think I do.

Q: Why?

A: Well, she had another girl with her.

Q: Yes.

A: And she didn’t want to stay there.

Q: Did she say why she did not want to stay there?

McNab: I object to that as not proper cross-examination. It has nothing to do with the issues of this case.

Court: Objection overruled.

Arbuckle: This girl? Mrs. Taube says why—she didn’t say at that time. She said she was going down, that she would come back.

Friedman: What time did she return? Did she return?

A: Yes, she returned later on after this trouble in 1219; came up about ten minutes after Mr. Fischbach, somewhere along there.

Q: And how long did she remain at that time?

A: She remained in the rooms until after Miss Rappe had been taken to 1227 and I came back.

Q: Yes. And then she went out?

A: Then she went out again, yes, sir.

Q: You did not go with her?

A: No; she did not go riding.

Q: You did not go riding?

A: No.

Q: And you saw her again that day?

A: Yes, sir; she called back about 6 o’clock in the evening, I think.

Q: Now, do you know why Mrs. Taube went away after you had moved Miss Rappe to room 1227?

A: I don’t know; she just seemed to me like she was a little peeved or something.

Q: Isn’t it a fact that she said something to you that indicated that she was a little peeved at the time?

A: Yes, she did.

Q: What was it she said?

A: She asked me who those people were, and what they were doing; I told her I didn’t know who they were.

Q: And she asked you on the first occasion, didn’t she?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And that is why she left, wasn’t it, because these people were in your rooms?

A: I probably think so.

Q: And you did not go with her on either of the occasions in the afternoon?

A: No.

Q: Now, upon Mrs. Taube’s first visit to your room on the 5th of September, about half past one, as you have testified to, what was Miss Rappe doing at that time?

A: She was sitting on a settee in the corner, I think.

Q: Did she remain there all the time that Mrs. Taube was in the room on the first visit?

A: I can’t remember whether she did or not: I talked to Mrs. Taube.

Q: You can’t remember whether she did or not. Did you notice where Miss Rappe was after Mrs. Taube left on her first visit? I was talking to Mrs. Taube. I don’t know.

Q: You saw Miss Rappe go into room 1221. did you?

A: Yes, sir, later on.

Q: You introduced Mrs. Taube to Miss Rappe I believe you said?

A: I think I did; I don’t know; maybe somebody else; I just can’t recall whether I introduced her.

Q: Well, now, did you or didn’t you?

A: I don’t know whether I did or not.

Q: Did anyone else in that room know Mrs. Taube that you know of?

A: Yes, Mr. Fischbach knew her, but he was not there.

Q: He was not there, so you don’t know whether you introduced her to Miss Rappe, or not?

A: No, I don’t know.

Q: Do you know whether or not she was introduced to Miss Rappe?

A: Yes, sir, I think she was. I suppose so.

Q: Well, were you present when she was introduced to Miss Rappe?

A: Well. I don’t know; I have a habit of introducing people. I don’t always do it.

Q: We are not talking about your habits; we are talking about what happened in this room at this time, about 1:30 on September 5.

A: Yes, I think she was introduced, as near as I can remember.

Q: All right; now where was Miss Rappe when you were introduced to Mrs. Taube? What was she doing? Was she standing up or sitting down?

A: I think she was sitting on the settee, as near as I can remember.

Q: All right; how was she dressed?

A: Miss Rappe or Mrs. Taube?

Q: Miss Rappe?

A: She had on a green dress, a green skirt and a green jacket.

Q: Did she have a hat on?

A: I can’t remember whether she had a hat on at that time or not.

Q: Well, you don’t know whether she had a hat on or not; is that the answer?

A: Yes.

Q: Was her hair up or down?

A: I can’t remember that, either.

Q: You can’t remember that. You don’t recall seeing her hair down at that time, do you?

A: No, I do not.

Q: Now, when Miss Rappe went into room 1221, as you have testified to, was she still dressed as she was introduced to Mrs. Taube?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Did she have a hat on at that time, or not?

A: I don’t—no, she did not have a hat on then.

Q: Was her hair up or down at that time?

A: I can’t remember exactly.

Q: You can’t remember; you don’t remember of seeing her hair down at that time, do you?

A: No, sir.

Q: How long did she remain in 1221?

A: I don’t know.[12]

Q: You don’t know? You saw her go in?

A: I saw her go in, yes, sir.

Q: You saw her go in room 1219?

A: I did not.

Q: You did not—did not see her go into room 1219?

A: No, sir.

Q: How long a time elapsed from the time you saw Miss Rappe go into room 1221 until you went into room 1219?

A: I couldn’t tell you.

Q: Well, what were you doing when she went into room 1221?

A: I was sitting there talking to her when she went into 1221.

Q: You were sitting there talking to her?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And she got up and went into room 1221?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: What did you do when she got up and went into room 1221?

A: I got up; I don’t know what I did; went to the Victrola or something, or danced; I don’t know; I don’t remember at that time.

Q: Well, how long a time would you say elapsed from the time you saw Miss Rappe go into room 1221 until you went into room 1219?

A: I couldn’t tell you.

Q: Well, was it a half hour?

A: No, I don’t think it was that long.

Q: Well, fifteen minutes?

A: I wouldn’t say what time it was. It was—

[Order inferred[13]]

Q: Now, you can’t fix the time—I withdraw that. What time did Miss Rappe to into room 1221?

A: I couldn’t tell you just what time.

Q: Well, you say that you had been sitting in 1220 talking to her when she went in there?

A: Yes.

Q: Where were you sitting?

A: She was sitting here, and I was sitting on this chair here (indicating on diagram).

Q: What time did Fischbach leave your room?

A: Between 1:30 and a quarter to 2, I guess.

Q: Between 1:30 and a quarter to 2. Did Miss Rappe go into room 1219 before or after Fischbach left your room?

A: It was after Miss Blake had come back from Tait’s, sometime between 2:30 and 3 o’clock.

Q: Sometime between 2:30 and 3 o’clock. And what time was it—withdraw that. You say that you told somebody to tell Mr. Fortlouis that the reporters were coming up to your room?

A: Uh huh (affirmative).

Q: Who did you tell?

A: I told Mr. Sherman, I believe.

Q: And when did you tell him that?

A: Oh, I can’t just remember when.

Q: You can’t remember when it was. Did Mr. Fortlouis leave your room?

A: Yes, but I don’t know when he left.

Q: You don’t know when he left. Well, how long after you told Mr. Sherman to tell him that the reporters were coming upstairs did he leave? Did he leave alone?

A: I can’t remember; I don’t know when he left.

Q: You don’t know when he left. Did he leave before or after Miss Rappe went into room 1221?

A: I don’t know.

Q: Did you see Mr. Semnacher again after he went out with Miss Blake?

A: He was in and out all afternoon. I can’t—I couldn’t tell you anything about him at all.

Q: Now you say that Miss Blake came in in about a half an hour or so; is that what you said?

A: Yes.

Q: How do you fix that?

A: That is just a judge of time; I don’t know; I couldn’t tell you; it seemed to me.

Q: When did you next see her after she went to rehearsal?

A: When she came back to the room.

Q: What was she doing? What was the occasion? What attracted your attention to her? Did you see her come in?

A: Not that I remember; she just appeared in the room.

Q: All of a sudden you discovered she was there?

A: She was back.

Q: Right in the middle of the crowd again?

A: Yes, she was there.

Q: Now, after you had discovered that Miss Blake had returned and Miss Rappe was in the room, what did you do? Play some more music?

A: Yes; the music was going.

Q: Did you dance after that?

A: I think I danced with Miss Blake, yes; I am not sure.

Q: Do you remember if, after you discovered Miss Blake had returned to this room, of changing any of the phonograph records yourself?

A: Yes, I think I did; I changed—

Q: How many?

A: Whoever was closest to it; I don’t know.

Q: You don’t remember what you did. As a matter of fact, you don’t remember how long it was after Miss Rappe went into room 1221 that you went into 1219?

A: Well, I couldn’t tell you exactly; no.

Q: But your recollection is it was five or ten minutes?

A: I believe, I don’t know; it might have been more or less.

Q: It might have been less?

A: I don’t know.

Q: It might have been as little as two or three minutes, isn’t that a fact?

A: No.

Q: Well, it might have been that short a period of time?

A: I couldn’t tell you, because that is the last time I saw her, when she went into 1221.

[Order inferred]

Q: As a matter of fact, was it only a minute or two?

A: I don’t know.

Q: Do you recall doing anything from the time that Miss Rappe went into room 1221 until you went into room 1219?

A: Yes, certainly.

Q: What did you do?

A: I put—changed a record on the phonograph; I think I danced with Miss Blake; I am not sure what I did.

Q: Then you don’t recall what you did; you don’t recall doing anything?

A: I was around the room; I don’t just exactly know what I was doing.

[Order inferred]

Q: You don’t know what you were doing or how long a time elapsed—is that it?

A: I couldn’t tell you.

Q: And what time was it that you entered the room 1219?

A: About 3 o’clock.

Q: About 3 o’clock? And how was it that knew it was 3 o’clock?

A: I looked at the clock.

Q: You looked at what clock?

A: On the mantel.

[Order inferred]

Q: Isn’t it a fact that the clock was not running when you looked at it?

A: (laughs) No, sir; that is not so.

Q: Are you certain the clock was correct?

A: Well, everything else in the hotel is pretty good, so I supposed the clock was all right.

[Order inferred]

Q: What time was Mrs. Taube coming back?

A: She said she would call back; she didn’t say any particular time.

Q: Then you didn’t know whether she was coming back about 3 o’clock or not, did you?

A: She said she was.

Q: Oh, what time did she say she was coming back?

A: I told her when she came up. I says, “Mr. Fischbach has got my car; is going to use my car; when he comes back we will go riding.” And she says, “Where is he going?” I says, “He is going to the beach and back.” She says, “I will come back after a while.”

[Order inferred]

Q: And, as a matter of fact, when you arose on the 5th of September and went into the bathroom to clean up, it was your intention then to get ready and go out riding with Mrs. Taube?

A: When she came in.

Q: When she came in?

A: There was no particular time set; it was just for the afternoon.

Q: But you did not get dressed at that time?

A: No, these people kept coming in, and I was trying to be sociable.

Q: With whom?

A: With them.

Q: They were not your guests?

A: No, I didn’t want to insult them.

Q: You didn’t invite them there, did you?

A: No, sir.

Q: With the exception of Miss Rappe, you didn’t know anybody that was coming there at that time, any of these young ladies?

A: No.

Q: You did not invite them?

A: No.

Q: And you didn’t tell anyone else to invite them?

A: No.

Q: And they were not your guests?

A: No.

Q: And you had an appointment to take Mrs. Taube out riding?

A: Yes.

Q: And still you figured you couldn’t go away without insulting those people, is that right?

A: No, I figured I couldn’t go away until Mr. Fischbach came back with my car.

[Order inferred]

Q: And you don’t know what you did after that; and you don’t know how long a time elapsed after that before you went into room 1219?

A: No, I suppose I did what I had been doing; there was music and dancing and kidding around the room.

Q: You’ve heard the other witnesses testify on the stand to that time, haven’t you?

A: I’m not telling their testimony.

Q: Well, refresh your memory and don’t argue about it. You say it was 3 o’clock when you went into room 1219 and that this was a little after you noticed Miss Rappe go into room 1221—when did you see Miss Rappe come out of room 1221 and go into 1219?

A: I didn’t see her leave room 1221.

Q: How long after you saw Miss Rappe go into 1221 did you go into 1219?

A: I don’t remember; it may have been five or ten minutes. I’ll guess for you if you wish, but I couldn’t say exactly.

[Order inferred]

Q: And you had an appointment to take Mrs. Taube out riding?

A: Yes.

Q: And still you figured you couldn’t go away without insulting those people, is that right?

A: No, I figured I couldn’t go away until Mr. Fischbach came back with my car.

Q: Now, isn’t it a fact, Mr. Arbuckle, that Mrs. Taube came into room 1220 in the St. Francis Hotel on the 5th day of September, between the hours of 1 and 2 o’clock in the afternoon thereof, before Mr. Fischbach had left your rooms and used your car?

A: No, sir, I don’t think so.

Q: You are positive of that, are you?

A: No, I would not be positive.

Q: You wouldn’t be positive. Then are you positive that you told Mrs. Taube that Mr. Fischbach was out using your care when she arrived at your rooms?

A: I don’t know whether I told her he was, or he was going to use it. I know I gave him my word he could have my car. I told her words to that effect.

Q: You don’t know whether you told her that he did have or he was going to have your car?

A: I gave her to understand that he was going to use the car for a while.

Q: Had you and Mrs. Taube decided on any particular place to go driving on this 5th of September?

A: No particular place.

Q: No particular place at all?

A: No.

Q: And all that Mr. Fischbach wanted your car for was to go out and look at seal rocks?

A: Not seal rocks; he was going out to look at some seals that he was going to use in a picture.

Q: Some seals. Those seals were where, did he tell you?

A: By the beach.

Q: And you don’t know how long a time elapsed from the time that Miss Rappe went into room 1221 until you went into 1219?

McNab: If the court please, we are supposed to end this trial sometime. I object to the same questions being asked more than ten times.

Court: Proceed with the examination.

Friedman: Very well, answer the question.

Arbuckle: What was it? (Question read by the reporter.)

Schmulowitz: I object to the question on the ground it has been asked and answered several times, if the court please.

Court: Objection overruled.

Arbuckle: No, I couldn’t tell you.

Friedman: Can you recall of speaking to anyone at all from the time that Miss Rappe went into room 1221 until you went into room 1219?

A: Me speaking to anyone? Can I recall me speaking? If there was people in there, I suppose I spoke to them.

Q: Can you recall of speaking to anyone, not what you suppose you did? Have you any recollection, any memory upon it all?

A: If there were people in the room, I would speak to them.

Friedman [to Louderback]: We ask that the answer be stricken out as not responsive, and ask that the witness be directed to answer the question.

Court: It goes out.

Arbuckle: I spoke to people.

Friedman: Who did you speak to?

A: Miss Blake.

Q: You spoke to Miss Blake?

A: Yes.

Q: Who else, if anyone?

A: I don’t know. I suppose Miss Pyvvon [sic], or whoever was in there at the time; I don’t know.

Q: Who do you remember speaking to, not what you suppose?

A: Well, I spoke to whoever was in the room.

Q: Whoever was in the room; and if there were five people in the room, you spoke to the whole five of them?

A: I don’t think there were five people.

Q: If there were three people in the room, you spoke to the three of them; is that correct?

A: I might have spoken to them, yes.

Q: Who was in the room when Miss Rappe went into room 1221?

A: Miss Blake, I think Miss Pyvvon was, possibly Mr. Sherman. I don’t recollect.

Q: And you recall speaking to Miss Blake during that period of time?

A: Yes.[14]

[Order inferred]

Q: Do you recall speaking to Mr. Sherman during that period of time?[15]

A: I say I don’t recollect whether he was there; possible he was there; possibly he was not.

Q: Then you have no recollection of whether you spoke to him?

A: No.

Q: Do you recall what you said to Miss Rappe at that time?

A: No.

Q: Now, prior to your going into room 1219 and locking the door, as you have testified to—

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Did you tell anyone who was in either one of these three rooms what you were going into room 1219 for?

A: No.

Q: You didn’t tell anyone you were going to get dressed?

A: No.

Q: Just walked in and locked the door?

A: Walked in.

Q: And locked the door?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: When you spoke to Miss Blake just before going into room 1219, you didn’t tell her what you were going into 1219 for?

A: No, sir.

Q: Never said a word to her about it?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did you tell anyone that you were going to leave?

A: No, sir.

Q: And at 3 o’clock you decided, just without speaking to anyone about it, that you would go in and get dressed so that would be ready to go riding; is that it?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: What did you do after you entered room 1219? What was the first thing you did?

A: Locked the door.

Q: You locked the door; and which door?

A: The door leading into 1219.

Q: There are two doors; was it the door from 1219 into 1220?

A: The door opening into 1219. As near as I can recollect, it had a mirror in it.

Q: You don’t recall closing more than one door do you?

A: No, I just closed the door and locked it.

[Before the noon recess, Jane Walsh briefly took the stand to officially identify the preserved bladder of Virginia Rappe as evidence.]

Friedman: Now, after Miss Rappe had gone into room 1221, did you remain in room 1220?[16]

Arbuckle: Yes, I was in 1220.

Q: And you remained in there until you went into room 1219 as you have testified to; is that correct?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Did you at any time see Miss Rappe come out of room 1221?

A: No, I didn’t see her after she went into room 1221.

Q: You are positive you didn’t see her come out of room 1221?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Now, from the time that Miss Rappe went into room 1221, until you went into room 1219, will you just show on this diagram which portion of room 1220 you remained in?

A: I do now know what part of the room I remained in; I was in the room.

Q: And you do not know what portion of the room you remained in?

A: No.

Q: And you are positive you didn’t see Miss Rappe come out of room 1221?

A: Absolutely.

Q: And you remained in room 1220 all that time?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And you remained in room 1220 all that time?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And you can’t recall what you did while you were in there?

A: I did the same thing as I had been doing all the afternoon.

Q: But more specifically than that you cannot say?

A: No.

Q: And what was the first thing that you did after you went into room 1219?

A: I closed the door and locked it.

Q: And that was the door that opened in as far as room 1219 was concerned?

A: I think so; I am not positive.

Q: And why did you lock the door?

A: I was going to get dressed.

Q: Is that why you locked the door?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Is it your habit to lock that door when you to in to get dressed?

A: Yes, if there is anybody in the room—the ladies were there.

Q: Are you positive that is the only reason you had in locking the door?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: From 1219 to 1220?

A: Yes, sir, to change my clothes and get dressed.

Q: Did you bathe that morning?

A: Yes.

Q: Did you see Josephine Keza, the chambermaid, while you were bathing?

A: I did.

Q: Where were you at the time?

A: I was in the bathroom, shaving. She opened the door, and then excused herself and went out.

Q: Did you have your bathrobe on?

A: No.

Q: What did you have on?

A: Nothing.

Q: Nothing?

A: Nothing.

Q: And you locked the door so you would not be disturbed while you were dressing?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: So you did not lock the door at all from room 1219 into the corridor?

A: No, I did not; I never gave it a thought.

Q: Why didn’t you lock the door from room 1219 out into the corridor?

A: I told you I never gave it a thought.

Q: All you did think about was the door between 1219 and 1220 being open, being unlocked?

A: What do you mean? I locked it because there were so many coming back and forth through the rooms.

Q: Well, had anybody gone out into the hall?

A: I don’t know.

Q: Do you remember Miss Rappe going in there at any time?

A: No, sir, but the doors were open.

Q: Now, after you had locked the door to keep those ladies out of room 1219, while you were dressing, what did you do?

A: I went straight to the bathroom.

Q: You went straight to the bathroom?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: What did you do then?

A: Opened the door.

Q: You opened the door?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And did the door open readily?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And then what occurred?

A: The door struck Miss Rappe where she was lying on the floor.

Q: You say the door struck Miss Rappe where she was lying on the floor?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And what was she doing at that time?

A: Just holding her stomach with her hands and moaning.

Q: Had she been ill up to that time?

A: No, sir.

Q: Then what did you do?

A: Then I asked her if there was anything I could do for her

Q: She wanted to lie down?

A: Yes.

Q: Then what did you do?

A: I helped her into the bedroom.

Q: From the time that you picked her up off the floor—I withdraw that. From the time that you [. . .] until you helped her into 1219 [. . .]

A: No.

Q: She held the water that you gave her on her stomach until you got her into room 1219?

A: I suppose so.

Q: How did you assist her from the bathroom to the bed?

A: She walked

Q: She walked. Did you help her in any manner?

A: I put my arm around her.

Q: You put your arm around her and assisted her, and you walked off to which bed?

A: To the little bed.

Q: Then what did you do?

A: She sat down on the edge of the bed.

Q: She sat down on the edge of the bed?

A: Yes; then laid over on it.

Q: Then laid over on the bed. Which way was she facing?

A: She was facing (going to diagram)—facing this way (indicating). She sat down here and just laid over on the bed with head toward the foot.

Q: With her head toward the foot?

A: Yes, sir. I picked her feet up and put them up on the bed.

Q: Then what did you do?

A: I went back into the bathroom.

Q: You went back into the bathroom. What did you do in the bathroom?

A: Well, I went back into the bathroom.

Q: All right. How long were you in the bathroom?

A: Three or four minutes, or a couple of minutes, I guess. I don’t know.

Q: Then what did you do?

A: I came out again.

Q: You came out again [. . .] I take it?

A: Naturally. [. . .]

Q: How, after you had—after Miss Rappe had been seated on this small bed, as you have testified to, and after she lay over with her head toward the foot, and you raised her feet up upon the bed, in which portion of the bed was she lying? Was she lying in the center of the bed, on one side or the other?

A: She just laid over in the bed; I didn’t notice whether she was to one side or the other.

Q: But it was on the side nearest to the window of the room that she sat down; is that correct?

A: Yes, sir?

Q: Now, then, what did you do after you came out of the bathroom?

A: I found her in between the beds.

Q: You found her in between the beds after you came out of the bathroom?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And you were only in the bathroom how long?

A: Three or four minutes, I guess.

Q: Three or four minutes; and you found her in between the beds. Which way was her head when you found her?

A: Facing out toward the foot of the beds

Q: Just show upon the diagram?

A: She was lying right in here (indicating on diagram).

Q: Right in there?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Which way was she facing?

A: Her head was this way.

Q: Her head was that way; which way was her face? Toward the window or toward the door, or was it facing toward the ceiling?

A: She was lying on her back.

Q: While you were in the bathroom, did you hear any noise in 1219?

A: No, I did not.

Q: You did not hear her fall out of the bed?

A: No, sir, I did not; I did not see her.

Q: Did she holler or was there any sound?

A: No, she was just moaning, holding her stomach and thrashing around on the floor.

Q: On the floor?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: What condition was she in when you went into the bathroom? You say you helped her up on the bed. Was she moaning then?

A: No, she just appeared to be sick and laid over on the bed.

Q: All right. After you went into the bathroom, and after you placed her on the bed, when was the first time you heard her moaning?

A: I heard her moaning when I came into the room, and she was lying between the beds.

Q: What did you do?

A: I put her on the big bed.

Q: Which way did you put her upon the big bed?

A: I picked her up and just put her on the big bed like this (illustrating), pulled up to a sitting position, and took hold of her, and put her on the bed, turned her around and laid her down on the bed.

Q: Did you turn around with her?

A: No, I just picked her up to a sitting posture. I couldn’t get to the side of her; there isn’t enough space, I just reached over like that, and picked her up and sat her over on the bed, and turned her around, and put her head upon the pillow.

Q: Then what did you do?

A: [. . .]

Q: Did you put her feet on the bed?

A: I put her whole body on the bed.

Q: [. . .]

A: I didn’t notice it particularly. I went right out of the room then to get Mrs. Delmont.

Q: Now, when you picked her up, when you started to lay her out upon the small bed, did she say anything at that time.

A: She might have said something.

Q: Now, did she—not what she might have said—did she say anything that you remember?

A: I can’t remember what she said exactly, or—

Q: Then she did say something to you, but you can’t remember it. Is that true?

A: She might have said something. I don’t know.

Q: Not what she might have said. Did she—do you remember her saying anything?

A: I can’t remember whether she did or not.

Q: You don’t know whether she did or at that time?

A: No.

Q: Did she, when you picked up, picked her feet up to straighten them out upon the bed, did she cry or moan at that time?

A: Not at that time, no.

Q: Never said a word. Did you place a pillow under her head?

A: No, I did not.

Q: You did not place a pillow under her head. There was a pillow on the bed, was there not?

A: Yes.

Q: And you did not place it under her head; you just laid her out and walked into the bathroom?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: When you came back, she was upon the floor between the beds?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: When you picked her up in this sitting position, what did she say then?

A: She didn’t say anything; she was just groaning and holding her stomach.

Q: She was just groaning and holding her stomach?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Was she groaning very loud?

A: Not particularly.

Q: Not particularly loud?

A: No, she just seemed to be in pain, short pains, or something.

Q: Was she groaning as loud as you are talking now?

A: I couldn’t tell you just how loud she was groaning; she just seemed to be—

Q: You couldn’t hear her groan when you were in the bathroom, could you?

A: No.

Q: Did she say anything when you raised her to this sitting position?

A: No.

Q: And did you say anything when you picked her up in this position that you have described to the jury?

A: No.

Q: Did she say anything when you seated her upon the bed and helped her down upon the bed?

A: No, she did not.

Q: Did she say anything when you straightened her out upon the bed?

A: No; I just turned her around to straighten her out but she kind of rolled over.

Q: She never said anything from the time you came out of the bathroom until you put her one the bed, so far as you know?

A: Not that I can remember.

Q: Now, did she wrench [retch?[17]] [. . .] while you were picking her up off the floor just before you placed her upon the bed?

A: She was just holding her stomach and groaning. [. . .]

Q: After you laid her upon the bed [. . .] as you have testified; what did you do then?

A: Went out of the room.

Q: You went out of the room?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Where did you go?

A: To 1220.

Q: To 1220. Did you unlock the door?

A: Yes.

Q: From the time you came into room 1219, from the time that you locked the door between room 1219 and room 1220, until you unlocked the door, as you have testified to, did you hear any sounds in room 1220?

A: No, I did not.

Q: Did you hear anybody at any time knock upon that door?

A: I did not hear them, no.

Q: Did you hear anybody at any time holler to you through the door?

A: No.