What has challenges anyone giving serious thought to the Arbuckle case—from lawyers and reporters in 1921 to this writer over a century later—is to reimagine the sequence of events that comprise Virginia Rappe’s crisis in room 1219 of the St. Francis Hotel as well as Roscoe Arbuckle’s culpability or innocence. The trial transcripts provide some answers if one is patient enough to read them. There you can see that District Attorney Matthew Brady and his assistants were confronted with how to arrange that sequence to advance their case against the comedian. His lawyers, to counter this, rearranged the sequence and provided an alternate to defend their client. That said, neither sequence is necessarily faithful to what happened seamlessly and without self-serving jump cuts of courtroom economies.

The most important of these discrete events concerned Virginia Rappe’s utterance: “I am dying, I am dying, he hurt me.” Prosecutors massaged these phrases from witness testimony so that a jury might conclude that Rappe had accused Arbuckle, an accusation fundamental to the charge of manslaughter. In response, the comedian’s lawyers found a convincing way to redirect Rappe’s accusation at Arbuckle’s roommate at the St. Francis Hotel, namely the comedy director Fred Fishback, whose role in organizing the 1921 Labor Day party, procuring women, and, despite not being a drinker, ensuring the supply of liquor, is very much discussed in my book. He is very much a person of interest.

Neither strategy on the part of the prosecution and the defense factored in that Rappe couldn’t have said those words so easily, so plainly, if at all. Nor was she very alert as her medical emergency progressed. Indeed, she went into shock and lost consciousness soon after Arbuckle left her fatally injured in his bedroom.

The ministrations of the first responders among the party guests were intended to learn what was wrong with Rappe. They found her writhing in the middle of a wet, disheveled bed. She was still fully clothed, still wearing her high heels. She clutched her lower abdomen. She was still verbal when she saw or sensed the presence of others in 1219. Then she kept complaining of her pain, saying over and over, “I am dying, I am dying.”

Being reassured that she was going to live gave Rappe little consolation. Her pain was excruciating enough to frighten her and anyone looking on. She became increasingly hysterical and started to tear at her clothes, which I attribute to going into shock while simultaneously exhibiting many of the symptoms associated with panic disorder.

Seeing this horrified Arbuckle and he immediately disassociated himself. He had two of his guests, both call girls, Zey Prevost and Alice Blake, try to dress Rappe and take her back to the Palace Hotel. But it was too late for that. So, Blake took it upon herself to pull Rappe up and off the wet bed after she had been undressed. Then, walking backward two or three steps, Blake let herself fall with her burden still on top of her. Unable to get out from under Rappe, whose body had gone slack, Fishback stepped up and lifted Rappe off of Blake. This was the first time Fishback handled Rappe.

At some point after Rappe’s “first” lift, Blake tried to get Rappe to drink bicarbonate of soda from a glass of hot tap water. But she could not swallow and the solution dribbled from her lips. Meanwhile, Prevost noticed that Rappe’s eyes were rolling backward.

From this point on, the prosecutors and defense lawyers were arbitrary in where to place events in a straight line. Blake, Prevost, Fishback, and other witnesses provided jigsaw pieces that almost fit but had to be forced together. Thus, a juror could see Arbuckle standing by an open window overlooking the light shaft outside room 1219. There he was within earshot when Rappe accused him, an important feature of being charged not only with manslaughter but with murder, too, if a woman is raped and dies as a result. And by that window, he responded to her. He told her to “shut up.” He threatened to throw her from the twelfth-floor to make her stop. Then he approached her with an ice cube, which he inserted into her vagina—ostensively to “come to” (pun and double entendre aside). A juror paying more attention, however, could see the problem. The victim was unconscious. So, how could Miss Rappe speak or pick someone out in the room to accuse him of hurting her?

The prosecutors never backed down from the paradox of the accusation—and never got over how it devolved from Prevost having heard “he killed me.” They could only go back to their signed statements, which had been extracted by compromise if not duress. As for Arbuckle’s lawyers, they could assert that Rappe meant someone else and Fishback served that purpose, given how much he had handled Rappe. They didn’t have to stretch the truth. Early on, Fishback admitted to the District Attorney’s men that he had tried to help Rappe. “They told me to pick her up by the feet,” he said in an unsigned statement made a few days after Rappe’s death. “One of the girls told me that, so the blood would rush down to her head. I got her up—held her up. She seemed to be a little relieved.”[1]

Not only did Fishback handle Rappe twice so far. He took responsibility for the following acrobatic feat, which is recreated in this scene from the working manuscript:

[. . . ] the only heavy lifting that Zey, Alice, and Maude agreed on followed the abortive attempt to make Virginia drink the bicarbonate of soda. Once more Alice tried to lift her up on her own and walk her toward 1219’s—this after someone, possibly Fishback himself, had suggested that a cold bath might better revive Virginia.

After enough water had been drawn, he grabbed Virginia’s arm and leg and carried her bodily sideways through the narrow bathroom door. Alice followed, cradling the head in the awkward task of dropping Virginia into the water.

Instead of regaining consciousness, Virginia began to scream in pain again and writhe about, sloshing cold water over the sides. So, Fishback pulled Virginia out. Alice toweled her off on the toilet seat. Then they carried her back to the dry bed.

Seeing he could do no more, the comedy director left 1219 and took the elevator back downstairs to find his friend Ira Fortlouis playing cards in the Frontier Room—and no worse for wear, despite Lowell Sherman’s ruse to get him out of the Arbuckle suite.

(msp. 97)

None of above solves the crime of another century. Too much of the original chronology has been spliced together and lost. There will be no director’s cut. That said, the unintended slapstick of the Arbuckle–Rappe tragedy still remains: Fred Fishback, by holding her up by the waist, by the ankles, and like a side of meat, started an iatrogenic catastrophe. Rather than restore her, Fishback unwittingly decanted more urine into her abdominal cavity from a ruptured bladder, which Virginia Rappe still suffered under Arbuckle’s watch.

There was no scapegoat for that initial injury and the prosecutors relied on this rather atomic fact.

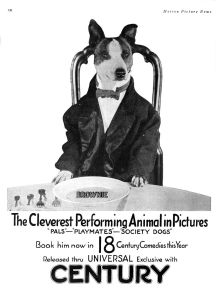

Fred Fishback, who served as Arbuckle’s dog on the stand, was a master at directing children and trained animals for Universal Pictures in the early 1920s.

[1] People vs. Arbuckle, Second Trial, “Testimony of Howard Vernon,” 2061. Vernon, a police department stenographer, transcribed the statement made by Fred Fishback on September 12, 1921.

This is all so fascinating. what is the timeline like for the book?

LikeLike

Also could you clarify a little bit on Lowell Sherman’s ruse?

LikeLike

It is fascinating. I have to slow down sometimes to think about everything so far written. Everything that happens in this tale resonates throughout the ms. When? Well, I still need a brave and generous publisher, preferably a university press, that will give me enough room for the whole picture, which is a kind of director’s cut. I have Rappe’s real background, Arbuckle’s sense of entitlement, and all these little stories about the lawyers, witnesses, and other stakeholders that says something about their honesty. I need an acquisitions editor who doesn’t think in terms of sales. That said, I am writing as if I could go to press next spring. We shall see, I have proposals out there.

LikeLike

This is fleshed out in the book. But Sherman had a certain disdain not only for Maude Delmont but the gown salesman, Ira Fortlouis. He was connected to Fred Fishback and arrived at the St. Francis with at least one sexual peccadillo that made him more interesting to me (aboard a steamer out of Portland, OR). Sherman did not want Fortlouis around when Rappe’s crisis in 1219 began. So, he told Fortlouis to scram because reporters were on the way up to talk to Arbuckle. I think Fortlouis was just an unwelcome presence and an unknown quantity who expressed too much interest in Rappe. His line of work, like Semnacher’s, was hiring women, too. He was really supposed to get lost at some point on his own. They had that in common, a business that could be repurposed for escorts. They even paired off at one point and likely knew each other beforehand. Fortlouis wanted to be part of Arbuckle’s Rat Pack and made it too obvious, I think.

LikeLike

Thank you! Was it Sherman who Maude Delmont was in the bathroom with when Virgina’s crisis began? She was wearing his pajamas, correct?

LikeLike