Toward the end of the third trial in late March 1922, Milton Cohen, one of Arbuckle’s five defense lawyers, cross-examined Kate Hardebeck at length. She was a rebuttal witness for the prosecution and had been Virginia Rappe’s longtime foster mother and housekeeper known as “Aunt Kitty.”

Cohen had a special place in Arbuckle’s defense. Not only was he the comedian’s personal lawyer, he had once been Rappe’s. He knew her, had been a friend. However, now that she was deceased and Arbuckle accused of having causing her death, Cohen was no longer bound by lawyer-client privilege. Thus far, he had used his personal knowledge of Rappe’s time in Los Angeles to procure witnesses who vouched for her alleged episodes of hysteria triggered by the smallest amounts of alcohol.

Cohen also knew that Rappe had left a paper trail over the years. She traveled a great deal and sent letters, postcards, and telegrams to not only the one foster mother, but the other who testified to Rappe’s good health and morals, namely Katherine Fox. Both women proved to be effective rebuttal witnesses, who painted a sympathetic portrait of their former charge. The prosecutors, especially Assistant District Attorney Milton U’Ren, wanted this idealized image of the victim preserved and to counter the “unfortunate” but fallen woman advanced by Arbuckle’s “million-dollar team” of lawyers.* So, the two foster mothers were undoubtedly encouraged not to mention any correspondence and stonewall where necessary, especially if that might intrude on the happy, girlish creature they described on the stand. And they may have done better than what was asked for. They told the defense lawyers that they had destroyed their foster daughter’s letters—this despite how precious she had been to them.

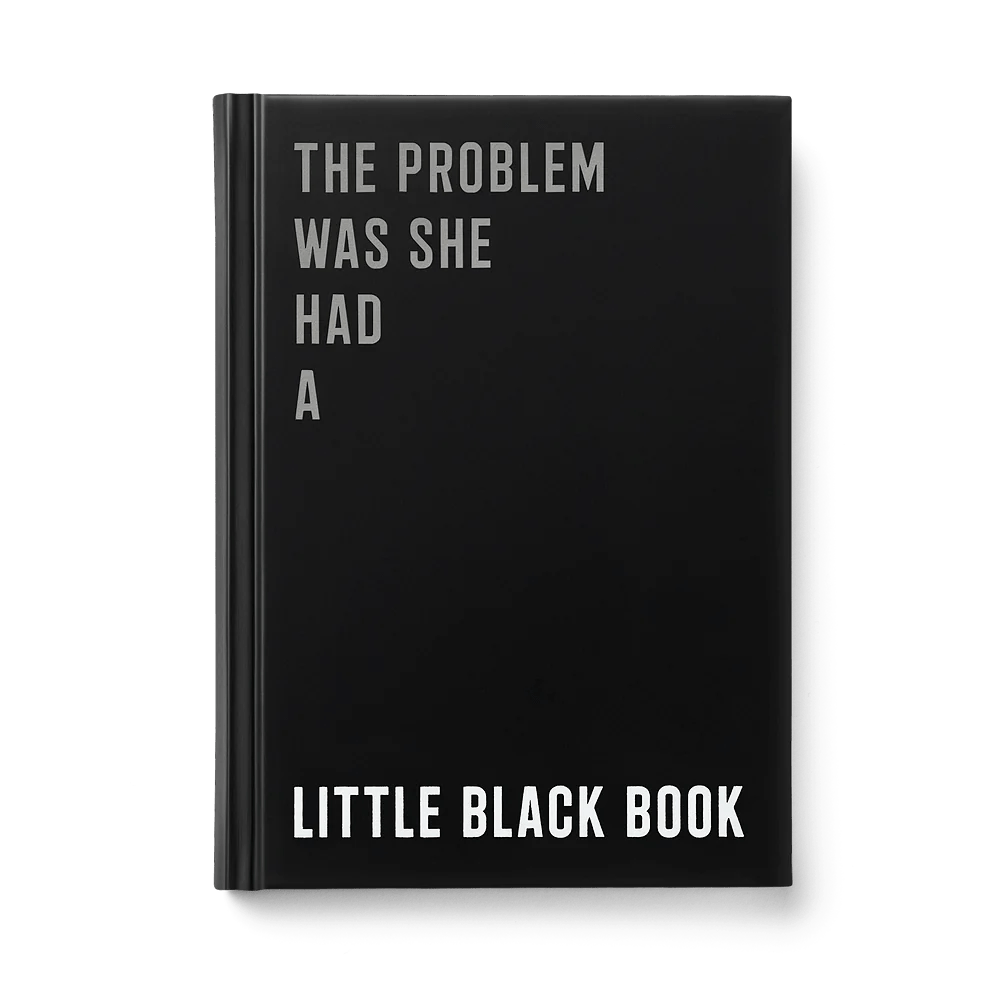

But one such document still existed. It lay on prosecution side of the shared consuls’ table. Cohen fixed on it. Was that the “diary” Al Semnacher, Rappe’s putative manager, had mentioned during his testimony a few days ago?

“Mr. U’Ren,” Cohen asked, “will you be good enough to let me have Miss Rappe’s diary?” Then Cohen turned to the witness. “By the way, did you deliver Miss Rappe’s diary to Mr. U’Ren.”

U’Ren started to object but Cohen cut him off. “I beg your pardon, just let her answer.” And Hardebeck answered in the negative.

When U’Ren handed the tiny book to Cohen, the latter saw that it wasn’t the diary. It had tabbed pages from A to Z. Nevertheless, he continued his fishing expedition.

COHEN: Q. Mrs. Hardebach (sic) have you ever see a book about six inches long by three inches wide, the sheets being gold edged?

A. No.

Q. And a black leather cover?

A. This is the book Miss Rappe had besides her address book, and we discarded that when we left Ivor Avenue, because it was full and had come apart.

Q. You say you discarded that book?

A. Miss Rappe discarded it before we left Ivor Avenue; and after that we had no telephone, and it was not necessary to keep the book.

Q. This is the only book, then, that you have?

A. Yes.

Aunt Kitty responded in a way that suggests there are two books: one for addresses, one for telephone numbers. While such items could be discrete objects in 1921, this didn’t sound convincing. So, Cohen continued to grill the witness. He needed a diary—or just a simple daybook, a proto-planner—with dates and jottings that might put Rappe where she had an episode, one that anticipated the fatal one ascribed to Arbuckle just two weeks before the Labor Day party of September 5, 1921.

In the end, Cohen let the matter go. U’Ren, however, did not. During the redirect examination, he took the precaution of burying the issue of a diary once and for all.

U’REN: Q. Mrs. Hardebach (sic) did Virginia Rappe keep a diary?

A. Not to my knowledge, no, I am sure she did not.

*In the revised narrative, a more accurate version will fall between these two contrived ones created for Arbuckle’s trials.